Option Fanatic, RIA (Appendix C)

Posted by Mark on February 10, 2020 at 13:41 | Last modified: May 6, 2020 07:10Today I will finish tying up the loose ends from this blog mini-series.

I left off discussing compliance for investment advisers (IA).

What limited information I have been able to obtain about standard guidelines implemented by compliance firms has left me somewhat dazed and confused. The red tape certainly does hinder/prevent action. I don’t think it’s all for naught though. With all the chicanery that has run rampant throughout the financial industry (see fourth paragraph here), prospective investors need to be protected.

Should I go forward with my own IA, I will probably hire a lawyer and/or compliance firm that specializes in these matters. I want to trade and study trading-related matters rather than getting stuck in all the red tape.

Should I go forward with my own IA, I may consider pursuit of a relevant credential. My doctorate is in pharmacy, which is not relevant. I don’t have a CFP, a CFA, or even an MBA. I don’t believe the credentials mean much with regard to character (honesty). Nevertheless, they are a symbol of expertise and they may be good for marketing. I would have to get licensed through the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), however, by passing the Series 7 and/or Series 65 exams.

Why would people want me to manage their money?

Don’t pick me because I’m good; I don’t believe picking the right stocks or making the right trades is even a thing. All I can do is put the odds in my favor, which is what what I do. From that point onward, if we lose then we lose and the possibility always exists that we will. This is a different mindset but it’s what I believe is really going on.

A better reason to pick me might have to do with my pharmacy experience. What about this:

> As a pharmacist, you trusted me with your life;

> you can certainly trust me with your money.

I truly believe this even though it may sound somewhat cheezy. I gave recommendations on medication, taught people how to use medication, and evaluated medication from time to time. If people could trust me with tasks like these—and they most certainly could—then they should also be willing to trust me with their investments.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkOption Fanatic, RIA (Appendix B)

Posted by Mark on February 7, 2020 at 11:01 | Last modified: May 5, 2020 14:14Today I will pick up with excerpt [1] from my last post.

The Investment Advisers Act of 1940 is a thing. Most people probably don’t know it, which would warrant a dedicated post.

The ’40 Act defines an investment adviser (IA) as any person or firm who is engaged in the business of providing advice to others or issuing reports or analyses regarding securities for compensation. The definition includes three parts with each as detailed as you might imagine any legal statute to be.

I disagree with the claim in [1] that “there is no need to be regulated.” If you are acting as an IA then you better be properly registered. Period. If you try to go “off the record” and get paid “under the table” then you’re engaged in tax evasion as well.

The same contributor wrote the following:

> One of the most important things to consider when you start

> managing other people’s money is how to deal with potential

> losses. Most guys who’ve been profitable jump into this business

> but when the first big loss arrives they have problems coping.

> What are you going to tell investors? How would they react to

> losses? Would they flee? How would this affect you financially?

> Everyone has different psychology. In my career as money

> manager, I’ve tried to select clients who are psychologically

> stable and predictable. I had once a client who liked to call

> he saw an article… about markets going down. He asked… am

> I sure every time nothing will happen to his money? In three

> months I decided to return his money and part ways for good.

Probably as much as anything else, this has been a good deterrent over the years against my entry to the IA business. For my own IA, I would be very cautious accepting money from strangers—especially people with little understanding about how the markets work. If working for someone else, though, I may not have much choice what clients I take.

I mentioned “red tape” in the fifth paragraph of Appendix A. Wikipedia describes red tape as follows:

> …an idiom that refers to excessive regulation… that is

> considered redundant or… hinders or prevents action or

> decision-making…

> …generally includes filling out paperwork, obtaining

> licenses, having multiple people or committees approve a

> decision… can also include “filing and certification

> requirements, reporting, investigation… and procedures.

I have studied most of the individual laws, but organizing everything into a manageable whole would be a herculean task. Compliance firms make it their business to handle these challenges for IAs. Compliance firms distill the various components of related laws (e.g. ’40 Act mentioned above, Uniform Securities Act, etc.) into generalized guidelines that will fit as many of their [prospective] clients as possible to maximize compliance firm efficiency.

I will continue tying up loose ends next time.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkOption Fanatic, RIA (Appendix A)

Posted by Mark on February 4, 2020 at 03:29 | Last modified: May 5, 2020 11:36In my quest to complete unfinished drafts, what follows are thoughts composed in July 2014 pursuant to this blog mini-series.

In these three posts, I talked about taking custody of client assets with regard to trade opacity and liability. Custody is where a brokerage or other financial institution holds securities on behalf of the client.

Another consideration with regard to custody is trading efficiency. Custody would easily allow me to place all trades at once.

I really have no need to take time shortcuts in executing trades because I would only be looking to trade as many separately managed accounts (SMA) as I could reasonably handle on any given day.

Perhaps more important than opacity or efficiency are the rolls of red tape I would need in order to maintain compliance with the “Custody Rule.” The Custody Rule, part of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, clarifies and builds upon the above [and Part 6] mention of “liability.” Its purpose is to provide protection for client funds or securities against the possibility of loss. I should do a complete blog post on the this since most people probably don’t know it exists.

For multiple reasons, my preference would be to avoid custody altogether. By maintaining control of their own accounts, clients will be able to see how much money they have and how the account is performing in real-time. I am not running a Ponzi scheme or Madoff fraud whereby I take client funds and provide only my trusted word about investment performance. Clients will still get monthly statements from their brokerage rather than only me [or my company].

Trading in SMA is probably in the best interests of the client and myself as adviser when starting out an RIA.

The next issue is whether to incorporate an investment advisory or to stay “off the record.” One internet source volunteered:

> There is quite a lot of incorrect advice on this thread… if you are

> carrying out investment business then that is a regulated activity

> and if you are not regulated then if it all goes wrong then you are…

> personally liable for all the losses. However it is not as clear cut as

> all that… although it is a grey area if you are only managing a few

> peoples money, (it comes under the broad umbrella of friends and

> family) and it isn’t some [elderly woman] whose life savings you are

> about to spunk up a wall, then there is no need to be regulated… I

> would also say this isn’t just my opinion, I have spent a fair few

> pennies getting legal advice on this very matter in the past. [1]

I will address this next time.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkEnvestnet Case Study (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on August 28, 2018 at 06:38 | Last modified: January 26, 2018 12:57As my second TPAM to investigate, I began discussion of Envestnet before really scrutinizing their offerings. I now suspect them to be just another garden-variety, plain-vanilla IA that probably generates subpar returns and significant improvement.

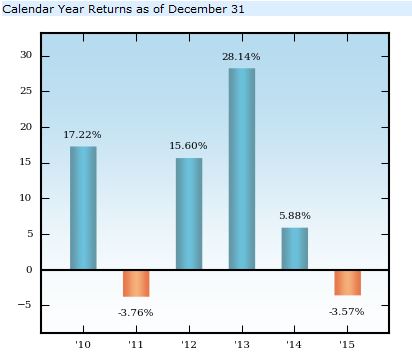

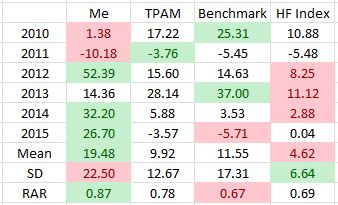

Even though the website content is “for investment professionals only” (a topic I thoroughly covered beginning here), after a bit of digging I was able to find a performance chart to assess my suspicion. Because the website appeared current when I looked at it in November 2017, I was somewhat perplexed as to why 2016 was not included. In any case:

For comparison:

Green (red) shading is the best (worst) for each row. Risk-adjusted return (RAR) is average annual return divided by standard deviation (SD). Benchmark is a broad-based equity index. Hedge fund (HF) index is provided by Barclay Hedge.

My RAR beat Benchmark by 0.20, which makes me think that I performed well. I did realize a higher volatility of returns but this can sometimes be worthwhile if justified by net return. Consider that a 25% smaller position size would have lowered SD below Benchmark while still realizing a 3% better annualized return. This is why I calculate RAR.

The TPAM fared better (RAR) than Benchmark but worse than me. Cutting my position size by 45% would have lowered SD below the TPAM while still realizing a better annualized return by 0.79%. I find that surprisingly close. To look at RAR and say “0.87 vs. 0.78 is a 10% performance improvement” is misleading.*

As another angle of comparison, remember XC’s claim of outperformance by 25-50 basis points. My response was that any self-directed trader should aim to outperform by more than that. 79 is not much better than 50. I would rather see at least 150 to justify a management fee at least 1% higher. Of course, as discussed here, even a tiny management fee of 0.11% could make sense for me given ample assets to manage and no additional overhead.

Contrary to my initial suspicion, I do not think Envestnet’s showing is subpar nor, therefore, garden-variety either. It would seem that I have to be impressed with them. As another way of describing RAR [normalized for SD],* they outperformed the index by 136 basis points. Now that’s what I’m talking about! Kudos to Envestnet.

So far in my exploration of TPAMs, I have seen one good, one bad, and two that provide significant improvement.

I will continue to do more performance research to determine whether my numbers are in the ballpark of what financial institutions might be looking for in a TPAM.

With regard to my own performance, the above table has more to offer. I will discuss that next time.

* I need to re-evaluate this performance metric, which has been a favorite of mine. It might come down

to a comparison of percent difference, which is a multiplicative measure, and the additive difference of

annual outperformance.

Why Can’t I Speak Directly to my Advisor about Investment Performance? (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on August 23, 2018 at 07:14 | Last modified: January 25, 2018 11:07Today I conclude discussion about why some investment advisers like First Ascent and Envestnet will not speak directly to the retail clients they ultimately serve.

Picking up where I left off, I responded to Sean Gillian of Longs Peak Advisory Services:

> Would CCO [Chief Compliance Officer] apprehension about

> performance reporting, which may lead to problems with the

> SEC if not done properly, be mitigated if IAs were willing to

> undertake the expense of becoming GIPS complaint and verified?

Gilligan responded:

> Some CCOs don’t want to be GIPS compliant… [and verified]…

> because they consider that a risk. False claims of compliance

> are a risk so they worry about taking on the additional

> burden of making sure they are complying with something they

> are not otherwise required to do. In reality the SEC likes

> GIPS, but they do take the claim very seriously to make sure

> you truly are compliant if you say you are.

I am reminded of a financial advisor perspective suggesting greater liability for publishing inferential statistics where I wrote:

> Advisers should not publish statistical analysis because they

> may overstate importance to the uneducated reader? In my

> opinion, statistical analysis is necessary to suggest a

> difference might be meaningful. And only the author can do

> the statistical analysis since the entire data set is rarely

> (if ever) presented in the article itself.

Backing claims with statistics is the right thing to do because empty claims are potentially contaminated with underlying motives of sales and marketing teams. Similarly, I believe [GIPS compliant and verified] performance reporting is the right thing to do for anyone investing money for others. In both cases, doing the right thing seems to be the risky alternative.

Are regulations to blame for this non sequitur? I asked Gilligan:

> Is it a matter of their compliance department (or firm) not

> having a full understanding of the regulations, which makes

> them recommend erring on the side of caution?

He said:

> It is… compliance wanting to keep their job simple.

I asked:

> Why are portfolio managers [PM] okay with this? Do they

> realize compliance directs them to operate in this way out

> of a desire to “keep their job simple?”

Gilligan responded:

> I wouldn’t say that PMs are okay with this. Many firms have

> an ongoing debate between PMs/Marketing and their compliance

> department regarding… [advertisement of performance]. Larger

> firms form working groups with representatives from both sides

> that work to determine a compromise that everyone can live

> with and that becomes their firm policy.

>

> I agree with you that GIPS compliance is best practice and

> there should be transparency, but unfortunately it gets more

> complicated when compliance people are overly scared of

> regulators finding deficiencies in what they do.

He also pointed out that GIPS compliance is separate from general regulatory compliance (e.g. SEC or state registration), which makes me wonder what compliance members get scared. I would not think a firm like Longs Peak gets scared of regulators finding deficiencies. Longs Peak has experience and specializes in GIPS compliance. If they have doubts about whether they can do their job properly then I certainly would not want to hire them!

Unanswered questions remain but compliance and regulations seem to be complicating matters about the right thing to do.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkWhy Can’t I Speak Directly to my Advisor about Investment Performance? (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on August 20, 2018 at 06:59 | Last modified: January 25, 2018 10:54First Ascent’s reason for not speaking to me directly made sense but I did not remember any such SEC requirement from my Series 65 study. Since I am trying to learn about the industry, I e-mailed Sean Gilligan of Longs Peak Advisory Services.

Gilligan wrote:

> The SEC does not require performance to be presented in a

> 1-on-1 setting, but they do deem anything… presented outside…

> a 1-on-1… to be an advertisement. Advertisements are subject to

> more rules and disclosures than what is required when meeting

> 1-on-1 for a customized presentation.

>

> Likely the performance they have available to show is model

> performance… [always highly scrutinized by the SEC] rather

> than a composite of all actual accounts, which is what GIPS

> would require… it is easier for them to have you sit down

> with an advisor… [who] can… explain… differences that…

> exist between… model and a live account than… to make a

> broadly distributed advertisement piece…

Sounds like a legal proceeding with attorney dictating what can or can’t be answered, how to phrase responses, etc.!

I replied:

> As an IA, I would want to publish performance without need for

> a 1-on-1 consult. Being GIPS compliant, would I be able to do

> this? What really frustrates me is the fact that if I were to

> hire an advisor who sold funds from this company, I could not

> directly speak with those executing discretion over my money.

I am not able to speak with traders at a mutual fund but I can call and speak directly with a fund representative!

Gilligan responded:

> To clarify, you can show performance outside a 1-on-1 as

> long as you have the right disclosures and have calculated

> performance in an acceptable manner (e.g. SEC requires

> broadly-distributed performance to be net-of-fees, while

> 1-on-1’s can be gross-of-fees). As a GIPS compliant firm you

> would be REQUIRED to distribute performance to all prospective

> clients… [this firm] you spoke with probably had an internal

> policy not to distribute performance. Many CCOs are very

> conservative… [on this] because they feel it is too high

> risk… [may lead to SEC issues if done improperly]. Most

> likely the firm’s CCO made a policy not to distribute and

> blamed it on the SEC when explaining… Truly they could if…

> they… [took] the time to include… necessary disclosures.

I don’t blame First Ascent for bending the truth. Simplified explanations are best for laypeople.

I will conclude next time.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkWhy Can’t I Speak Directly to my Advisor about Investment Performance? (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on August 17, 2018 at 07:29 | Last modified: January 24, 2018 06:35I want to be able to communicate with the entity responsible for investing my money. Like First Ascent, though, the Envestnet website says “for investment professionals only.” It is not intended for private investors. Private investors interested in their investment services are told to contact a financial professional.

I asked First Ascent about this and got the following response:

> We aren’t able to provide performance directly to clients

> without an advisor. Because we do not work directly with

> retail clients, and offer our strategies only through FAs, an

> advisor is required to… present gross-of-fee disclosures

> regarding advisory fees along with performance.

>

> If you are interested I’d be happy to have a call and answer

> any other questions that you have.

I prodded further and asked why they would not discuss performance with me directly.

> I apologize that we can’t provide performance directly. The

> reason is that the SEC requires performance be presented in

> a one-one-one conversation by an IA who can provide

> prospectuses of funds used and information regarding the

> structure and fees of the underlying ETFs and mutual funds.

>

> Our strategies may also vary in their underlying holdings

> based on the requirements or preferences of the advisors we

> work with, and some strategies are restricted to advisors from

> specific organizations, so performance may vary.

See my comments on separately managed accounts.

> Because of this we prefer to distribute performance directly

> through the advisors we work with who can provide these

> disclosures and make sure they are providing performance

> for the appropriate strategies that they use.

This actually seems like a decent argument to me.

> If you are interested in working with a financial advisor I

> am happy to provide the names of some firms that utilize

> our strategies in your area.

I give them kudos for being courteous.

All of this reminds me of behind-the-counter (BTC) products at the pharmacy. BTC has been controversial since 1984 when a proposal was filed to change ibuprofen from prescription to over-the-counter (OTC) status. Opponents argued the switch could cause patient harm. Instead of being granted OTC status, many suggested the drug be placed in a new class of medications to be sold only in pharmacies despite not requiring a prescription for purchase.

Proponents of BTC argued that pharmacist counseling would add a layer of safety.

BTC opponents included the pharmaceutical industry and clinical physicians. The former claimed pharmacist counseling would not benefit the consumer. The latter argued counseling and gatekeeping BTC drugs were tantamount to practicing clinical medicine, which pharmacists are not properly trained to do.

In the same way that I believe pharmacists can provide necessary education and enhance public safety by dispensing BTC products (e.g. insulin, Sudafed), I also believe it makes sense to have a financial [literate] professional [without underlying motives] present performance information to put it in the proper perspective.

I will continue next time.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkRoadblock ID

Posted by Mark on June 25, 2018 at 06:57 | Last modified: December 24, 2017 10:43Taking a few steps back can better help me to identify what still blocks my entry into the wealth management arena.

In November 2017, I called an adviser working for an LPL Financial affiliated firm. I had spoken with a recruiter two weeks earlier who did not provide much information. I wanted to find out more about logistics. Would I be able to work remotely? Would I have to find my own clients? Would I be able to trade options?

Ten minutes was all it took. He believed naked puts (NP) can pay off handsomely and get hurt severely based on his limited trading experience. As have so many others, he congratulated me on my decade of success in leaving pharmacy to trade options for a living. He said LPL is more conservative, though, and would probably not be the place for me. I asked where else I might look and he said this wasn’t his specialty and he really had no recommendations.

Another dead end.

If only as good PR and to engender trust, I think a number of advisory firms and broker-dealers that service non-accredited investors ban derivatives altogether. Derivatives do, after all, have a nasty reputation in the financial history of this country (another example here).

NPs involve great theoretical risk. Since 2001, NP performance has been far superior to that of long shares (i.e. max drawdown 3.7x smaller). Nevertheless, the leveraged approach could theoretically go bust sooner than long shares in the event of a market decline more severe than the 2008 financial crisis.

To be clear, the great theoretical risk with which I currently eat and sleep could be realized in the event of a surprise market crash of huge magnitude. Anything short of this should substantiate NPs as having less risk than long shares, but I would willingly discuss the worst case scenario with potential clients. This could make for a lousy sales pitch.

How do I resolve carrying such great theoretical risk and managing a strategy I believe to be better than stock?

The answer is high net worth (HNW) individuals (i.e. accredited investors). I alluded to this in a previous footnote. Recent experience has suggested my NP strategy be traded with an account no smaller than $250,000. I think strategies like this should be allocated up to 20% of an investor’s total net worth because of their potential to bust sooner than unleveraged alternatives. A HNW individual is likely to meet these criteria whereas non-accredited investors are not.*

I am hard-pressed to find work with an established wealth management firm, which might be my best opportunity to connect with HNW individuals. I have no relevant, credentialed financial education. I have no previous industry experience. I am intent on remaining focused on maximizing investment performance, which excludes me from providing other advisory services. I would insist on having the freedom to manage accounts my way [trading options]. I might insist on working remotely.

If I can’t work for an existing firm then I could take the leap and launch my own. I discussed this in detail here.

On a 2017 Shark Tank episode, Barbara Corcoran explained precisely what has kept me on the sidelines for over two years:

> It’s very hard to invest in a business where you don’t see

> a clear road to the finish line. Because I can’t see a way

> to get my money back, I’m out.

If I believe in myself enough then maybe the answer is to create a business plan, throw down the stacks to launch an IA, and to learn on the fly. I won’t find clients overnight but if I can secure one new $250,000 account per month then I could have $10M under management in four years (assuming 100% retention). That’s not half bad.

And maybe, with a partner who has industry experience with software/back-end technology along with sales and presentation know-how, I would progress even faster.

* The implication is that losing this 20% would still preserve 80% of the investor’s total net worth. In reality, some of the

other 80% would probably be invested in vehicles that would also lose significantly in the event of a market crash. While

I have computed Sharpe ratio, I have never computed correlation between my core strategy and its benchmark.