Recent Discouragement

Posted by Mark on January 30, 2018 at 06:54 | Last modified: October 24, 2017 14:56Back in October 2015, I saw this posted in one of my forums:

> Looking at my past recent trades, I am thinking Mon and Fri

> are not good days for me to trade. I am also thinking Tues,

> Weds, and Thurs might not be so good either.

Cause / Effect Illusions

Posted by Mark on January 25, 2018 at 07:26 | Last modified: October 24, 2017 11:28In 2008, Jennifer Whitson at UT-Austin and Adam Galinsky at Northwestern University published an article in Science that is relevant to trading the markets.

One study involved two groups of subjects watching two sets of images on a computer screen.

The first set of images was a series of paired symbols. Subjects were told the computer used a rule to generate the pairs and were asked to identify the rule. Group #1 received no feedback throughout the series whereas group #2 was randomly told “right” or “wrong” regardless of how they answered. This experimental design attempted to make subjects in the second group feel less confident for what was to come next.

The second set of “images” was nothing more than white noise. Upon flashing, all subjects were asked whether they saw anything and if so then what? The vast majority of responses were negative from subjects in the first group while subjects in the second group were significantly more likely to say yes.

Having experienced failure during the first set of images, group #2 approached the second set lacking a sense of control over its surroundings and was significantly more likely to falsely identify patterns.

In discussing the study, Whitson said:

> All of these false/illusory patterns are connected. All of

> them are influenced by lacking control so when people lack

> control, they are more likely to see stock market trends that

> don’t exist… they’re more likely to see conspiracies in the

> world around them that don’t exist because it’s our instinctive

> sense to try and react to the situation in which we lack

> control by making sense of it and understanding it even if it’s

> a false sense of understanding… this effect could explain why

> religion is so successful among the poor or disenfranchised.

> Whenever people feel like their lives are out of control, G-d

> helps them make sense of things… there is a lot of randomness

> in our lives. There is a lot of chaos. There are many, many,

> many things we do not control. And so we have to pick out of

> that chaos things that are meaningful to us to make a sensible

> story out of our lives.

In conclusion, the brain seems more likely to identify patterns in what would otherwise be viewed as randomness when it feels out of control.

As traders never have control over what the market does, we should be careful about seeing definitive patterns that may not actually exist.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | PermalinkIncremental Value (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on January 22, 2018 at 07:18 | Last modified: November 15, 2017 07:35I’ve been discussing the incremental value I would provide to an investment adviser (IA) as a result of outperformance.

The numbers get more interesting if I am able to outperform by 3%. Last time I discussed the incremental value (in terms of the 0.8% management fee) were I to return 7% or 8% (11% or 12%) rather than 6% (10%). If I were able to return 9% or 13%, though, then my incremental value over 25 years would be $102K or $196K, respectively. While still apparently low, my average management fee has now increased to 0.11%.

At some level of outperformance, I feel the management fee should be increased. From the perspective of trading as a business, annual losses are anathema. In the event this accompanies improvement over the benchmark drawdown, I still feel payment should be postponed until a new highwater mark is established. The caveat, as mentioned in Part 1, is that only qualified investors* can be charged performance fees per SEC rules.

Whether clients pay performance fees is up to the IA but I feel it’s fair for me to be paid more as a trader. This goes back to my Part 2 mention of getting more than 50% of the incremental fees. Number and size (AUM) of client referrals may always be proportional to relative performance. Although hard to definitively measure, the value of this may be significant.

It has gone without saying that some benchmark for performance comparison would have to be agreed upon before any of this is finalized. I would also make a case for risk-adjusted returns. Clients who sleep easier at night will be happier than those who are more stressed and fearful. This can be measured by Sharpe [Sortino] Ratio or volatility of monthly returns. As discussed above, I strongly believe this has value albeit difficult to make tangible. One never knows when new referrals might be the direct result of a happier, stress-free clients. One also never knows when a more linear equity curve might directly result in the decision to remain invested during a market correction that would otherwise have sent them screaming for the exits to lock in large losses. These are two extremely valuable possibilities.

If I had 25 million-dollar clients then I would be earning $29K/$63K/$102K or $55K/$120K/$196K per year for relative outperformance beyond 6% or 10%, respectively. While I would not expect to manage $25M immediately upon hire, contemplating numbers like these makes a trading gig more enticing—especially if the IA can persuade me that more assets are available contingent upon solid performance.

What I’m talking about is doing exactly what I do now—executing a trading strategy in which I strongly believe—with 26 accounts rather than just my own and having a good chance of being paid [well] over $50K per year for my efforts.** I could probably get on board with something like this.

* Qualified investors have a net worth, excluding primary residence, of at least $1 million or an annual [spousal combined]

income of at least $200K [$300K].

** All calculations taken from “IA(R) fees and earnings (hypothetical) (10-12-17).”

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkIncremental Value (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on January 19, 2018 at 06:44 | Last modified: October 13, 2017 12:01Last time I presented some initial calculations to determine the incremental value I might provide to an investment adviser (IA) as a result of trading outperformance.

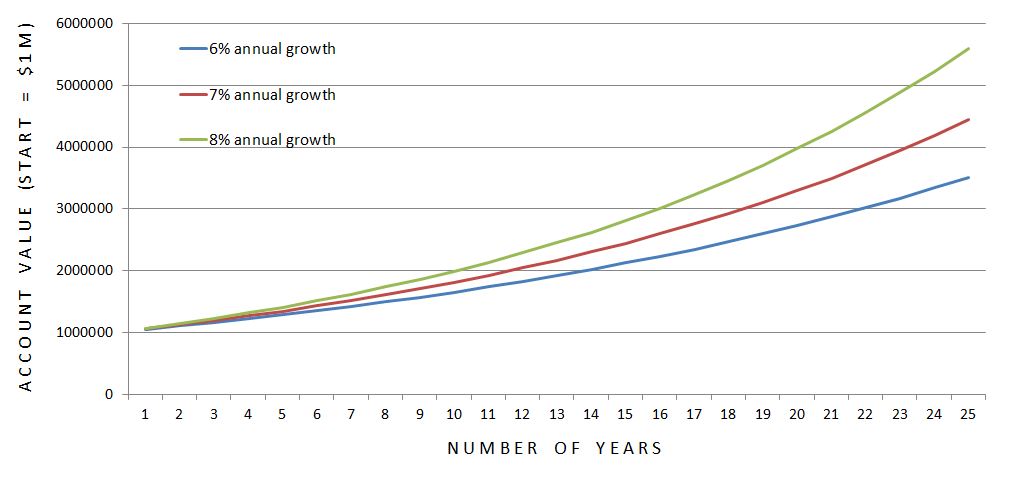

To isolate the impact of outperformance, I reran the analysis assuming 10% (rather than 6%) annual returns without me and 11% or 12% (rather than 7% or 8%) returns with me. Invested as previously described, $1M now becomes $8.86M, $11.11M, or $13.91M, respectively, over 25 years. The incremental value to the IA is now $110K or $240K for 11% or 12%. In splitting the difference I would earn $55K or $120K over that time.

Interestingly (to me), although outperformance is important, absolute performance plays a more significant role. Outperformance is identical on a gross basis in both simulations (1-2%). On a percentage basis, 7% or 8% vs. 6% is a 16% or 33% increase whereas 11% or 12% vs. 10% is a 10% or 20% increase. The significantly larger percentage increase is accompanied by a roughly equal ratio of incremental value share [($63K / $29K) = 2.18 ~ 2.17 = ($120K / $55K)] whereas the incremental value itself is almost double that for the 10%-12% versus the 6%-8% scenario.*

Note a similarity in calculated numbers for my share. I would earn $63K (over 25 years) by returning 8% instead of 6%; I would earn $55K by returning 11% instead of 10%. I would prefer a conservative estimate and project 2% outperformance over 11% returns. I can comfortably imagine annual returns of 11%, though. I will also do quite well when the overall market is moving moderately higher. While I will [profit but] underperform when the market is screaming higher, history has not presented many such episodes (e.g. second week of March 2009 onward and following the 2016 presidential election). I almost want to say that I can comfortably imagine 2% outperformance and 11% returns per year.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Time, as always, will tell.

I think outperformance would provide more value to an IA than higher absolute returns. It’s great if the IA makes 13% one year unless the benchmark returns 14%. One case where I think outperformance might not be good would be when the IA loses money for clients. Being down less than the benchmark is a marketable accomplishment, but clients may still be upset. Hopefully a conversation about the importance of minimizing drawdowns would correct their perception.

Next time I will talk more about my cut.

* If you are someone who spends modest time doing daily computation then you might be laughing at me just now for a failure to recognize basic arithmetic properties. Admittedly, I am a bit rusty with the mathematical proofs but believe you me, I still crunch numbers quite well!

Categories: Money Management | Comments (1) | PermalinkIncremental Value (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on January 16, 2018 at 07:54 | Last modified: October 13, 2017 11:42The time has arrived to break out the spreadsheets and start dissecting exactly how much I might earn as an investment adviser (IA) representative trading AUM.

I need to begin with some assumptions. Suppose the IA charges an annual management fee of 0.8%, which is assessed at the beginning of every year. As a conservative projection, let’s also assume the IA generates annual investment returns of 6%. A $1M account would therefore grow to $3.51M in 25 years.

Upon joining the IA, what if I were able to generate 7% or 8% per year?

Instead of $3.51M in 25 years, the account would now grow to $4.44M or $5.60M, respectively. That’s a significant boon for the client! This also brings incremental value to the IA in terms of management fees: an additional $58K or $126K, respectively, over 25 years. If I were to split that incremental value with the IA then I would make $29K or $63K with disproportionately more being earned as the years go by.

Keeping in mind that this trading gig must also be worthwhile to me, from a monetary standpoint I see some things not to like. First, my cut of the management fee ranges from 0.01% to 0.08% (or 0.14%). This seems minuscule. Second, that “incremental” detail is a killer. While I could make $29K or $63K over 25 years, if the client leaves the firm earlier then I will be effectively starting over with someone new. This feels like a mortgage where significant equity doesn’t start to build until later in the term. Although the incremental approach would keep me motivated to do well, I would rather be paid the average annual fee of 0.04% (or 0.07%). Besides, I don’t believe my history suggests a need for any additional motivation.

I could make a case for keeping all the incremental fees from my trading outperformance. The IA would benefit by earning more in fees as a result of my employment. My potential reward needs to be large enough for me to take on the challenge, though. If all the incremental fees went to me then it might represent a more acceptable wage (still small at an average of 0.08% or 0.14% over the 25 years) and a much happier client. That could lead to a larger book of business for the IA.

For now, in the spirit of keeping positive I think the bottom line is that I would make some money as a representative without having to do many of the back-office tasks required to launch my own IA. I wouldn’t have to file all the paperwork, come up with Form ADV, have legal work done, establish a new entity, hire a compliance team, deal with E/O insurance, cover all the overhead, or be forced to raise assets—the latter, especially, being no small feat.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkIncremental Value (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on January 11, 2018 at 06:38 | Last modified: October 13, 2017 11:50In contemplating transition from personal trading to wealth management as an investment advisor (IA) representative, I have struggled with fee structure. Thankfully the incremental value I bring to client accounts may buffer my cut as an intermediary.

What can I charge that is fair to the client and worthwhile to both myself and an IA that I represent?

In my opinion, “fair to the client” implies fees proportional to performance.* Consider this: if average annual hedge fund returns since 1970 are 12% while US equities have averaged 10% (approximations based on data from Bloomberg and Barclay Hedge) then does it make sense for the former to charge 2/20 (management/performance percentage fees) when the latter usually incurs a 1% management fee or less? I believe standard deviation is a second essential performance component and I would therefore be interested in comparing risk-adjusted returns. However, starting out with such a narrow edge in absolute return makes me skeptical that hedge funds will be able to justify a fee structure so extreme in comparison.

“Worthwhile to me” means my benefit must at least equal the cost. Working as an IA representative would require me to meet and speak with clients and with the IA, to be accountable to the IA, and perhaps to regularly commute to an office outside the home. These are big sacrifices to make especially when family is involved; much flexibility in my life would be lost. On the flip side, I would be associating [and hopefully collaborating] with co-workers and clients rather than operating in solitary confinement all day long. I would also be paid wages.

“Worthwhile to the IA” means the incremental value I provide is sufficient because a portion of IA revenue (management fee) would be redirected to me.

My initial thinking about the last two paragraphs was somewhat disappointing. I recently read about an IA charging 0.80% annually on the first $1M of assets under management. Thinking minimally, if I wanted to be paid anything more than 0.80% then the IA would be losing money to have me around!

Hope springs eternal when I consider the possibility of outperformance. Wouldn’t 11% annually be the same historical equity return mentioned above plus my 1% management fee or am I blinded by confirmation bias?

I will break out the spreadsheets next time.

* Per SEC rules, only qualified investors can be charged performance fees.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (1) | PermalinkTasty Statistics

Posted by Mark on January 8, 2018 at 07:33 | Last modified: October 11, 2017 08:48In December 2015, I posted on statistics and trading. In March 2017, I critiqued Tasty Trade’s (TT) “Market Measures” (MM) segment for omitting critical information. Today I present an August 2015 e-mail correspondence I had with the TT research team about a failure to include statistics when presenting backtesting results.

My initial e-mail was as follows:

> I’m a numbers guy, which is one reason I love the

> MM segment. One thing I would like to see are tests

> of statistical significance.

>

> For example, in a screenshot from 8/12/14, the

> takeaway is printed on the slide (16% and 3%). My

> training suggests if these numbers aren’t statistically

> significant then they aren’t very meaningful. I’d like

> to see how significant they are (e.g. p-value).

They responded the next day:

> I completely understand what you mean about adding

> statistical significance to studies… this is something

> we are trying to work into future studies. We have

> several members of our team who are very capable and

> have a strong history with… statistical analysis. I believe

> the major positive to including these numbers would be…

> more validity to our methodologies and studies… As for

> a potential negative, our main concern… would be

> barriers to entry. We want our MM and other segments

> to be accessible and, while complex, understandable to

> new and seasoned traders…

>

> Thank you so much for the feedback!

I responded a few days later:

> [With regard to the potential negative, you have] a

> very legitimate point. Statistics is difficult for many.

> I believe it provides essential information for those who

> understand, though. When a study compares two

> results, one is almost always going to be greater

> than the other… without the p-value, it’s impossible

> to know whether the difference is meaningful. Small

> mean differences and large standard deviations are not

> significant and only statistics can show us that.

>

> I totally get what you’re saying about being audience

> friendly… it doesn’t take much statistical discussion

> to get many people to gloss over and tune out.

>

> At the same time though, consider Tom Preston’s

> recent praise of work done by the research team:

>

> When they put results out there, we can

> stand by them both from a data accuracy

> and conceptual point of view.

>

> Can you without providing the statistics? Omitting

> statistics misrepresents the reality, in some cases,

> by suggesting meaningful differences exist when in

> fact they may not.

>

> Scientific analysis can always be scrutinized. I

> believe statistics should at least be presented.

> Omitting them may substantially undermine the Tasty

> Trade mission (to combat misinformation and lack of

> information provided by the financial industry), which

> Tom Sosnoff literally pounds the table to support.

Their final response:

> Thanks again for the feedback.

>

> Once again, I 100% agree with you that adding hard-

> hitting statistical numbers will add to studies for those

> who understand them. We are trying to implement this

> going forward… I have passed your ideas onto the team

> and emphasized that there are viewers… that want to

> see this kind of analysis.

I felt that was a promising e-mail exchange.

Nearly 30 months have now passed and I have yet to see a p-value reported on MM, though. I have seen every single episode.

I had one other controversial idea not shared in the e-mail:

> Maybe people who don’t or can’t understand statistics

> should not be trading. Or perhaps part-time trading in

> in small/hobby size is okay as opposed to trading full-

> time as a business.

I did mention critical thinking and statistical background in my post on prerequisites for trading as a business.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | PermalinkHindsight Bias

Posted by Mark on January 5, 2018 at 06:21 | Last modified: October 10, 2017 10:20By the way, Happy New Year, everyone! Today I will discuss a cognitive fallacy capable of ensnaring us all: hindsight bias.

Here is a forum post from July 2015:

> Why would anyone have their portfolio weighted with long puts in

> a major downtrend preceding 9/11? It makes no sense. Karen said,

> “stick with the trend.” A proper portfolio preceding 9/11 would

> have been selling calls on each rally and EXTREMELY LIGHT on the

> put side, if at all. Just look at the monthly chart; look at the

> size of the candles each selling month. Anyone selling naked puts

> in this scenario needs to look at the bigger picture first and

> understand the context of the current market they are in.

I responded as follows:

> I mean no personal insult but I think this is a very ignorant post.

>

> I claim ignorance because hindsight makes it easy to determine

> trend. How likely is your approach likely to work in the future?

>

> I don’t know what rules you suggest for use on a monthly chart

> but simply using a monthly chart means the number of occurrences

> is limited from the outset. If you don’t have a sufficiently

> large sample size then your approach may fall prey to curve-

> fitting: works in the past but not in the future.

>

> Discretionary guidelines can always be bent to fit pre-existing

> biases. What you have described (e.g. “monthly charts,” “size of

> candles”) is very nonspecific.

>

> Being specific means objective definition of rules. Only then

> can you backtest and begin validation. Author Kevin Davey

> suggests a good system may be found for every 100-200 tested.

> Do not believe it so easy to come up with a set of technical

> criteria capable of predicting the next big fall.

>

> You may say, “I can be wrong an extra time or two as long as

> I’m out before the fall.” I think this is a good point but

> realize that whipsaw losses can be significant and this may

> render adherence to your system very difficult. When it

> comes to losses, traders can be a fickle lot.

Hindsight bias [which also reminds me of future leak] is a common logical fallacy that must be recognized in trading and investing discussion/literature. The fallacy underlies artificially inflated performance claims. To stay on the path of consistent profitability, our challenge is to debunk such fiction and to minimize its consumption of our precious time and resources.

60 Seconds or Less

Posted by Mark on January 2, 2018 at 06:42 | Last modified: October 12, 2017 21:20I have found composition of an elevator pitch to be one of the more difficult things ever!

On multiple levels, describing what I do is tremendously difficult. I recently met with a résumé writing specialist. She said she had written 3,000 résumés in over three decades of business. After talking with me for 90 minutes she said “you still haven’t told me what it is that you do, exactly.”

But when it gets right down to it, I use my money to make money and I have done this successfully for the last 10 years!

THERE. I said it.

And I hate saying it because to some degree I feel it sounds arrogant. To me it carries undertones like “you have to endure a tough commute, work long hours and deal with the day-to-day stresses of a corporate job while I just sit at home in my sweats working a few minutes per day to pay the bills.”

Except that it is not arrogant since I have put in a great deal of hard work to create the business I now operate on a daily basis. A lot of outside-the-box thinking has also been implemented, which may be why it’s called “alternative investing.” For all this, for believing in myself, and for the risk I have taken in leaving an esteemed job as a pharmacist, I am to be commended.

And I am not threatening karma because every business day I take some time to remind myself of where I am, of the gratitude I possess, and of the challenges that lie ahead.

I strongly believe my experience qualifies me to manage client accounts; can I put together a brief 60-second pitch to present this opportunity?

Here’s my first attempt:

> After several years working as a retail staff pharmacist and pharmacy manager, I

> retired at the age of 36 to start my own securities trading business. This has been

> a journey without clients or co-workers that has required extensive self-study,

> strategy development, and outside-the-box thinking. Over the last 10 years I have

> learned a great deal about the mechanics of trading and investing. I have

> succeeded at replacing a six-figure pharmacist salary by posting average annual

> returns in excess of 15% since 2008. Having risked my own hard-earned money

> to learn, I now seek a broader application: wealth management for others.