The Pseudoscience of Trading System Development (Part 5)

Posted by Mark on June 28, 2016 at 07:48 | Last modified: May 10, 2016 12:29My last critique for Perry Kaufman’s system is its excessive complexity.

I believe the parameter space must be explored for each and every system parameter. For this reason, I disagree with Kaufman’s claim of a robust trading system. He applied one parameter set to multiple markets but I don’t believe successful backtesting on multiple markets is any substitute for studying the parameter space to make sure it’s not fluke. Besides, I don’t care if it works on multiple markets as long as it works on the market I want to trade.

When exploring each parameter space, the analysis can quickly get very complicated. I discussed this in a 2012 blog post. In Evaluation and Optimization of Trading Strategies (2008), Robert Pardo wrote:

> Once optimization space exceeds two dimensions

> (indicators), the examination of results ranges

> from difficult to impossible.

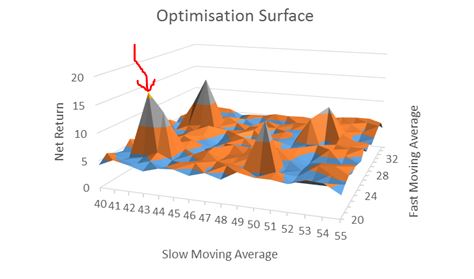

To understand this, refer back to the graphic I pasted in Part 2. That is a three-dimensional graph with the subjective function occupying one dimension.

For a three-parameter system, I can barely begin to imagine a four-dimensional graph. The best I can do is to imagine a three dimensional graph moving through time. I’m not sure how I would evaluate that for “spike” or “plateau” regions, though: terms that refer to two dimensional drawings.

For a better visualization of what I’m trying to say here, this video shines light on Pardo’s words “difficult to impossible” (and if you can help me spatially understand the video then please e-mail).

Oh by the way, Kaufman’s system has seven parameters, which would require an eight-dimensional graph.

At the risk of repetition, I will say once again that Kaufman is not wrong. Just because it doesn’t work for me does not mean it is wrong for him.

And that is why I have pseudoscience in the title of this blog series. That is also why I use the term subjective instead of objective function. A true science would be right for everyone. Clearly this is not. It’s wrong for me and it should be wrong for you but it is never wrong for the individual or group who does the hard work to come up with and develop it.

Categories: System Development | Comments (1) | PermalinkThe Pseudoscience of Trading System Development (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on June 23, 2016 at 06:51 | Last modified: May 8, 2016 10:42Today I want to continue through my e-mail correspondence with Perry Kaufman about his April article in Modern Trader.

Kaufman e-mailed:

> are not particularly sensitive to changes

> between 90 and 100 threshold levels, so I

> pick 95… Had it done well at 95 and badly

> at 90, I would have junked the program.

Junking the system and not writing an article on it would be the responsible thing to do. He can claim to be that person of upright morals but it doesn’t mean I should trade his system without doing the complete validation myself. I’m quite sure that even he would agree with this.

In response to my comments, Kaufman sent a final e-mail:

> I appreciate your tenacity in pursuing this…

> I’m simply providing what I think is the basic

> structure for something valuable. I had no

> intention of proving its validity scientifically…

> I’m interested in the ideas and I will then

> always validate them before using them. For

> me, the ideas are worth everything.

Kaufman essentially absolves himself of any responsibility here. He did nothing wrong in the article but I, as a reader, would be wrong to interpret it as anything more than a collection of ideas. It may look like a robust trading system but I have much work to do if I am to validate it and adopt it as my own.

What can give me the confidence required to stick with a trading system is the hard work summarized by the article but not the article itself. If the sweat labor is not mine then I am more likely to close up shop and lock in maximum losses when the market turns against me because paranoia, doubt, and worry will come home to roost. When I do the hard work myself (or with a team of others to proof my work) then I have a deeper understanding of context and limitations, which is what gives me the confidence necessary to stick with system guidelines.

If this sounds anything like discretionary trading then it should because I have written about both in the same context. It’s also the same reason why I recommend complete avoidance of black box trading systems.

Categories: System Development | Comments (0) | PermalinkThe Pseudoscience of Trading System Development (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on June 20, 2016 at 06:36 | Last modified: February 9, 2017 09:57I left off explaining how Perry Kaufman did not select the parameter set at random for his April article in Modern Trader. This may be okay for him but it should never be okay for anyone else.

The primary objective of trading system development is to give each of us the confidence required to stick with the system we are trading. I could never trade Kaufman’s system because I find the article to be incomplete.

In an e-mail exchange, Kaufman wrote:

> Much of this still comes down to experience and

> in some ways that experience lets me pull values

> for various parameters that work. Even I can say

> that’s a form of overfitting.

Kaufman’s personal experience is acceptable license for him to take shortcuts. He admits this may be overfitting [to others] but he doesn’t want to “reinvent the wheel.”

> But the dynamics of how some parameters work

> with others, and with results, is well-known.

Appealing to my own common sense and what is conventional wisdom, Kaufman is now saying that I don’t need to reinvent the wheel either. I disagree because I don’t have nearly enough system development experience to take any shortcuts.

> My goal is to have enough trades to be

> statistically significant (if possible),

> so I’m going to discard the thresholds

> that are far away.

I love Kaufman’s reference to inferential statistics. I think the trading enterprise needs more of this.

> Also, my experience is that momentum indicators…

Another appeal to his personal experience reminds me that while this may be good enough for him as one trading his own system, it should never be good enough for others. I feel strongly that when it comes to finance, the moment I decide to take someone’s word for it is the moment they will have a bridge to sell me that doesn’t belong to them in the first place.

Money invokes fear and greed: two of the strongest emotions/sins in all of human nature. They are strong motivators that provide strong temptation. I did a whole mini-series on fraud and while I’m not accusing Kaufman of any wrongdoing whatsoever, each of us has a responsibility to watch our own backs.

I will continue next time.

Categories: System Development | Comments (1) | PermalinkRandomization: Not the Silver Bullet

Posted by Mark on June 17, 2016 at 06:36 | Last modified: May 29, 2021 08:53Random samples are often a research requirement but I believe trading system development requires something more.

Deborah J. Rumsey, author of Statistics for Dummies (2011), writes:

> How do you select a statistical sample in a way

> that avoids bias? The key word is random. A

> random sample is a sample selected by equal

> opportunity; that is, every possible sample of

> the same size as yours had an equal chance to

> be selected from the population. What random

> really means is that no subset of the

> population is favored in or excluded from the

> selection process.

>

> Non-random (in other words bad) samples are

> samples that were selected in such a way that

> some type of favoritism and/or automatic

> exclusion of a part of the population was

> involved, whether intentional or not.

Randomized controlled trials have been said to be the “gold standard” in biomedical research but I do not believe randomization is good enough for trading system development. Yes it would be good to avoid selection bias but this is not sufficient. I wrote about this here. The only way I can know my results are not fluke is to optimize and test the surrounding parameter space. Evaluating the surface will reveal whether a random parameter set corresponds to a spike peak or the middle of a plateau.

This perspective on randomization concurs with my last post. Perry Kaufman selected one and only one parameter set to test and for that reason I took him to task.

As Rumsey’s quote suggests, statistical bias is never a good thing. E-mail correspondence suggests Kaufman did not pick any of the values in his particular parameter set at random. He selected them based on his experience and knowledge of market tendencies. My gut response to this is “just do the work and test them all.”

While this may or may not be feasible depending on how multivariate the system, it brings to light the main objective of trading system development. I will discuss this next time.

Categories: System Development | Comments (0) | PermalinkThe Pseudoscience of Trading System Development (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on June 14, 2016 at 06:15 | Last modified: May 4, 2016 10:01Last time I outlined a trading system covered by Perry Kaufman and offered some cursory critique. Today I want to cut deeper and attack the heart of his April Modern Trader article.

With this trading system, Kaufman presents a complex, multivariate set of conditions. He includes an A-period simple moving average, a B-period stochastic indicator, a C (D) stochastic entry (exit) threshold, an E (F) threshold for annualized volatility entry (exit), and a G-period annualized volatility. Kaufman has simplified the presentation by assigning values to each of these parameters and providing results for a single parameter set:

A = 100

B = 14

C = 15

D = 60

E varies by market

F = 5%

G = 20

I believe development of a trading system is an optimization exercise. Optimizing enables me to decrease the likelihood that any acceptable results are fluke by identifying plateau regions greater than a threshold level for my dependent variable (or “subjective function“). Optimization involves searching the parameter space, which by definition cannot mean selecting just one value and testing it. This is what Kaufman has done and herein lies my principal critique.

Kaufman should have defined ranges of parameter values and tested combinations. Maybe he defines A from 50-150 by increments of five (i.e. 50, 55…145, 150), B from 8-20 by increments of two (i.e. 8, 10… 18, 20), etc. The number of total tests to run is the product of the number of possible values for each parameter. If A and B were the only parameters of the trading system then he would have 21 * 7 = 147 runs in this example. The results could be plotted.

Here is what I don’t want to see:

[I found this on the internet so please assume the floor to be some inadequate performance number (e.g. negative)]

A robust trading system would not perform well at particular parameter values but perform poorly with those values slightly changed. This describes a spike area as shown by the red arrow: a chance, or fluke occurrence.

Kaufman claims to have “broad profits” with his system but I cannot possibly know whether his parameter set corresponds to a spike or plateau region because he did not test any others. No matter how impressive it seems, I would never gamble on a spike region with real money. Graphically, I want to see a flat, extensive region that exceeds my performance requirements. To give myself the largest margin of safety I would then select parameter values in the middle of that plateau even if the values I choose do not correspond to the absolute best performance.

Categories: System Development | Comments (1) | PermalinkThe Pseudoscience of Trading System Development (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on June 9, 2016 at 07:11 | Last modified: May 4, 2016 08:14I subscribe to a couple financial magazines that provide good inspiration for blog posts. Today I discuss Perry Kaufman’s article “Rules for Bottom Fishers” in the April issue of Modern Trader.

In this article, Kaufman presents a relatively well-defined trading strategy. Go long when:

1. Closing price < 100-period simple moving average

2. Annualized volatility (over last 20 days) > X% (varies by market)

3. 14-period stochastic < 15

Sell to close when:

1. Annualized volatility < 5%

2. Stochastic (14) > 60

Kaufman provides performance data for 10 different markets. All 10 were profitable on a $100,000 investment from 1998 (or inception). Based on this, he claims “broad profits.” Kaufman concludes with one paragraph about the pros/cons to optimizing, which he did not do. He claims this strategy to be robust as one universal set of parameters.

In the interest of full disclosure, let me recap my history with Perry Kaufman. I have a lot of respect for Kaufman because he has been around the financial world for decades. One of the first books I read when getting serious about trading was his New Trading Systems and Methods (2005). As a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed newbie, I even e-mailed him a few questions in thinking this was truly the path to riches.

Being a bit more educated now, I see things differently.

For starters, here is some critique about what jumps off the page at me after a second read. First, four of the 10 markets are stock indices (QQQ, SPY, IWM, DIA) that I would expect extremely to be highly correlated. “Broad profits” is therefore more narrow. Second, although the trading statistics all appear decent, the sample sizes are very low. Three ETFs have fewer than 10 trades and only two have more than 50 (max 64). Finally, Kaufman provides no drawdown data. Max drawdown may define position sizing and provides good context for risk. I feel this is very important information to provide.

When I first read the article, my critique focused on a different set of ideas. I will discuss that next time.

Categories: System Development | Comments (0) | PermalinkForecasting and Accountability

Posted by Mark on June 6, 2016 at 07:15 | Last modified: April 26, 2016 09:45From an article in the April 2016 Modern Trader magazine on oil price forecasting, Garrett Baldwin wrote:

> At the heart of it is the incapability of the human mind to wrap itself

> around the sheer size and factors that go into this global market. When

> something is this large with this many moving parts, we try valiantly to

> find shortcuts or justify one specific variable. Each day, a headline

> says that oil prices fell because of whatever factor an energy journalist

> can point to that day.

>

> It’s over-simplification at best, and malpractice at worst… And it’s

> clear that no one has a clue what oil prices will hit by the end of the

> year because of so many factors beyond our grasp. No one is suggesting

> that forecasting should be abolished, but history has shown that when

> it comes to accurately predicting oil prices, all bets are off. Are we

> willing to admit we’re just not good at this?

> …

> Right now, oil prices are hovering below $30 per barrel, a level that

> was deemed impossible just a few years ago. I remember sitting in a

> lecture with a prominent economics professor not long ago. He told

> the room that we wouldn’t see oil under $100 per barrel in our

> lifetime again. He somehow still has tenure.

>

> In the end, I still argue the real problem is that there is no

> accountability. People are allowed to make any prediction they want,

> and it is quickly lost in the 24-hour news cycle. When the prediction

> doesn’t come true, the blame falls on some unforeseen variable.

The article was on oil prices but it certainly is good information to know about financial forecasting in general. Baldwin’s words are consistent with those of Bob Veras in Doomsday Forecasting (a Primer): “nobody, including those who reported your alarmist views, will check up on your track record.” The lack of accountability allows anyone to forecast anything.

Personally, I believe the fault should not fall on the forecasters but rather on the readers who try to make use of the information. Forecasting is not actionable, period. That is why I categorized this post under “financial literacy.” Once I can identify content as a forecast, I can dismiss it and move on.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (1) | PermalinkLessons from David Dreman (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on June 3, 2016 at 06:42 | Last modified: April 21, 2016 07:56I want to wrap up this mini-series today on David Dreman by discussing a few more cognitive biases, or heuristics, and offering some commentary on effectiveness.

David Dreman may be a living example of a repetitive theme throughout this blog: ideas that sound good but truly have no merit. I make no performance claims about Dreman Value Management. I mentioned backtesting his idea of investing in out-of-favor issues because I have not done so myself. Contrarian investing is conventional wisdom discussed in books and seminars for traders, which is a big reason it resonates with me and feels right.

I will close with discussion of a few other types of cognitive heuristics.

Historical consistency leads to greater confidence about predictability. Dreman found investors have more confidence in a stock that consistently rises with 10% earnings growth than a more volatile stock with 15% earnings growth. Is a less volatile stock more likely to outperform into the future? That is an empirical question.

The anchoring heuristic describes a common human tendency to rely heavily on the first piece of information when making decisions. Other judgments are made in reference to the anchor, and bias exists toward interpreting other information around the anchor. For example, a stock purchase price defines what is “good” (higher subsequent prices) and “bad” (lower prices). These are purely subjective judgments. Mr. Market certainly does not care about my cost basis.

Finally, confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, remember, interpret, and favor information in a way to confirm preexisting beliefs or hypotheses while giving less consideration to alternative possibilities. The effect is stronger for deeply entrenched beliefs and emotionally charged issues, which would certainly include the prospect of making money!

Confirmation bias is the main reason I seek collaboration for trading system development, which I have written for a long time. I do not want to be blinded by confirmation bias if I get a whiff of something good. In this case, other critical minds can better maintain objectivity; the idea remains less emotionally-charged because it is not theirs.

Certainly I would rather be proven wrong in the development stage rather than with real money on the line. Confirmation bias circumvents this and collaboration is the antidote.

Categories: Wisdom | Comments (0) | Permalink