Investing in T-bills (Part 17)

Posted by Mark on March 23, 2024 at 08:51 | Last modified: April 10, 2024 09:26Higher initial/maintenance margin requirements is one reason why option traders may choose [taxable] T-bills [interest] over tax-exempt munis. Another reason to favor T-bills is the muni bond de minimis rule.

I want to clarify interest on zero-coupon T-bills as discussed in the third-to-last full paragraph of Part 16. These are taxed as if interest income were being received even though no income is actually received until the bond matures. Whether price appreciation to par or a semi-annual coupon payment, both are taxable interest as far as Uncle Sam is concerned.

As far as munis (issued by state, city, and local governments) go, interest is generally free from federal taxes and is:

- Usually free from state tax in the state of issuance.

- Not taxed by some states regardless of the state of issuance.

- Sometimes exempt from state tax at the time of issuance by that same state even when said state usually taxes them.

Unlike muni interest, bond price appreciation is usually taxed in accordance with the de minimis rule. At issue is whether price appreciation will be taxed as ordinary income or as capital gains. This is done as follows:

- Multiply the face value by 0.25%.

- Multiply that result by number of full years between bond purchase and maturity date to get de minimis discount.

- Subtract de minimis discount from muni par value to get the minimum purchase price.

- If actual purchase price is less (equal to or greater) than the minimum purchase price, price appreciation on the bond is subject to ordinary income (capital gains) tax rates.

For example, imagine $97.75 purchase of 10-year muni paying 4.00% APY with par value of $99 and six years until maturity.

De minimis discount = $99 x (0.25% / 100) x 6 = $1.485

Minimum purchase price = $99 – $1.485 = $97.515

Because $97.75 > $97.515, price appreciation will be taxed as capital gains. If held for over one year (one year or less), then capital gains tax rates are lower than (equal to) ordinary income tax rates.

The de minimis risk [of having to pay ordinary tax rates on price appreciation] is greater in rising interest rate environments. Since interest rates are inversely proportional to bond prices, increasing rates are associated with decreased bond prices.

One case where price appreciation may be tax-exempt is a zero-coupon municipal bond. These are always bought at a discount since they make no interest/coupon payments and price appreciation to par value is usually not taxed. The biggest caveat seems to be selling before the maturity date. In this instance, any price change realized on zero-coupon munis will be treated as a [short- or long-term depending on holding period] capital gain or loss.

Is that light at the end of the tunnel I see?

I will continue next time.

* — The Part 11 disclaimer applies: please consult a tax advisor for the definitive word on these matters.

Investing in T-bills (Part 16)

Posted by Mark on March 22, 2024 at 09:43 | Last modified: April 10, 2024 09:46Last time, I began to explore the idea of trading options on top of tax-exempt munis since interest on T-bills is taxed at the Federal level. Today I continue the discussion with regard to maintenance margin requirements.

Let’s define two new terms: initial margin and maintenance margin. Initial margin is the percent of purchase price that must be paid with cash in a margin account. Maintenance margin, currently set at 25% of the total securities value per Financial Industry Regulatory Authority requirements, is the amount of equity that must be kept in the margin account going forward.

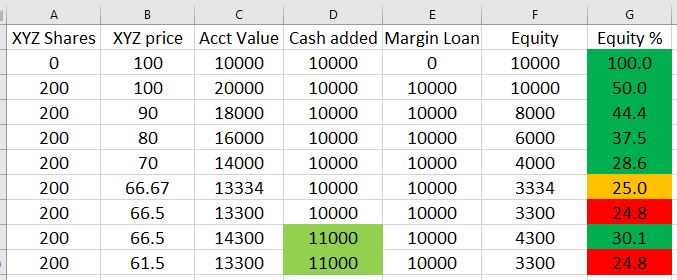

Maintenance margin for equities is best illustrated by a table:

- A margin account is opened by depositing $10,000 (column D).

- Using the $10,000 free cash and $10,000 borrowed from the brokerage (column E), 200 shares of XYZ are purchased at $100/share causing an equity percentage [col G = 100 * (col C – col E) / col C] drop to 50%.

- Equity percentage drops further as the share price drops.

- When XYZ hits $66.67/share, equity percentage is at the minimal threshold of 25%.

- At $66.50/share (a drop of 33.5% from initial purchase price), equity percentage is below threshold. Brokerage will issue a margin call forcing deposit of more cash or securities to avoid sale of XYZ at a big loss.

- Depositing an additional $1,000 (now $11,000 total in column D) restores equity percentage (30.1%) above the minimum threshold where it will remain unless XYZ drops to $61.50/share resulting in a subsequent margin call.

Although taxable, T-bill interest qualifies for 1% initial and maintenance margin for maturities up to six months. This means $100,000 of T-bills may be purchased while preserving $99,000 for option trading. Beware, though! This defines how much capital may be borrowed rather than how much should be invested. As stated in this third paragraph, capital should never be borrowed to invest in T-bills. T-bill investments count 100% against the cash balance* and margin loans begin if cash balance drops below zero (hence the 10% cash buffer mentioned in this second-to-last paragraph).

For the sake of option trading, low maintenance T-bill margin seems like a great deal that is actually just a necessary precaution (see bottom of Part 8) to prevent the brokerage from pocketing additional interest. While the customer gets paid 0.35% on free cash, the brokerage could invest that cash in T-bills to make 5% or more. I need to do more research to determine if this actually happens, but it seems plausible since T-bills are about as safe as any investment can get.

Disadvantaged margining for munis likely offsets their tax-exempt benefit. At my brokerage, initial and maintenance margin are the greater of 20% of the market value or 7% of the face value. I see another brokerage listing maintenance margin at 25% of bond market value (and initial at maintenance margin x 1.25). Either way, munis eat up at least 20x more in buying power than T-bills making them more likely to hamper option trading.

Next time we will study de minimis.

* — In contrast to naked puts that, as discussed in this last full paragraph, raise cash balance.

Investing in T-bills (Part 15)

Posted by Mark on March 20, 2024 at 09:41 | Last modified: April 7, 2024 10:46The meandering mini-series continues with some further comments about taxes and municipal bonds.

As a sidebar to what seems like a series of sidebars, meandering is not a bad thing with these blog posts. What ends up presenting is the opportunity to touch on a number of related subjects. Researching and writing about these topics helps me learn. Hopefully you can gain something too in the form of some well-rounded financial understanding.

Because T-bills (along with all Treasury bonds) are subject to Federal tax [exempt from state and local taxes], I often see the recommendation to hold them in tax-advantaged retirement accounts such as traditional or Roth IRAs. Traditional IRAs owe tax on bond interest only when funds are distributed (withdrawn) rather than as interest is earned. This allows for longer compounding. Roth IRA contributions are fully taxed up front allowing bond interest to be effectively tax-exempt.

Retirement accounts must be cash accounts. Cash accounts are not eligible for margin loans from the brokerage (“trading on margin”). Neither are cash accounts subject to initial and maintenance margin requirements* that enable certain types of option trading such as call writes and short puts.

To me, the cash-versus-margin-account delineation clarifies the bond recommendation from above. Fixed income (i.e. T-bills or other bonds) may be managed as one asset in a diversified portfolio (e.g. an allocation made up of 50% large-cap stocks, 20% small-cap stocks, and 30% fixed income) for which a cash account like an IRA is perfectly suitable. If using T-bills to maximize return on cash left over from option trades, however, then T-bills and options must be in the same account: likely a [option-enabled] margin account rather than an IRA (cash account). The above recommendation would not apply.

With tax on T-bill interest weakening the case for trading synthetic long stock + T-bills in lieu of long shares,** municipal bonds come to mind. “Munis” (municipal bonds) are tax-exempt. They are generally a better choice for higher tax brackets because the amount saved by not owing tax on bond interest taxed is greater. When comparing munis with other bonds, a “tax-equivalent yield” (TEV) is often calculated: TEV = muni yield / (1 – marginal tax rate***).

Given the T-bill from Part 12 paying 5.355% YTM, would a muni paying a 3.8% coupon be a better choice? Assuming a 24% tax bracket (marginal tax rate), the muni:

TEV = 3.800% / (1 – (24 / 100)) = 5.000%

All else remaining equal, in this case T-bill is the better way to go.

I will continue next time.

* — To be addressed later

** — Recall this comparison was the real purpose of the entire mini-series. As discussed in

the first paragraph of Part 11, I got my answer early.

*** — Marginal tax rate is the percentage at which my last dollar of taxable income is taxed.

Investing in T-bills (Part 14)

Posted by Mark on March 19, 2024 at 08:58 | Last modified: April 7, 2024 10:46In the fourth paragraph of Part 12, I mentioned creation of a bond (T-bill) ladder without explaining the what or why.

Bond laddering involves buying bonds with different maturity dates thereby enabling the investor to respond relatively quickly to interest rate changes. Investing in bonds maturing on the same date carries high reinvestment risk: being forced to roll over a large capital allocation of maturing bonds into similar fixed-income products with a much lower interest rate. The ladder therefore facilitates a steadier stream of cash flows throughout.

Reducing reinvestment risk and smoothing out interest payments is of limited importance to me since my T-bills mature within months. The Fed usually decides whether to raise/lower interest rates during its eight scheduled meetings per year (and rarely by more than 50 basis points at a time). Over 3-4 months, drastic interest rate changes have seldom been seen. T-notes (T-bonds) mature in 2-10 (20-30) years—periods of time over which large rate changes are more likely.

Limiting price risk is another benefit of bond laddering that doesn’t apply much to my short-dated T-bills. When interest rates rise, bond prices fall; this affects longer-dated more than shorter-dated bonds.* A worst-case scenario would be large portfolio allocation to long-dated bonds at the unexpected start of a rising interest rate environment followed by a catastrophic life emergency forcing bond sale at a substantially lower price to raise cash. Contrast this with an initial outlay of five equal tranches of capital to bonds maturing in 2, 6, 10, 20, and 30 years. The rising interest rates would not hurt the 2-, 6-, and 10-year T-notes nearly as much as the 30-year T-bonds.

One final benefit to bond laddering is liquidity improvement [of a fixed-income portfolio]. Although Treasurys tend to trade on a relatively liquid secondary market, bonds by their nature are not generally liquid investments and cannot be cashed in anytime without penalty. In the example just given, 20% of the total allocation matures after 2, 6, 10, 20, and 30 years making cash available in a relatively short period rather than having to wait 30 years for any (all) of it.

Liquidity improvement is the main reason I use a bond ladder. Should the stock market move sharply against me, I may need cash to close losing positions. Every week I get a cash-balance infusion when T-bills mature. Rather than reinvest, I can skip a T-bill purchase(s) and use the cash to manage option positions. In combination with the 10% cash buffer (see last two full paragraphs of Part 13), I will hopefully avoid having to borrow funds from my brokerage and paying high margin interest.

I will continue next time.

* — Duration is a bond’s change in price per 1% increase in rates.

Investing in T-bills (Part 13)

Posted by Mark on March 11, 2024 at 11:25 | Last modified: April 6, 2024 09:52Last time, I discussed how I invest in zero-coupon T-bills and presented a sample calculation of annual yield. For educational purposes, I will begin today’s post with a similar calculation for a T-bill with coupon.

I have previously invested in couponed T-bills but will no longer be doing so. I recently spoke with a fixed-income representative at my brokerage who told me YTM is calculated a bit differently and for more complexity because coupon payment(s) and accrued interest need to be factored in, the payout ends up being slightly less for numerous couponed T-bills versus zero-coupon T-bills she has compared.

As a sample calculation, consider a T-bill purchased for $99.079 (10X multiplier applies) on Mar 19, 2024, to mature on Aug 31, 2024 (165 days). This was stated to have a 5.357% YTM with $1.766 accrued interest (first coupon Feb 28, 2023) and 3.25% coupon. The 3.25% coupon is semi-annual with each coupon payment half that amount. This bond, therefore, issued coupon payments on Feb 28 and Aug 28, 2023 (or the first business day thereafter if on a weekend), along with Feb 28, 2024. Accrued interest—which gets subtracted since owed to previous bond owner—is from the latter date, and a final coupon payment (Aug 28, 2024) will be issued at [first business day after if on a weekend] maturity:

100% * ((1000.00 – (99.079 * 10)) + (1000 * (3.25 / 100 / 2)) – 1.766) / (1000 * (165 / 365)) = 5.241%

As with the zero-coupon T-bill calculation, this is not an exact match (to 5.357%) but in the ballpark. As a partial explanation, the fixed-income representative told me something about the YTM calculation for couponed T-bills not accounting for accrued interest that must be repaid and is not actually part of the calculation.

I always maintain a cash buffer when investing in T-bills. I hinted at this in the second-to-last paragraph of Part 4 as well as Part 12 where I mention the 90% number. If the market moves against me and a short option need to be bought back for a loss, then my cash balance will go down. If I am consistently buying long options that don’t pay out then cash balance can be depleted as well. As stated in the third paragraphs of Part 2 and Part 3, the last thing I want is for my cash balance to go negative and be forced to borrow brokerage funds because the margin interest rate is over double what I receive on T-bills.

Were I primarily investing in long stock, a cash buffer would be less important. Losing $5,000 on a $20,000 stock position would likely be followed with investment of the remaining $15,000 in a different stock; only if I turned around and invested another $20,000 would I deplete the cash balance. Besides, as mentioned in the fourth paragraph of Part 2, a [predominantly] stock investor will use most free cash for equity investments thereby leaving little left over for T-bills anyway.

I will continue next time.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | PermalinkInvesting in T-bills (Part 12)

Posted by Mark on March 7, 2024 at 08:43 | Last modified: April 6, 2024 09:13As mentioned in the fifth-to-last paragraph of Part 8, if trading options with a lot of free cash in the account then one really must invest that cash in T-bills (or some comparable bond position).

My goal with T-bill investment is to earn a relatively high interest rate as discussed in the second paragraph of Part 2. I do not claim this to be optimized or any sort of “best” approach. It makes sense to me, it fits my risk tolerance, and it accomplishes the goal pretty well. The process is a mechanical one that—as mentioned in the fourth paragraph of Part 2—does require a minimal time commitment (usually up to 10 minutes per week).

See Part 1 for a refresher on T-bills.

I allocate about 90% of my free cash to a bond ladder with 6-10 tranches. Every Tuesday, I use my brokerage platform (secondary market) to filter for Treasurys up to one year to maturity, to sort by yield-to-maturity (YTM), and to find highest YTM with shortest maturity date. I generally target maturities 6-10 weeks out and see YTM proportional to [weeks to] maturity. If I see a higher yield for a much shorter maturity date, then I pounce (it may not be the good deal it seems; I don’t yet know what mitigating factors play into this phenomenon). This may result in multiple tranches maturing on the same day that I can later smooth out by purchasing two tranches maturing one week apart on the same day.

Once I have a CUSIP number for the desired T-bill, I call the brokerage to place the order. Prices quoted over the phone are sometimes [slightly] lower, which means a higher YTM. No additional fee is assessed for placing the order by phone and when I call earlier in the day, I usually get connected within 2-3 minutes.

I present one example of a recently-purchased T-bill for those who may want to do the same to ensure accuracy or investment understanding. On Feb 27, 2024, I purchased a T-bill for $99.202 maturing on Apr 23, 2024, and paying 5.355% YTM. Yield is an annualized number that requires division by fractional holding period (in this case 56 days). Also, a 10X price multiplier is always involved. The calculation is:

100% * (1000.00 – (99.202 * 10)) / (1000 * (56 / 365)) = 5.201%

This is not an exact match but in the ballpark. A fixed-income representative recently told me T-bill YTM calculations factor in TVM. I don’t know exactly how the fudge factor works, but approximate is all I need (and far better than 0.35% or 0.57%).

I will illustrate a T-bill with coupon next time.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | PermalinkWhat Percentage of New Traders Fail? (Part 6)

Posted by Mark on August 6, 2020 at 06:28 | Last modified: May 17, 2020 14:27Today I conclude with excerpts from a 2013 Forex website forum discussion. The initial post, which tries to rebuke traditional wisdom, is Post #1 here. Forum content is unscientific and open to scrutiny. Do your own due diligence and buyer beware.

—————————

• Post #54, Set:

> Trading is just like learning any other skill. The catch

> is that people often learn trading with minimal supervision

> and guidance. This is what discourages most people.

>

> But we can change this around. As trader gets more involved

> and contribute to a community, he will have more

> encouragement to work through the learning curve. Recently,

> I have decided to contribute daily to this forum and I have

> noticed a significant change in my attitude towards trading.

>

> Trading is a business and Henry Ford once said, “a business

> that makes nothing but money is a poor business.”

>

> I really like this forum because of all the great mentors

> available here and I aim to become one myself.

I like the positivity here as opposed to the oft-seen flaming, ego, and negativity I see in trading-related forums. I definitely think we must be selective in what we accept, but I think a general belief that people are good can help the foundation.

• Post #56, Big

> Yes, it is skewed and does not relate to the statement

> that 99%, 95% or [insert here any anecdotal % that you

> extract from your nether orifice here, because no one

> that makes the statement has the figures anyway]…

>

> Let’s assume that we start from day 1 and we’ll use

> 95% because, well, why not!

>

> Year 1: 95% newbies fail 5% succeed

> Year 2: 95% fail 5% succeed, + the 5% that succeeded

> last year are still hanging around because they wouldn’t

> quit when they are profitable.

> Year 3: 95% of newbies fail and the successful 5% of

> newbies join the profitable dudes from year 1 and 2.

>

> Get it? Many of the unsuccessful traders will quit, but

> the successful traders will stay on so the percentage of

> profitable traders grows each year… it is cumulative!

>

> The “profitable” percentage in the brokers’ reports show

> the experienced traders that have been here for years, in

> addition to the small percentage of newbies that have been

> profitable. It will always grow because you don’t quit if

> you are profitable.

>

> Most unprofitable traders, if they do not become

> profitable, will eventually quit so that number is more

> likely to level out.

>

> I’d like to see the yearly figures of newbies after one

> year, two years, three years, etc… because it may take

> several years to become successful. That, and only that,

> would test the validity of the anecdote that 95 – 99% fail.

This is a really good example of how such broker numbers can be skewed to the upside. I also remember back to Post #33 where successful traders having multiple accounts was discussed.

• Post #62, Unk

> The percentage of traders that fail are much higher than

> the statistics show. Of all the traders that show a positive

> equity curve most still fail as the few pennies they

> make won’t even beat a McD wage. If you make some rules

> on what is actually “profitable” e.g. making a living

> off it / competitive salary (with benefits, etc.) than the

> field of successful traders gets much slimmer…

The Brazilian day-trading study agrees with this.

• Post #64, Pip

> The percentages are so high because it’s calculated per

> quarter. It’s not because “winning traders” stack up each

> year: some winning traders quit and many losing traders

> don’t. The chance for having a significant amount of

> winners in a quarter is very large. The fact that these

> numbers are so skewed toward losing is proof that of few

> profitable traders. There’s a very big chance for any loser

> to be profitable over one month or year. So Guy 1 loses

> $2K in three months and Guy 2 wins $1K. Next quarter

> Guy 1 wins $1K in three months and Guy 2 loses $2K.

> Both are losers, yet the statistics say there’s one loser

> and one winner in each quarter.

This seems like another interesting example to illustrate how success statistics may be biased to the upside. Losing traders will have to quit, though, if they lose too much or go bust altogether.

Brokerages certainly have an underlying motive to portray success. If the general public believes many retail traders succeed, then newbies will be more likely to try themselves. The more people trade, the more money brokerages make.

This thread has provided us with lots of good fodder for critical thinking and evaluation.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | PermalinkWhat Percentage of New Traders Fail? (Part 5)

Posted by Mark on July 14, 2020 at 06:13 | Last modified: May 17, 2020 13:14Today I continue with excerpts from a Forex website forum discussion in 2013. The initial post, which tries to rebuke traditional wisdom, is Post #1 here. Forum content is unscientific and open to scrutiny. Do your own due diligence and buyer beware.

—————————

• Post #47, 4xp

> The simple fact is that more traders have to lose than win

> in order for the winners to make money… we are able to

> have leverage because of so many losers in the market.

> IMO, I believe the number is closer to 90% failure rate

> than 99% that many have already espoused.

>

> The reason forums like this one are so popular is because

> there are so many losers. Most people are not making any

> money trading, so they come here looking for and hoping to

> find something they can learn from. By the time you get

> here, you have the blind leading the blind. Many admit

> they are newbies or learning. Others want to pose as

> experienced traders because of an oversize ego, but they

> are really losers. Others come here because they have a

> web site, but they do not know how to trade, so they

> beguile newbies to head to their site. When it is all said

> said and done, it can be hard to discern the very few that

> are good traders because they are hiding behind the guise

> of their computer screen.

>

> When someone says you cannot beat the market, that is all

> rubbish. The reason the ~10% beat the markets is they are

> armed with and trade their methodology so they can beat

> the markets. The few that win consistently take personal

> responsibility for their actions rather than blaming the

> markets. The markets can only go up or down. You just

> have to have a methodology that discerns which direction

> it is going then jump on board.

>

> It is also no such thing that the markets are a zero-sum

> game. All of us can be winners, or all of us can be losers.

> I don’t concern myself with newbies coming up through the

> ranks becoming winners and then rob my pot. No chance!

Lots of good ideas here! Some are speculation (e.g. paragraphs 1 and 4), but they are interesting nonetheless.

In another post, 4xp goes on to write:

> People lose because they do not take time to learn. When

> I first started in 2004, I was working in a factory. I’d

> get home, then start learning about the markets. It took

> much experimentation and labor. I failed many times. Was

> it worth it! Well, let’s see. I wake up in the morning,

> go through my morning routine, which includes some quiet

> time and a trip to the coffee pot, then I make the long

> walk down the hallway to my home office, and report to

> work. Ahh, yes. It was worth it.

>

> Simply put, if you were training to be a doctor, you

> would have to go to school for 8 years, and pay all that

> money. Here, it depends on your learning curve and does

> not have to cost what a doctor pays. When you are

> finished and ready to enter the markets, you make more

> than the average doctor. But, yes, it take work and

> lots of time.

Five stars on the first paragraph!

With regard to the second paragraph, I disagree with making more than the average doctor. Not only does 4xp suggest it’s guaranteed, whether it’s even possible is highly dependent on starting capital level.

To be continued…

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | PermalinkWhat Percentage of New Traders Fail? (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on June 16, 2020 at 07:39 | Last modified: May 16, 2020 16:22Today I continue with excerpts from a Forex website forum discussion in 2013. The initial post, which tries to rebuke traditional wisdom, is Post #1 here. Forum content is unscientific and open to scrutiny. Do your own due diligence and buyer beware.

—————————

• Post #33, Nat:

> The brokerage data exaggerate the number of profitable traders.

>

> Say I start a new brokerage firm, and I sign up 100 new people

> every year and 95% fail and quit in the first year, the

> brokerage stats would be as follows:

>

> Year 1 – 100 new traders of which 5 are profitable (95% fail)

> = 5 profitable traders out of 100 or 5% profitable

>

> Year 2 – 100 new traders of which 5 are profitable (95% fail)

> plus 5 profitable traders from year 1 who are still on the

> firms books = 10 profitable out of 105 or 9.5% profitable

>

> Year 3 – 100 new traders of which 5 are profitable (95% fail)

> plus 5 profitable traders from year 1 and 5 from year 2

> = 15 profitable out of 110 or 13.6% profitable

>

> You also need to consider that profitable traders tend to have

> multiple accounts to offset the risk of losing all of their

> capital should their broker go bankrupt, or to take advantage

> of tighter spreads on different instruments. Losing traders

> tend to only have one account, therefore one profitable trader

> may be counted 3 or 4 times in these statistics depending on

> how many accounts they have.

• Post #39, King:

> I don’t believe the oft-quoted figure of 99%, 95% or 90% of

> new traders failing. You’re not designing a rocket that will

> travel to Mars.

This post makes me laugh now. First, as mentioned at the end of Part 3, I wonder if King has read the Brazilian day trading study? Second, as discussed in paragraphs 3 – 4 here, I think finding a viable trading system is extremely difficult. It may indeed be rocket science.

• Post #40, Nabi:

> The figures of profitable traders provided by the brokers do

> not account for the number of accounts being closed and opened.

>

> I read an article back in 2009 about IG index or IG markets…

> they had on average 50,000 accounts, year on year, which about

> 30% of them were profitable. The stand out figure I remember

> was that the number of new accounts opened per year 60,000.

> Whilst I cannot remember the exact figures I can clearly

> remember that the number of new accounts per year was

> greater than the average number of accounts held. If I recall

> correctly, the average account lifespan was about 3 months.

>

> …it still means the figures provided by brokers are worthless

> without the number of accounts open and closed within the year.

• Post #43, Trac:

> 51% profitable trades does not mean 51% traders are profitable.

>

> Also, check this DailyFX (FXCM) article… let’s use EUR/USD

> as an example. We know that EUR/USD trades were profitable 59%

> of the time, but trader losses on EUR/USD were an average of

> 127 pips while profits were only an average of 65 pips. While

> traders were correct more than half the time, they lost

> nearly twice as much on their losing trades as they won on

> winning trades losing money overall.

• Post #45, Kat:

> First of all, it says nothing about consistent profitability,

> because those 30% profitable in Q1 don’t have to be the same

> people in Q2, so 35% in Q2 can be made of different people

> than those 30% in Q1, etc.

>

> So you should accept that there is MAX 5% of consistently

> profitable traders making money every month (or quarter).

>

> And if you think that it is not true you probably still did

> not figure out how fking difficult this business is.

Here’s someone who clearly would believe the day trading study mentioned above.

To be continued…

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | Permalink[Non]Musings on Vendors

Posted by Mark on April 30, 2020 at 10:16 | Last modified: May 6, 2020 11:53I am not sure exactly what to make of trading system/software vendors, but I believe some understanding of them is essential to long-term trading success.*

Some great discussion about vendors is seen in online trading/investment forums. People debate different angles back and forth. I like to borrow commentary from forums and you have seen this several times. Earlier, I was reviewing a blog idea chock-full of forum excerpts that had 2,800 words. That’s almost an entire month of blogging for me! You probably don’t want to read that much and I don’t really want to type it. I tend to get negative and pessimistic when things start to reek of scam.

I do believe vendors have a place and I think everyone should come to some meaningful understanding on the topic. This isn’t about me getting on my “high horse” and “preaching the gospel.” If I don’t claim to have the answers and if I don’t try to indoctrinate you with them then it’s less work for me aside from being the wrong thing to do.

Today, therefore, I will not try to make a definitive case about vendors one way or another except to say you should know what they are. You should be aware that they exist. You should be able to identify them and I would encourage you to do some thinking on how they fit into the whole landscape of trading and the financial industry. For this reason, I am categorizing this post under “Financial Literacy.”

When I take an inventory of my overall thoughts and feelings, I come up with a few things:

- I know I am an oddity in terms of trading as a business—having replaced my full-time income and surviving eight years and counting: all things for which I am extremely grateful.

- I have a strong suspicion that something is wrong with the financial world.

- I have a strong suspicion many people working Finance do not have a good understanding about how money is made in the markets because they sell what they are told rather than trade.

- I know many trading clichés exist and most times, I can make just as good a case for the converse.

- I have found a great response to 95% of the tweets, posts, and other statements about the markets is “do you have any data to support that?”

- While so many people like to talk about winners, I prefer discussing losers. Talking to people besides myself is probably more enjoyable because they would rather involve celebratory concepts like “financial freedom,” “endless vacation,” “living in Maui,” and “eternal victory.” While these are great marketing anchors to bring people into the game, I am not sure they are reflective of reality.

- When I talk about my losers I sometimes get bitter and angry. While losers aren’t usually pleasant to see, I do believe them to be more important than winners with regard to trading as a whole.

- If I were to teach others then it would be more a scientific approach to the markets and an understanding of the fallacies and buried mines lying in wait than it would be lessons about successful set-ups and claims about how to generate profits. Avoiding losses and generating profits are synthetically equivalent.

The impetus for this post was EZ Color Trading featured on Season 8 of Dragons Den. In the end, only about half of is about vendors. I have therefore edited the title.*

Interestingly, when I browsed over to the EZ Color website, I got “404 Not Found.” This vendor apparently no longer exists.

* — This was originally written in November 2016, but the draft was never completed. Seeing

more recent blog posts (some linked) with overlapping content is very refreshing.