V Stock Study (6-29-23)

Posted by Mark on August 16, 2023 at 06:37 | Last modified: June 29, 2023 11:04I recently did a stock study on Visa Inc. (V) with a closing price of $227.96.

CFRA writes:

> Visa Inc. (V) operates the world’s largest retail electronic

> payments network, connecting consumers, businesses, banks,

> and governments in more than 200 countries and territories,

> enabling them to use digital currency instead of cash and

> checks. Visa’s core products include credit, debit, and prepaid

> cards, and related business services. Its processing

> infrastructure, VisaNet, processes approximately 637 million

> transactions per day. Visa’s customers include nearly 15,100

> financial institutions that issue Visa-branded products and

> nearly 80 million merchant locations. There are over 3.3

> billion Visa cards currently in circulation.

Over the past decade, this large-size company has grown sales and EPS at annualized rates of 10.4% and 15.9%, respectively. Lines are mostly up, straight, and parallel except for EPS dip in ’16 and sales + EPS dip in ’20. PTPM outpaces peer and industry averages while remaining relatively stable from 61.6% in ’13 to 61.9% in ’22 with a last-5-year mean of 63.7%.

Also over the past decade, ROE has been just ahead of peer and industry averages while increasing from 17.8% in ’13 to 45.3% in ’22 with a last-5-year mean of 37.8%. Debt-to-Capital has been less than peer and industry averages despite increasing from 0% in ’13-’15 to 38.7% in ’22 with a last-5-year mean of 35.9%. Interest Coverage is 35.5 and Quick Ratio is 1.1. M* gives a Standard rating for Capital Allocation and Value Line gives an A++ rating for Financial Strength.

With regard to sales growth:

- CNN Business projects 11.3% YOY and 11.2% per year for ’23 and ’22-’24 (based on 33 analysts).

- YF projects YOY 11.2% and 11.0% for ’23 and ’24, respectively (35 analysts).

- Zacks projects YOY 11.0% and 10.8% for ’23 and ’24, respectively (12).

- Value Line projects 9.2% annualized growth from ’22-’27.

- CFRA projects 9.2% YOY and 9.9% per year for ’23 and ’22-’24, respectively.

- M* gives a 2-year ACE of 11.2% annualized growth along with 10% per year x5 years in its analyst note.

I am forecasting just below the range at 9.0%.

With regard to EPS growth:

- CNN Business projects 14.7% YOY and 14.3% per year for ’23 and ’22-’24, respectively (based on 33 analysts), along with 5-year annualized growth of 16.5%.

- MarketWatch projects 14.9% per year for both ’22-’24 and ’22-’25 (39 analysts).

- Nasdaq.com projects 14.3% and 15.6% for ’23-’25 and ’23-’26 [14, 6, and 1 analyst(s) for ’23, ’25, and ’26].

- Seeking Alpha projects 4-year annualized growth of 15.3%.

- YF projects YOY 14.7% and 13.7% for ’23 and ’24, respectively (34), along with 5-year annualized growth of 14.7%.

- Zacks projects YOY 14.5% and 12.7% for ’23 and ’24, respectively (13), along with 5-year annualized growth of 15.2%.

- Value Line projects 10.6% annualized growth from ’22-’27.

- CFRA projects 14.8% for both ’23 YOY and per year from ’22-’24 along with a 3-year CAGR of 18.0%.

- M* projects long-term growth of 15.9%.

I am forecasting just below the long-term-estimate range (mean of six: 14.7%) at 10.0%. I am using ’22 EPS of $7.00/share as the initial value rather than ’23 Q2 EPS of $7.48 (annualized). FY ends Sep 30.

My Forecast High P/E is 29.0. Over the past decade, high P/E has increased from 26.5 in ’13 to 33.9 in ’22 with a last-5-year mean of 38.5. The last-5-year-mean average P/E is 32.3. I am forecasting toward the low end of the range [only ’13 and ’14 (27.3) are lower].

My Forecast Low P/E is 24.0. Over the past decade, low P/E has increased from 17.8 in ’13 to 26.2 in ’22 with a last-5-year mean of 26.2. The last-10-year median is 24.4. I am forecasting toward the lower end of range.

My Low Stock Price Forecast (LSPF) is the default value of $168.00 based on $7.00/share initial value. This is 26.3% less than the previous closing price and 3.8% less than the 52-week low.

Over the past decade, Payout Ratio has ranged from 17.4% in ’13 to 24.5% in ’20 with a last-5-year mean of 21.2%. I am forecasting below the entire range at 17.0%.

These inputs land V in the HOLD zone with a U/D ratio of 1.7. Total Annualized Return (TAR) is 8.2%.

PAR (using Forecast Average—not High—P/E) is 6.4%, which is less than I seek for a large-size stock. If a healthy margin of safety (MOS) anchors this study, then I can proceed based on TAR instead.

To assess MOS, I compare my inputs with those of Member Sentiment (MS). Based on 993 studies over the past 90 days (329 outliers and my study excluded), averages (lower of mean/median) for projected sales growth, EPS growth, Forecast High P/E, Forecast Low P/E, and Payout Ratio are 10.5%, 12.1%, 33.0, 25.1, and 21.2%, respectively. I am lower across the board. Value Line projects an average annual P/E of 28.0, which is lower than MS (29.1) and higher than mine (26.5).

MS high and low EPS are $13.10/share and $6.99/share vs. my $11.27 and $7.00. My high EPS is lower due to a lower forecast growth rate.

MS Low Stock Price Forecast of $175.00 implies a Forecast Low P/E of 25.0, which consistent with the above-stated 25.1. This is 4.2% above mine.

MOS seems healthy in the current study.

PEG ratio and Relative Value [(current P/E) / 5-year-mean average P/E] are other valuation metrics I have recently begun to monitor. Zacks reports PEG of 1.7 while my forecast EPS growth rate gives 2.8 (upper limit generally regarded to be 1.5). Relative Value (M* data) is 0.94.

Based on Kim Butcher’s “quick and dirty DCF” method, the stock should be valued at 24 * (13.10 – [2.80 + 0.6)] = $232.80.

I would look to re-evaluate this stock under $207/share [i.e. BUY zone tops out at $207; I then want to see an acceptable projected return in order to invest].

Categories: Uncategorized | Comments (0) | PermalinkRough Notes for Planning the Meetup (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on October 15, 2020 at 09:46 | Last modified: May 7, 2020 12:16Today concludes publication of some rough draft notes I had to complement this blog mini-series.

As I said last time, this may or may not be redundant information. More than anything else, I am trying to get more organized by clearing out my “drafts” folder.

———————————-

One step down from a qualifying interview would be to limit group openings. People sometimes have a fear of missing out. I could say “only 10 spots available.” I think this would likely attract people with a higher level of commitment, but my gut says it wouldn’t be as effective as a qualifying interview (assuming accuracy of screening).

What I don’t want to do is make the admissions criteria so stringent that nobody joins. I think this is also why I need to determine exactly what the group will focus on (i.e. collaborative research/programming/testing or teaching/trader literacy).

If the fees are mainly to establish accountability, then I could make them due up front and progressively refundable. Maybe the first meeting is free to explain objectives, future plans, and to collect money for those interested. I could then issue refunds at every meeting attended or to those who attend all meetings. I could also consider offering a discount to advanced traders with more to contribute.

One final possibility would be to advertise a pay it forward intent to discuss/teach something about which I am passionate rather than selling anything for a profit. This begs the question of if/when should education be free?

I feel strongly that unlike education in other domains, compensation should be given for teaching someone how to make money directly. Aside from how to operationally define “directly,” a big question mark surrounds the material itself. No guarantees can be made, and trading instructors are always potential charlatans presenting bogus information. Who should decide (and how) up front whether someone with something to teach is pure? That is a practical impossibility.

The caveat to my strong feeling, then, is justification because I know myself to be honest. One can never know that about anyone else. I may not even know that for myself because extraordinary future circumstances (Black Swans) can always arise.

Maybe this is why House says “everybody lies.”

The concept of abundance seems to be relevant here. The laws of abundance say “I can give to as many people within my reach; there is enough for everyone.” I’m not sure I buy into this. The likelihood that I and any retail investors with whom I ever associate will be enough to move the needle of the markets is supposedly slim. If word spreads, enough people learn, and everyone starts trading a particular way, though, then could Edge could be offset? There is no right answer.

Maybe I have a block with regard to a willingness to give. Heck, if organizations like TT* are out there disseminating free information to tens upon thousands of viewers then am I really worried about sharing what I know? I would have to believe in getting something out of it myself, too.

Who said I need to be the gatekeeper? Or is it me just trying to capitalize on the value of what I know (which I believe could be significant)?

I really don’t know.

* — Plenty of people are skeptical about TT teachings, however, which renders this comparison moot.

Categories: Uncategorized | Comments (0) | PermalinkRough Notes for Planning the Meetup (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on October 12, 2020 at 07:01 | Last modified: May 11, 2020 09:15Over a year ago, I did a blog mini-series on planning a Meetup group. In the next two posts, I just wanted to publish some rough notes to support that.

If you read the full mini-series, then you may find some of what follows to be overlapping and/or duplicate information. I had this saved in my “drafts” folder and in an effort to get more organized, I’m trying to clear those out by straight deletion or publication if I think some of the information might be new/different.

———————————-

Last time I described the Meetup I tried to organize and detailed its rejection. I can think of a few ways to proceed.

If I organize another Meetup group then I could charge a reasonable annual fee plus a fee per meeting. “Stiff,” not “reasonable,” may be a better description of $300 because I have never seen a Meetup charge $300 to join. Most groups don’t charge an annual fee at all and if they do, something like $10 seems more common. With regard to the meetings, $10 – $15 is about the maximum although I have seen some meetings packaged as educational programs that charge more.

Another possibility would be to charge the $300 annual fee while changing the group description. Previously, I said “the fee will be $300 for 12 group sessions.” I can see how that sounds like I am trying to market a service or product, which is why Meetup rejected it last time. Instead, I could still try $300 as the group fee and really emphasize the actionable material and potential value this group will provide in the group description. For example:

> Learning to trade has allowed me to feed myself for the last 10+ years,

> which is worth more than any educational content I have ever purchased.

I could state that while people of all levels are welcome, I seek commitment and emphasize a focus on accountability. Members can be held accountable for coming to sessions. Members can also be held accountable for participation although this may deter potential members who don’t feel confident in their knowledge and/or are scared to present for others. A softer requirement would be holding members accountable for making the effort to learn (operational definition?).

With all this focus on accountability, I probably don’t need to explicitly justify the annual fee. For people who trade, accountability is really important and very few roads lead there. I like this idea.

Especially in lieu of a stiff annual fee, I could require a qualifying interview to make the group more marketable. People are sometimes more motivated by a perceived barrier to entry—particularly if clearing the barrier results in an ego boost, which would be the case for more experienced traders. This would also raise the perceived competency level of the group. The downside would be losing potential members who know they are beginners and not yet ready.

Interviewing would also help me because I want people who will put in time and honor a commitment to the group.

I will conclude next time.

Categories: Uncategorized | Comments (0) | PermalinkDelving Further into TPAMs (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on June 11, 2020 at 11:28 | Last modified: May 11, 2020 13:41I’ve been going through my “drafts” folder this year trying to finish partially-written blog posts and get more organized.

TPAMs are Third Party Asset Managers. The August 2018 content below follows from Part 2.

—————————

In his article “The Coming Shakeout in Third-Party Asset Managers,” Greg Luken argues that TPAMs will face a leaner environment going forward. In order to survive, they will need to provide:

> A truly differentiated investment approach. In one of the most

> well-known studies of consumer behavior in America—the so-called

> “Jam Study”—two psychologists found that shoppers at a Bay-area

> grocery store were 10 times more likely to purchase one of the

> jams on display when the varieties of jam available were reduced

> from 24 to six.

>

> This pattern should be familiar to any advisor who has tried to

> parse through the vast number of available TPAM offerings on their

> broker/dealer’s platform lately. Past a certain point, adding more

> options to the menu does not benefit the advisor; it simply places

> another burden on their time in order to figure out the

> differences in the various choices.

>

> Going forward, TPAMs that are successful in defending their

> position on broker/dealer product platforms will be those that

> offer clearly differentiated investing approaches and results,

> not those whose portfolios boil down to minor variations on

> readily-available index funds, or a slightly different take on

> large cap growth.

This largely echoes my sentiment.

In addition to being truly differentiated, I believe TPAMs should be better. Perhaps Luken doesn’t address performance because it tends to be highly variable and never guaranteed (“past performance is no guarantee of future results”). Regardless, if the average bank product return is 2% and stocks on average have returned 8% per year then a professional delivering 6-7% per year is far better than the 2% people can achieve on their own. I believe, though, that being “professional” means they should do better than 8% per year.

My expectation for professionals to beat the market may be holding the bar too high. An internet search of “do professional traders beat the market” will turn up many articles arguing to the contrary. Over long periods of time, hedge funds certainly haven’t been able to do this. If beating the market is unlikely then perhaps “plain vanilla” will suffice especially if it consistently comes close to matching the market like passive index fund investing. Even this passive approach, which is exhaustively detailed in any Dummies Guide may be well worth the management fees.

It’s still hard for me not to expect something more. My last paragraph simply suggests realizing more is worth paying up for and if more isn’t delivered I probably won’t have to pay much (see fourth paragraph here).

Categories: Uncategorized | Comments (0) | PermalinkImplications of “No Fear Investing”

Posted by Mark on May 5, 2020 at 07:06 | Last modified: May 5, 2020 07:45Inspired by this, the current post completes a draft I started to write on July 6, 2014.

In the linked post, I asked the question: how can I possibly manage other people’s money during crazy market environments when I am so fear-stricken and on-edge for myself?

The difficulty of trading without fear is probably why so few succeed as full-time retail traders.

Only a couple ways exist to for me to live without fear and have skin in the game.

First, I have a full-time J-O-B that enables me to be adequately position-sized. The job prevents me from needing trading profits to pay living expenses every month. My level of fear is therefore decreased because even when the market goes sour, I still have my J-O-B to pay the bills.

Second, my level of wealth may afford me to cover living expenses by putting a “small” fraction at risk in the market. Little at risk means no, or little fear.

Malcolm Gladwell writes about why the first case is hard to navigate. Gladwell writes the key to success in any particular field is a matter of practicing the specific task for 10,000 hours. I would have a hard time getting to 10,000 hours as a part-time investor, which means I may never make a whole lot in the markets because I’ll never be invested large. Thank goodness for the J-O-B. This circular reasoning pretty much eliminates the possibility of full-time trading.

The second case is difficult for two reasons. First, I believe this requires [multi-] millionaire status, which only accounts for a small percentage of the population. Most traders aspire to be millionaires but are not and are therefore unable to get away with risking a little. Second, if I were a millionaire then I would have to be content making only enough to cover living expenses. Many people with lots of money aim to make lots more. A business owner may want to buy/run more businesses or locations, for example. Doing this in the financial markets means putting more wealth at risk, which opens the door to fear when the market environment goes ballistic (e.g. March 2020).

Categories: Uncategorized | Comments (0) | PermalinkEnvestnet Case Study (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on March 23, 2020 at 11:51 | Last modified: May 11, 2020 12:03Continuing on with my year-long organization project, this is an unfinished draft from August 2018 on performance.

I was confused about many things from this draft, which is now a completed post. I have figured it out; it was in reference to this Envestnet study. Part 1 was in May, Part 2 was three months later, and part three is seen below.

—————————

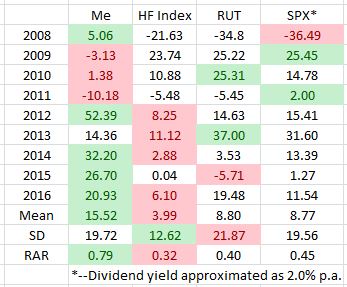

Kudos to Envestnet for outperforming the index (table from second link above). Furthermore, I only edged out Envestnet by 79 basis points when normalized for standard deviation (SD). As discussed in the first link above, however, because upside SD doesn’t hurt anyone I actually outperformed them by over 9% per year. This is a different perspective that leads to completely different conclusions.

My belief (based on a sample size of zero) has been that hedge fund (HF) managers and those who develop trading strategies for these funds are people like myself. I would think these are people who have studied and read everything they could find in the process of learning how to trade. I would think they are well-versed in system development and statistical fundamentals. I would also think they are well-schooled in quantitative analysis and the art of coding.

With that said, the HF performance is extremely interesting to me because hedge funds seem to significantly underperform:

The name suggests HFs aim to limit losses by hedging, which suggests a lower SD. They do, in fact, win the SD category. Because hedges generally cost money, I would not expect them to generate the highest absolute returns. Also in their defense, perhaps, is the fact that from 2008 – 2016 the market has been mostly up, which may not be where they excel since hedges are not needed.

I still find it hard to accept significant HF underperformance, though. From 2008 – 2016 HFs got trounced in mean return. Even on a risk-adjusted basis, the worst-performing index (RUT) beat them by over 20% and my 0.79 beat them by 146% over those nine years! For a 2/20 (or even 1/10) fee structure, I just don’t see how the value proposition exists.

Or maybe this is substantiation that I am just that good? Perhaps I am, indeed, professional trader (TPAM) material.

Categories: Uncategorized | Comments (0) | PermalinkEnamored with Day Trading? (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on March 5, 2020 at 10:32 | Last modified: May 4, 2020 12:11Today I will finish up the last post by getting into some actual data about day traders.

Chague et al. tracked 19,646 day traders from 2013 through 2015. This study received lots of buzz in Brazil. In addition to being extremely popular, day trading is also very controversial there.

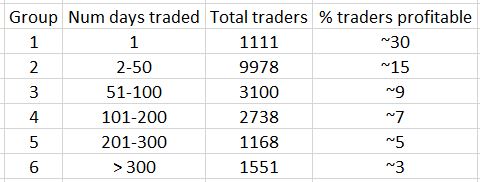

The results boiled down as follows:

These data suggest day trading and casino roulette share similar odds of winning. The more people day trade, the better the chance they have to lose everything.

Chague et al. explain the results run contrary to self-selection. In self-selection, individuals with better performance generally persist in an activity. This is common in activities that exhibit “learning by doing.” Michael Mauboussin, in The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing (2012), agrees: practice does not make perfect when the outcome is due to luck rather than skill.

Trading educators want us to believe something altogether different. I often see [day] trading advertised as a craft to be developed over time. I won’t be overnight sensation. It takes hard work. The more I practice, the more classes I take, the more mentoring sessions, the more I spend on this education, the more I will succeed. In the current study, empirical data along with statistical regression analysis showed performance to be deficient with those trading longer faring even worse.

Despite the poor averages, perhaps those who end up in the green are a smashing success. Looking at the 47 out of 1,551 day traders who were profitable after 300 days:

- Only 17 earned more than the Brazilian minimum wage (16 USD/day)

- Only eight earned more than an newbie Brazilian bank teller (54 USD/day)

- One earned 310 USD/day

For all the stress and strain of day trading, the chance of making a respectable $78,000/year was 0.06% and the chance of making more than an entry-level bank teller wage ($13,608) was 0.5%. No windfall profits were to be found with tiny profits few and far between. The average daily result was a loss of $49.

Even to realize the entry-level bank teller wage, one had to endure a large variability of returns. For the eight mentioned above, the daily profit ranged from $632 to $3308. In other words, that $54 average profit/day was usually between -$578 to +$686 per day for the most consistent and -$3254 to +$3362/day for the most volatile. Sleepless nights, anyone?

If the outlook isn’t bleak enough already, Chague et al. explain why their study is likely to overestimate actual performance. First, income taxes and other relevant expenses (e.g. trading platform cost, courses) were not included. Second, only days where total contracts bought equaled total contracts sold were included. They cite a study by Juhani Linnainmaa (University of California at Berkeley, 2005) that says retail day traders are reluctant to close losers (called the “disposition effect”). Days with unequal numbers of contracts bought versus sold were likely losers, therefore. By not including these in this study the abysmal reported day trading performance is, itself, artificially inflated.

Chague et al. conclude “it is virtually impossible for an individual to day trade for a living, contrary to what the brokerage specialists and course providers often claim.”

This is certainly something to think about!

Categories: Uncategorized | Comments (0) | PermalinkEnamored with Day Trading? (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on March 2, 2020 at 10:34 | Last modified: May 4, 2020 11:19The next two posts are an absolute must-read if you have any interest in day trading for a living (second-to-last paragraph).

As I have discussed many times, data is the financial industry is frequently absent. This blog mini-series focused on the lack of performance reporting. This post focused on the lack of evidence to support technical analysis.

Now we have some actual data!

Today’s post is based on “Day Trading for a Living”: an August 2019 article by Fernando Chague, Rodrigo De-Losso, and Bruno Cara Giovannetti out of the University of São Paolo in Brazil. I encourage you to take a look at the full manuscript.

Chague et al. talk about the lack of quality data about the odds faced by people who choose to try their hand at full-time day trading. The few studies that exist do not focus on individuals who trade regularly, which “largely overstimates the odds” of having success. Second, the few studies that exist do not follow individuals from their first trade, which makes it difficult to understand whether learning is possible in this domain. Finally, the few studies that do exist sample periods that predate the modern-day trading landscape, which includes “fierce competition of algorithms and high-frequency traders.”

Futures trading in Brazil is very popular. Chague et al. cite a 2018 report from the Futures Industry Association stating annual volume of the mini-Ibovespa futures totaled 706 million contracts: much greater than the E-mini S&P 500 Futures (445 million contracts) and S&P 500 Index Options (371 million contracts). Futures and options trading volume of the Brazilian Exchange ranked third worldwide (2.57 billion contracts). The population of Brazil is approximately 40% that of the USA.

This is basically to say that day trading in Brazil is virtually a national pastime—much more popular than in the United States.

The Brazilian futures industry is similar to the USA. On one [large] side of the spectrum are the social media day trading “gurus,” vendors selling day trading systems, and lots of [supposedly?] profitable indicators/newsletters for sale. These are entities that have been presumably advertising and profiting throughout the industry for years. On the other [tiny] end of the spectrum are economists, social scientists, and data scientists.

Remember this excerpt?

> The oft-quoted statistic that 90% fail within five [1-2?]

> years supports this. I don’t know who [if?] did the original

> study but it is consistent with what I’ve seen of human

> nature from attending trading groups.

The time has finally arrived to see how this shakes out by putting some actual context behind it.

Categories: Uncategorized | Comments (0) | PermalinkMore About KD (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on December 30, 2019 at 13:27 | Last modified: April 24, 2020 14:53Today I will conclude my complete detailing of KD (not Kevin Durant).

KD has an interesting business model that compliments his personal agenda quite well. As mentioned in this third paragraph, developing trading systems is hard. If you purchase his product, then you are eligible to participate in his program. The program collects viable trading strategies that satisfy his system criteria. If you submit a viable strategy that is subsequently profitable over the following six months, then he will give you at least one (sometimes more) passing strategies (e.g. from other customers) from the same or different month in return. With this business model, his own customers feed him viable strategies! This clearly augments his personal agenda as a full-time trader. The program also serves as a productivity multiplier for his customers; for the time it takes to develop one passing strategy, more will be returned.

I cannot recommend you train under KD for one and only one reason: I have not yet had success finding any viable strategies. I mentioned the “specter of scam” in the fourth paragraph here. In case you haven’t looked around lately, fraudulent sales pitches abound in the financial industry. I have written about CNBC’s American Greed (e.g. here and here). I’ve also posted on misconduct in the financial industry. I have to wonder whether KD is bogus, too (and he would want me to based on the 5-part mini course discussed last time). It wouldn’t be the first time a nice personality has engaged in criminal behavior.

The possibility also exists that what KD teaches doesn’t work for the vast majority of his customers. If this is true, then whether he has an ethical obligation to disclose while marketing his wares is a matter for debate.

KD rates well on one particular website that focuses on trader education programs. This site appears to review nearly 300 different education programs (and services). The founder claims to be a once-upon-a-time charlatan who did cold calling sales to swindle investors. He claims to have spent nearly three years in prison for these efforts and has since become one of the “good guys” who knows fraud, Ponzis, and optionScam.com when he sees it.

Interestingly, about the only positive review I can find on this site focuses on KD. A couple public comments linked to that review suggest KD owns the site. I can’t imagine KD would have time to do all the reviews on that site, maintain the entirety of his online presence, and trade for a living. No way.

I suppose he could be delegating responsibility to an entire team, though. Hmmm…

Categories: Uncategorized | Comments (0) | PermalinkMore about KD (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on December 27, 2019 at 07:16 | Last modified: April 24, 2020 14:14I wanted to go into a bit more detail about the guy I discussed here.

It’s not Kevin Durant.

KD is a vendor of trader education. Beware vendors and the inherent conflicts of interest that accompany them. The red flags should fly when I encounter people who have something to sell. I should be knowledgeable about frauds, scams, and claims: some of which have been subjects for this blog (e.g. here, here, and here).

Like some vendors, KD has his own piece to share on steering clear of snake oil salespeople. As clickbait, he offers a free 5-part mini course on due diligence for trading educators. Writing such a piece is good marketing because third person language (it/they) naturally sets himself off from what he is writing about. That is to suggest “I am not one of them.”

KD’s claim to fame is posting taking first place in the 2006 World Cup of Futures Trading Championships in the midst of three consecutive years of 100%+ returns. He was later profiled as a “market master” in The Universal Principles of Successful Trading by Brent Penfold (2010).

Part of enjoying success as a guru or trading educator is perfecting the online marketing piece, which KD has certainly done. I first encountered him as a guest contributor on the System Trader Success blog. He moderates an algorithmic trading contest on the Big Mike Trading website (now futures.io). He was a frequent contributor to SFO, and Active Trader magazines (no longer in existence) along with Futures magazine (still running). He has written at least one print book—Building Winning Algorithmic Trading Systems—along with multiple e-books that he generously circulates. I’ve seen KD post on at least two popular investment/trading forums. He has a number of videos on YouTube. He often does webinars from his home and you can watch him speak with kindness and humility.

As a further way to establish a presence and boost his reputation, KD often posts online responses to negative reviews. Personally, I grow more suspicious when I see responses to negative comments. On its own, I may or may not believe a negative review since many are fake (see second-to-last paragraph). When the subject of the review appears defensive, then I suspect the allegation to be more authentic. I’m guessing KD disagrees else he wouldn’t do this.

KD answers questions online, which is a shining star, and he is really good answering questions via e-mail. I have e-mailed him numerous times. He is a prompt responder. He never responds with any frustration, and he addresses all questions.

One of KD’s common responses to my questions is “there is no right or wrong answer.” I find this to be an interesting phenomenon that I will revisit at a later time.

Categories: Uncategorized | Comments (0) | Permalink