My Journey (2019 Update)

Posted by Mark on September 24, 2019 at 09:52 | Last modified: March 27, 2020 11:07My focus has definitely shifted since I took a break from blogging.

2018 was first the losing year since I started trading full-time 11 years ago. That was certainly a wake-up call. I decided my trading approach was too risky to be doing with more than a limited portion of the account (akin to what I discussed in the second paragraph here). As a result, I have traded a small position size all year. While I have been profitable, I have significantly underperformed the benchmark.

My focus has gradually turned toward incorporating other asset classes in addition to equity options. I hope such diversification can increase total returns more than drawdown thereby improving my risk-adjusted return.

One way to accomplish this is to trade a basket of long uncorrelated futures. In other posts, I will detail my reasoning and plan for this strategy. Said discussion also begs for some space devoted to the concept and implications of correlation.

Another way to trade multiple asset classes is to develop multiple trading strategies. I will delve into this next time.

Categories: About Me | Comments (0) | PermalinkBeen a Long Time!

Posted by Mark on September 19, 2019 at 14:53 | Last modified: March 23, 2020 15:13Welcome back!

I’m actually saying that to myself because from your perspective, nothing may be different. Truth be told, however, I took a relatively long (for me, anyway) hiatus from blogging.

Worry not, though: this has happened before!

It happened here.

It happened here.

It happened here.

It’s now happened again.

But as I say with the omnipresent COVID-19, which now dominates the headlines and the structure of our everyday lives, we will get through this. I will ease back into my writing, which should help me go faster. I will relearn WordPress (and perhaps even update). I will relearn what HTML I need to manage the behind-the-scenes formatting of these posts.

And hopefully, I will bring you much more in the way of useful content. I certainly have been doing some interesting stuff, and I would love to be able to bring some of that to you.

Stay safe out there!

Categories: About Me | Comments (0) | PermalinkTesting the Noise (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on September 13, 2019 at 06:16 | Last modified: June 10, 2020 11:36I am now ready (see here and here) to present detailed results of the Noise Test validation analysis.

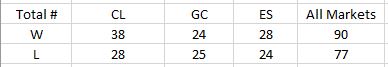

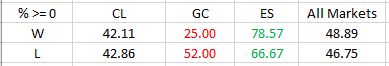

The strategy counts by market are as follows:

DV #1 (original equity curve positioning within the simulated distribution) breaks down as follows:

Frequencies are virtually identical for CL regardless of group (winning or losing strategies). Differences are seen for GC and ES with green and red indicating a difference as predicted or contrary to prediction, respectively. The more simulated curves that print above the original backtest, the more encouraged I should be that the strategy is not overfit to noise (see third graph here for illustration of the opposite extreme).

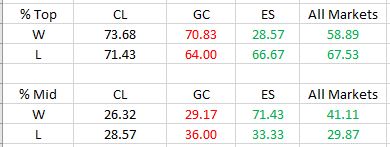

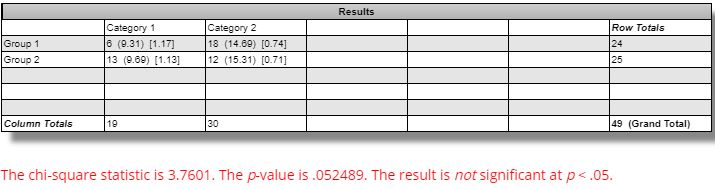

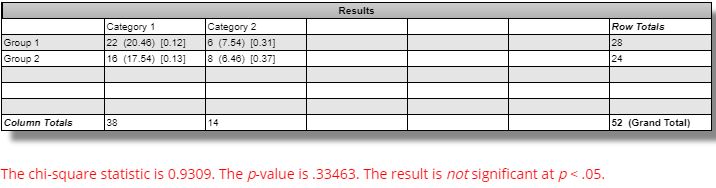

The difference in winning and losing strategies for ES is statistically significant per this website:

The difference between winning and losing strategies across all markets is not statistically significant:

DV #2 (percentages of strategies with all equity curves finishing breakeven or better) breaks down as follows:

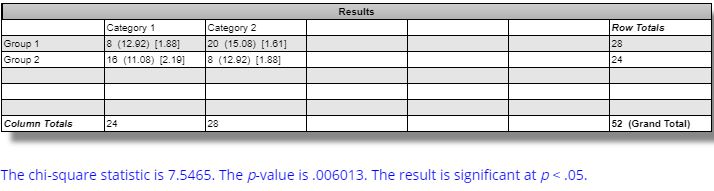

The difference seen between winning versus losing GC strategies is marginally significant (questionable relevance and even less so, in my opinion, due to smaller sample size):

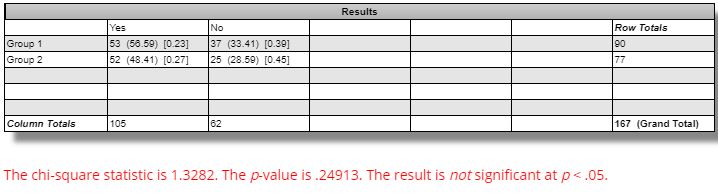

The difference seen between winning versus losing ES strategies is not statistically significant:

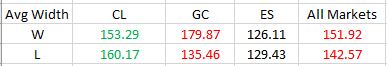

DV #3 (average Net Profit range as a percentage of original equity) breaks down as follows:

We should expect the simulated equity curves to be less susceptible to noise and therefore lower in range for the winning versus losing strategies. Across all markets, this difference is not statistically significant [(one-tailed) p ~ 0.15]. The difference for GC is statistically significant [t(49) = 2.92, (one-tailed) p ~ 0.003]: in the opposite direction from that expected.

Based on all these results, I do not believe the Noise Test is validated. The reason to stress potential strategies is because of a positive correlation with future profitability. I built 167 random strategies that backtested best of the best and worst of the worst. Unfortunately, I found little difference across my three validation metrics between extreme winners and extreme losers. My ideal hope would have been 12 significant differences in the expected directions. I may have settled for a few less. I got two with only one in the predicted direction.

Perhaps I could at least use Noise Test DV #1 on ES. I might feel comfortable with that if it were not for DV #3 on GC—equally significant, opposite direction—and an overall tally that suggests little more than randomness.

One limitation with this analysis is a potential confounding variable in the number of occurrences of open, high, low, and close (OHLC) in the [two] trading rules. My gut tells me that I should expect number of OHLC occurrences to be proportional to DV #3. A strategy without OHLC in the trading rules should present as a single line (DV #3 = 0%) on the Noise Test because nothing would change as OHLCs are varied. I am uncertain as to how X different OHLCs across the two rules should compare to just one OHLC appearing X times in terms of Noise Test dispersion.

I cannot eliminate this potential confound. However, this would not affect DV #1 and would perhaps only affect DV #2 to a small extent. More importantly, the strategies were built from random signals, which gives me little reason to suspect any significant difference between groups with regard to OHLC occurrences.

Categories: System Development | Comments (0) | PermalinkTesting the Noise (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on September 10, 2019 at 06:10 | Last modified: June 10, 2020 07:05Today I want to go through the Noise Test validation study, which I described in Part 2.

As I was reviewing screenshots for data evaluation, a few things came to light.

The consistency criterion (second-to-last paragraph of Part 2) is not an issue. All 167 strategies were “consistent” according to the Noise Test. When I decided to monitor this, I now wonder if I was remembering back to the Monte Carlo test instead.

Instead of consistency, I realized on some occasions all of the simulated curves were above zero. This percentage became dependent variable (DV) #2 and implies profitability regardless of noise. DV #1 describes where [Top, Mid(dle), or Bot(tom)] the original backtest terminal value falls within the equity curve distribution. DV #3 is net income range as a percentage of terminal net income for the original backtest.

I never saw the original backtest fall in the bottom third of the equity curve distributions (Bot, DV #1). This would be a most encouraging result that the software developers never presented as an example (see Part 1). Thanks for not deceiving us!

I found myself making some repetitive comments as I scored the data. On 19 occasions, I noted the original equity curve to be at the border of the upper and middle third of the distribution. Since equity values were estimated (platform does not have crosshairs or a data window), I simply alternated scoring Top and Mid whenever this occurred. I did not wish to feign more accuracy than the methods provide.

Also taking place on 19 occasions was a single simulated equity curve (out of 101) finishing below zero. One makes a big difference since the criterion is binary: all curves either avoid negative territory or they do not. This occurred 10 times for CL (split evenly between winning/losing groups), four times for GC (split evenly between winning/losing groups), and five times for ES (four winning and one losing strategy).

I recorded one CL strategy with an extremely profitable outlier and one GC and ES strategy, each, with an extremely unprofitable outlier.

I will present and discuss detailed results next time.

Categories: System Development | Comments (0) | PermalinkTesting the Noise (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on September 5, 2019 at 07:21 | Last modified: June 14, 2020 14:01Many unprofitable trading ideas sound great in theory. I want to feel confident the Noise Test isn’t one of them.

One big problem I see with the system development platform discussed last time is a lack of norms. In psychology:

> A test norm is a set of scalar data describing the performance

> of a large number of people on that test. Test norms can be

> represented by means and standard deviations.

The lack of a large sample size was part of my challenge discussed in Part 1. The software developers were kind enough to offer a few basic examples. The samples are singular and context is incomplete around each. I need to validate the Noise Test in order to know whether it should be part of my system development process. Without doing this, I run the risk of falling for something that sounds good in theory but completely fails to deliver.

I will begin by using the software to build trading strategies. I will study long/short equities, energies, and metals. I will look for the top and bottom 5-10 in out-of-sample (OOS) performance for each with OOS data selected as beginning and end (doubling sample size and re-randomizing trade signals to get different rules). I will then look at the Noise Test results over the IS period. If the Noise Test has merit, then results should be significantly better for the winners than for the losers.

I will score the Noise Test based on three criteria. First, I can approximate profitability range as a percentage of original net profit. This is understated because the Net Profit scale differs by graph based on maximum value (i.e. always pay attention to the max/min and y-axis tick values!). Second, I can determine whether the original equity curve falls in the middle, near the top, or near the bottom of the total [simulation] sample. For simplicity, I will just eye the range and divide it into thirds.

The final criterion will be consistency. In stress testing different strategies, I noticed these Top/Mid/Bot categories sometimes change from the left to the right edge of the performance graph. Is an example where the original backtest lags for much of the time interval and rallies into the finish really justified in being scored as “Top?” Had the strategy been assessed a few trades earlier, it would have scored as Mid thereby looking better in Noise Test terms (i.e. simulated outperformance relative to actual). Maybe I include only those strategies that score Yes for consistency.

I will continue next time.

Categories: System Development | Comments (0) | Permalink