Custody Rule

Posted by Mark on March 31, 2020 at 07:04 | Last modified: May 15, 2020 10:58Today I go into more detail about the Custody Rule, which I first introduced here.

Custody fits into my world as described in this fourth paragraph. If I want to start managing wealth for others, then do I want to pursue work as an Investment Adviser [Representative] (IA) or hedge fund? Do I want to trade in SMAs (Appendix A, third paragraph)? Part of me doesn’t want the trouble of holding onto others’ money, and I would strongly suggest others not give their money over to anyone else.

From a legal perspective, custody is a complicated issue. Anyone [thinking about pursuing] working in the financial industry usually gets a question(s) about custody on the Series exams. If you are thinking about hiring a wealth manager or investing in a [hedge] fund, then custody should be understood to protect yourself.

Custody is a big deal because much fraud in the advisory business could be avoided if client assets were never turned over in the first place. This pertains to smaller operators. Don’t give your money to someone you met through a friend of a friend: you may never get it back. Full-service financial firms with a bank, IA, insurance company, recognizable brand name, etc., are okay. Custody is natural to have for an IA that is an affiliate of a large bank or broker-dealer, too.

I will now explain custody and detail some regulations surrounding it.

An IA has custody of client assets when the adviser actually holds funds/securities or can appropriate them. If the adviser can automatically deduct funds from the client’s account or write checks out of the account, then the advisor has custody of client assets. If the adviser has an ownership stake in the entity (e.g. broker-dealer) who maintains custody, then the adviser has custody of client assets. If the adviser is the general partner in a limited partnership or a managing member of an investment LLC, then the adviser has custody of client assets.*

Regulation of IAs is conducted through the state securities Administrator and/or the Securities and Exchange Commission.

By law (Uniform Securities Act), an IA must first discover whether the Administrator has any rule prohibiting custody of client assets. Custody should not be taken if such a rule exists.

When an IA takes custody, the Administrator must be notified in writing promptly. Promptly is not immediately nor is it months to years. Promptly is a reasonable amount of time and probably open to interpretation. I would not feel comfortable trying to unnecessarily try to drag this out.

Custodial IAs must maintain a higher minimum net worth, must provide an audited balance sheet to regulators and to clients, and must pay an independent CPA to conduct a surprise audit once per year. If the CPA cannot decipher securities and cash positions from the books and records, then the CPA is to notify the regulators promptly.

If an IA inadvertently receives client securities in the mail, then securities must be returned to sender within three business days to avoid IA being deemed as having custody. IA should also keep records explaining what happened to avoid having to maintain a higher net worth, having to get an expensive CPA audit, and having to update its registration information.

If an IA receives check from client payable to third party, then similar steps must be taken to avoid IA being deemed as having custody. First, third party must not be an affiliate of the IA. Second, check must be forwarded to third party within three business days. Finally, advisor must keep records as to what happened.

Custody is not just a minor inconvenience: it’s a bona fide PITA. Most IAs avoid it; banks and broker-dealers who provide custodial services often do so for a reasonable charge.

* — A fuller description would go into more detail about broker-dealers and corporate structure.

Envestnet Case Study (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on March 23, 2020 at 11:51 | Last modified: May 11, 2020 12:03Continuing on with my year-long organization project, this is an unfinished draft from August 2018 on performance.

I was confused about many things from this draft, which is now a completed post. I have figured it out; it was in reference to this Envestnet study. Part 1 was in May, Part 2 was three months later, and part three is seen below.

—————————

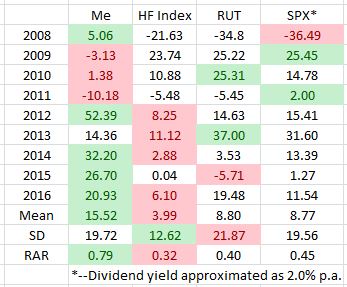

Kudos to Envestnet for outperforming the index (table from second link above). Furthermore, I only edged out Envestnet by 79 basis points when normalized for standard deviation (SD). As discussed in the first link above, however, because upside SD doesn’t hurt anyone I actually outperformed them by over 9% per year. This is a different perspective that leads to completely different conclusions.

My belief (based on a sample size of zero) has been that hedge fund (HF) managers and those who develop trading strategies for these funds are people like myself. I would think these are people who have studied and read everything they could find in the process of learning how to trade. I would think they are well-versed in system development and statistical fundamentals. I would also think they are well-schooled in quantitative analysis and the art of coding.

With that said, the HF performance is extremely interesting to me because hedge funds seem to significantly underperform:

The name suggests HFs aim to limit losses by hedging, which suggests a lower SD. They do, in fact, win the SD category. Because hedges generally cost money, I would not expect them to generate the highest absolute returns. Also in their defense, perhaps, is the fact that from 2008 – 2016 the market has been mostly up, which may not be where they excel since hedges are not needed.

I still find it hard to accept significant HF underperformance, though. From 2008 – 2016 HFs got trounced in mean return. Even on a risk-adjusted basis, the worst-performing index (RUT) beat them by over 20% and my 0.79 beat them by 146% over those nine years! For a 2/20 (or even 1/10) fee structure, I just don’t see how the value proposition exists.

Or maybe this is substantiation that I am just that good? Perhaps I am, indeed, professional trader (TPAM) material.

Categories: Uncategorized | Comments (0) | PermalinkMeeting with Rob Pasick (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on March 21, 2020 at 14:01 | Last modified: May 5, 2020 07:01Today I conclude my notes from a meeting with executive coach Rob Pasick just over one year ago.

As opposed to starting an investment advisory (IA), Dr. Pasick suggested branding myself as a domain expert and marketing that way. He said much of industry today is centered around knowledge. I mentioned this blog, which I use to keep myself on task. He asked how many followers I have and I said I don’t publicize it or track analytics since it doesn’t serve a marketing purpose (nothing to market). He talked about potentially self-publishing a book (he has two, which he gave me gratis).

He suggested I could also start a podcast, make professional use of financial media, and increase my exposure to the point that others would seek my services. Many people are simply too busy to manage their own money or just flat-out don’t want to deal with it and are willing to hand this off to “professionals.” He is aware of the migration to robo-advisors in modern-day asset management.

A related question he asked is whether I have any special sort of intellectual property (IP) to sell or whether my success is due to hard work. I said I feel strongly about options, which I discussed in this blog mini-series. However, I don’t want take up the cause of why options are better and the traditional approach to asset allocation is bad, which echoes more along the lines of IP (see second paragraph here). While I could be a small voice in a [relatively small] chorus, some individuals already dedicate themselves to pounding that table. Besides, while I do think traditional garden-variety asset management (sans options) is lackluster, I still believe they offer significant improvement (fifth paragraph here).

Finally, Rob extended an invite to his Leaders Connect monthly networking event. I really didn’t see how something like that would help me. In order to network and build my business, I need an asset management business (an IA) to build.

I asked him if he has worked with IAs before in context similar to my own. He said he has never worked with someone looking to build from the ground up. He has worked with existing IAs to build their businesses, though, and he has worked with financial advisors for national firms looking to become independent. He sounded confident in being willing to work with me…

…but as mentioned in the beginning, things like this have a price. His charge is about $300/hour. He suggested a three-month time frame to start at a cost of roughly $1,000 per month. He suggested it might take six months to really make an impact at a cost of roughly $5,000. In the beginning, he mentioned asking for a percentage of my new business as a fee. That would be more akin to a fee schedule I can see myself accepting.

If I knew up front this would grow into something successful, I’d bring multiple checkbooks. Since I don’t, as mentioned in the third-to-last paragraph here, the decision is very difficult for me to make.

Categories: About Me | Comments (0) | PermalinkMeeting with Rob Pasick (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on March 18, 2020 at 14:50 | Last modified: May 4, 2020 15:46Today I continue reviewing a meeting I had roughly one year ago with executive coach Rob Pasick.

As a second alternate to starting an investment advisory (IA), I could form the previously-mentioned “option trading workgroup” with the primary focus being practice of various option trading strategies (not the research discussed near the end of Part 1). Once familiar enough through practice or backtesting, perhaps, I should feel more comfortable adding different strategies to my regimen. These could serve as future profit centers.

Pasick tried to get at my true motivation for starting an IA by asking why I am not content sitting at home and continuing to trade for a living. I said it feels like a logical next step if I am able to trade successfully for myself. I also said it would also be a challenge—meaning that it would force me to practice weaknesses that I can hopefully turn into strengths.

Starting a business with actual clients would help reclaim my professional edge. This is a reference to getting “soft” rather than having soft skills. Working for someone else requires us to meet explicit goals and requirements. We typically have a dress code (other than sweats and underwear). We have places to be and deadlines to meet. We have presentations. We have protocol to organize and keep straight in case the supervisor makes a surprise visit. All of this represents solid discipline that, for the most part, I don’t need when working for myself (although I believe retaining these practices would increase probability of success even in the latter case). Here is an interesting post about working for oneself.

I explained that I could make some of these things happen just by spending a bunch of money. I could spend money to start an IA or hedge fund. I could hire someone to build me the automated backtester. As discussed in the fourth paragraph here, though, it’s really difficult for me to do these things when I don’t see a clear path to assets. I said the one thing I can’t guarantee by spending money is a successful new business venture.

This is where I need the plan and a vision. A business coach could probably help with this.

I’ll conclude next time.

Categories: About Me | Comments (0) | PermalinkMeeting with Rob Pasick (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on March 13, 2020 at 06:54 | Last modified: May 4, 2020 14:26Upon recommendation from a friend, I met with Dr. Robert Pasick one year ago. I composed this post (never finished) to serve as personal notes of that session.

Rob is an executive coach. I’m not sure if my referral had friendly contact or business in mind, but Rob is all business and he made that quite clear.

Not that I should really expect anything less—and I don’t. If ever the end product is making money, then it would seem a willingness to pay for the service is in order. I discussed this in the second paragraph here.

I started by reciting my 60-second elevator pitch:

> After working several years as a staff pharmacist and pharmacy manager, I retired

> to start a securities trading business at the age of 36. This has been a journey

> without clients or co-workers that has required extensive self-study, intrinsic

> motivation, and outside-the-box thinking. I have since learned a great deal about

> the mechanics of trading and investing. I have succeeded at replacing a six-figure

> pharmacist salary by posting average annual returns in excess of 15% from 2007

> onward. Having risked my own hard-earned capital to learn the craft, I now seek

> to manage wealth for others.

I explained some of my road blocks. The main one is lack of a sales background (see fourth paragraph here). Another is the fact that I trade options, which the financial industry views as extremely risky (as discussed here). He later noted the lack of a network of wealthy individuals who say “here’s a few million for you to manage… we love you, Mark!” is another block for me.

I have recently felt the need to really “network my *ss off” to get this business going. I also consider networking to be a weakness since I am not practiced at it.

Rob did not understand my sense of loneliness, which I proceeded to clarify. I said I have been unsuccessful at finding other full-time, independent, retail traders like myself (not of retirement age, but that’s not as important provided they have sufficient interest and dedication to collaborate) who trade for a living. In the absence of an investment advisory, which is probably #1 on my list of desired next steps, I could potentially form a research team to build the automated backtester (see paragraph #8 here) and proceed with my extensive list of research topics. That could shape my future trading* and/or serve as a foundation for professionally managed accounts.

I will continue next time.

* — I have since become more interested in trading futures, as discussed in many posts since (e.g. here).

Categories: About Me | Comments (0) | PermalinkIn Need of Performance Update

Posted by Mark on March 10, 2020 at 09:05 | Last modified: January 12, 2022 09:15One of my blog projects for the year is to get more organized by converting drafts to completed posts.

With a bit more work, incomplete drafts can become completed posts. Entering this year, I had over 30 entries in the “drafts” folder—some in excess of 450 words, which is my usual target. Completing these long drafts is a major coup because for less than the time it takes me to finish one from scratch, I can easily generate two, three, or even four complete posts.

With regard to these drafts, I typically write something like:

> In the longshot case that someone out there could possibly benefit

> from any of this, what follows is this post from August 2018.

Some of the drafts are well thought out, but I honestly have no idea where they fit. Some are without reference links to guide me. Some (like this one) are excessively complex and hard for me to decipher. I have no excuse for the latter except poor writing, quite honestly. Because they are just drafts I’m looking to complete, I include them and leave the decryption to you.

What follows is especially “in case someone out there could possibly benefit” content. Although it reminds me that a performance update is overdue, I am not sure what six-year period is being described. Perhaps when I go back and calculate performance, I will be able to resolve what follows. This post is therefore a call to action as stated in the title.

—————————

Keep in mind that my performance during said six year window, as discussed last time, was disappointing. However, showing performance since I started trading full-time provides evidence that I have done well overall. I believe the approach I have used recently is more disciplined, systematic, and therefore better than what I did in the early years of 2010 – 2014.

Then again, my stated 2010 – 2014 performance is not exactly bad. The high standard deviation (SD) hurts but that SD is to the upside. Upside SD will not cause sleepless nights, which is why a separate statistic differentiates upside from downside variance (Sortino Ratio). My 2012 return in excess of 50% is a major contributor to the high SD, which leaves risk-adjusted return much to be desired. Realistically speaking, though, clients would never complain about that.

Also with regard to multiplicative versus additive, what shocked me was to see a 10% improvement on the RAR ratio amounting to only 79 basis points. The problem with RAR is that it is unitless. 79 basis points is not 79 basis points, either. From 10% to 10.79% is only a 7.9% improvement whereas from 5% to 5.79% is a 15.8% improvement. When thinking in terms of management fee and overall compounded returns, we think about the additive difference.

Categories: Accountability | Comments (0) | PermalinkEnamored with Day Trading? (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on March 5, 2020 at 10:32 | Last modified: May 4, 2020 12:11Today I will finish up the last post by getting into some actual data about day traders.

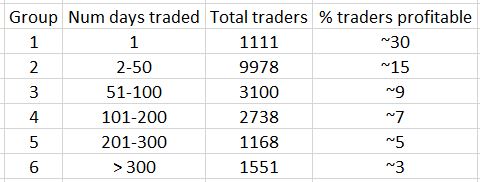

Chague et al. tracked 19,646 day traders from 2013 through 2015. This study received lots of buzz in Brazil. In addition to being extremely popular, day trading is also very controversial there.

The results boiled down as follows:

These data suggest day trading and casino roulette share similar odds of winning. The more people day trade, the better the chance they have to lose everything.

Chague et al. explain the results run contrary to self-selection. In self-selection, individuals with better performance generally persist in an activity. This is common in activities that exhibit “learning by doing.” Michael Mauboussin, in The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing (2012), agrees: practice does not make perfect when the outcome is due to luck rather than skill.

Trading educators want us to believe something altogether different. I often see [day] trading advertised as a craft to be developed over time. I won’t be overnight sensation. It takes hard work. The more I practice, the more classes I take, the more mentoring sessions, the more I spend on this education, the more I will succeed. In the current study, empirical data along with statistical regression analysis showed performance to be deficient with those trading longer faring even worse.

Despite the poor averages, perhaps those who end up in the green are a smashing success. Looking at the 47 out of 1,551 day traders who were profitable after 300 days:

- Only 17 earned more than the Brazilian minimum wage (16 USD/day)

- Only eight earned more than an newbie Brazilian bank teller (54 USD/day)

- One earned 310 USD/day

For all the stress and strain of day trading, the chance of making a respectable $78,000/year was 0.06% and the chance of making more than an entry-level bank teller wage ($13,608) was 0.5%. No windfall profits were to be found with tiny profits few and far between. The average daily result was a loss of $49.

Even to realize the entry-level bank teller wage, one had to endure a large variability of returns. For the eight mentioned above, the daily profit ranged from $632 to $3308. In other words, that $54 average profit/day was usually between -$578 to +$686 per day for the most consistent and -$3254 to +$3362/day for the most volatile. Sleepless nights, anyone?

If the outlook isn’t bleak enough already, Chague et al. explain why their study is likely to overestimate actual performance. First, income taxes and other relevant expenses (e.g. trading platform cost, courses) were not included. Second, only days where total contracts bought equaled total contracts sold were included. They cite a study by Juhani Linnainmaa (University of California at Berkeley, 2005) that says retail day traders are reluctant to close losers (called the “disposition effect”). Days with unequal numbers of contracts bought versus sold were likely losers, therefore. By not including these in this study the abysmal reported day trading performance is, itself, artificially inflated.

Chague et al. conclude “it is virtually impossible for an individual to day trade for a living, contrary to what the brokerage specialists and course providers often claim.”

This is certainly something to think about!

Categories: Uncategorized | Comments (0) | PermalinkEnamored with Day Trading? (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on March 2, 2020 at 10:34 | Last modified: May 4, 2020 11:19The next two posts are an absolute must-read if you have any interest in day trading for a living (second-to-last paragraph).

As I have discussed many times, data is the financial industry is frequently absent. This blog mini-series focused on the lack of performance reporting. This post focused on the lack of evidence to support technical analysis.

Now we have some actual data!

Today’s post is based on “Day Trading for a Living”: an August 2019 article by Fernando Chague, Rodrigo De-Losso, and Bruno Cara Giovannetti out of the University of São Paolo in Brazil. I encourage you to take a look at the full manuscript.

Chague et al. talk about the lack of quality data about the odds faced by people who choose to try their hand at full-time day trading. The few studies that exist do not focus on individuals who trade regularly, which “largely overstimates the odds” of having success. Second, the few studies that exist do not follow individuals from their first trade, which makes it difficult to understand whether learning is possible in this domain. Finally, the few studies that do exist sample periods that predate the modern-day trading landscape, which includes “fierce competition of algorithms and high-frequency traders.”

Futures trading in Brazil is very popular. Chague et al. cite a 2018 report from the Futures Industry Association stating annual volume of the mini-Ibovespa futures totaled 706 million contracts: much greater than the E-mini S&P 500 Futures (445 million contracts) and S&P 500 Index Options (371 million contracts). Futures and options trading volume of the Brazilian Exchange ranked third worldwide (2.57 billion contracts). The population of Brazil is approximately 40% that of the USA.

This is basically to say that day trading in Brazil is virtually a national pastime—much more popular than in the United States.

The Brazilian futures industry is similar to the USA. On one [large] side of the spectrum are the social media day trading “gurus,” vendors selling day trading systems, and lots of [supposedly?] profitable indicators/newsletters for sale. These are entities that have been presumably advertising and profiting throughout the industry for years. On the other [tiny] end of the spectrum are economists, social scientists, and data scientists.

Remember this excerpt?

> The oft-quoted statistic that 90% fail within five [1-2?]

> years supports this. I don’t know who [if?] did the original

> study but it is consistent with what I’ve seen of human

> nature from attending trading groups.

The time has finally arrived to see how this shakes out by putting some actual context behind it.

Categories: Uncategorized | Comments (0) | Permalink