Covered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 33)

Posted by Mark on February 27, 2014 at 06:22 | Last modified: February 14, 2014 07:04Dollar cost averaging (DCA) is a CC/CSP position management technique I have alluded to in recent posts.

In Systematic Covered Writing, Rich MacDuff writes:

> The [DCA] strategy can be very advantageous

> when used with stocks that lose value… with a

> lower averaged cost basis, it will be easier to

> have the position go back to cash at a profit…

> [because] reaching a Continued trade status

> will occur at a lower strike price…

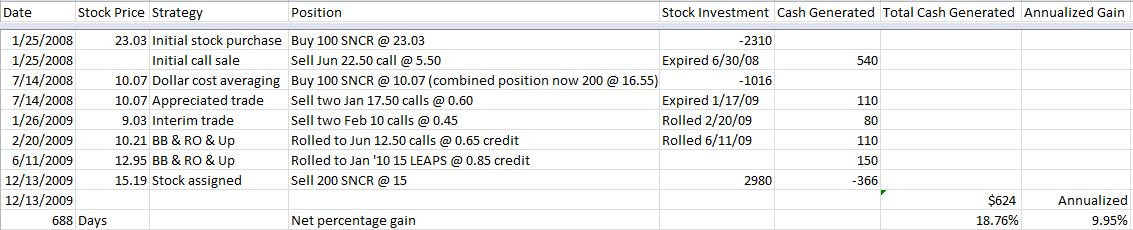

Here is a simplified example from the MacDuff archives:

In the first six months, SNCR fell ~56%. When a stock falls substantially, the short call strike will have to be lowered as little premium is available to sell regardless of expiration.

DCA lowers the cost basis (CB) over 28%, which leaves $6.48 less to recoup for position profitability. This can save months!

After DCA, “Appreciated trade” appears on 7/14/08 because the strike price exceeds the new position CB. Getting assigned at $17.50, in other words, would result in a profitable position. Note that in order to maintain a [$7.43] higher [than the stock] strike price, MacDuff sold an option six months out in time.

SNCR’s continual decline forces an “Interim trade” on 1/26/09 because the new strike price is less than the CB. Positions with interim trade status will result in loss if they end with assignment at the lowered strike. Because of this risk, interim trades involve selling short-dated options to allow less time for the stock to turn around and move strongly above the short strike.

Two BB & RO & Up adjustments were used to manage the bullish reversal in SNCR.

Finally on 6/11/09, the short call strike was raised to $15. While this is still less than the average stock price, it is greater than the position CB thanks to the series of credit trades. When SNCR was assigned at $15.00, this position made 18.76%.

Without the options, 100 shares posted a loss (from $23.03 to $15.19) and 100 shares posted a gain (from $10.07 to $15.19) resulting in an average return of 8.40%.

This would have drastically underperformed the CC position.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 32)

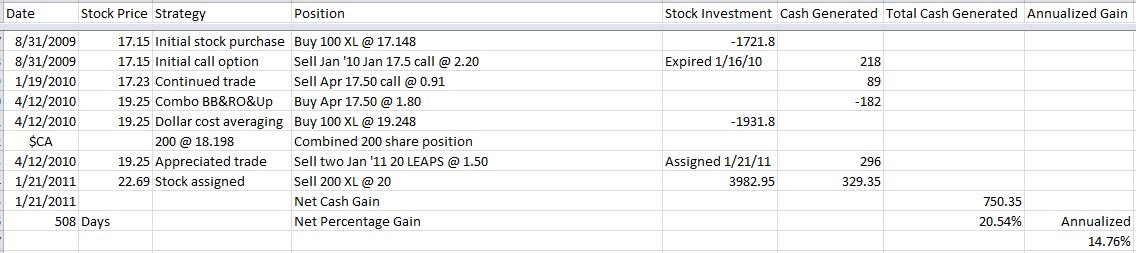

Posted by Mark on February 24, 2014 at 05:08 | Last modified: February 13, 2014 16:21Today I will analyze a Rich MacDuff example of the Combo BB & RO & Up position management strategy.

One thing I like to do is evaluate the CC/CSP performance against the stock. This position was held for 508 days and made 20.54%. The stock increased 32.30%. Since he bought more shares he would not have participated in the full gain. Half the shares would have made 32.30% and the other half 17.87% for an average of 25.09%.

While this is one occasion where I may not walk away with the warm fuzzy feeling of outperformance, consider some other things. First, the position made money at an annualized rate of 14.76%. I would be happy if my total portfolio returned that! Second, this would be one position among many during the course of a year. Some will return less and others will be supercharged. Ultimately, what I really want to know is how poorly the losers fare.

This position is interesting because it is not an instance I would have expected the Combo BB & RO & Up adjustment to be applied. The position was never losing money. Sans adjustment, the second option would have been assigned on 4/16/2010 for a gain of 17.83% vs. +14.99% for the stock. Why not simply take assignment and move onto the next position? If he wanted to stay with this stock then he could have initiated a new position at the higher stock price.

How valuable was the roll adjustment? Factoring in a $2/contract commission, I will calculate the annualized return of the roll:

(284 days – 4 days) / (365 days / 1 year) = 0.767 years.

The adjustment return is:

($1.75 – $0.34) / $17.148 = 8.16%

The annualized return is:

8.32% / 0.767 years = 10.64%

This is not great but acceptable–especially for a position he might be fighting to make/keep profitable. This one was profitable and handsomely so. The calculation helps me to better understand why the annualized return of the whole position was [marginally] subpar when the uptrending stock really posed little challenge at all.

My preference will be to reserve dollar cost averaging ($CA) for cases where I am forced to avoid a loss.

In the next post, I will talk more about the $CA adjustment.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 31)

Posted by Mark on February 21, 2014 at 04:44 | Last modified: February 12, 2014 06:57In the last post I described how to evaluate the value of potential adjustments. Today I begin discussion on another trade management technique called the Combo Buy Back and Roll Out and Up (Combo BB & RO & Up).

I previously made the points that trade adjustment is not risk-free and that we will encounter cases where a rolling adjustment cannot be found. In his book Systematic Covered Writing, Rich MacDuff describes this situation:

> Unfortunately, with an Interim Trade position there will be times

> when the SysCW Buy Back & RO & Up strategy will not work

> mathematically… the cash received for the Roll Out option would

> not be greater than the cash needed to close the existing option…

> there is a solution… the SysCW Combo BB&RO&Up strategy.

The steps for this adjustment are as follows:

1. Buy to close the existing short call.

2. Buy 100 additional shares of the underlying stock (this is dollar cost averaging or $CA).

3. Sell one more contract than was purchased in step 1 at a higher call strike than previous.

This adjustment should raise cash and increase the strike price.

MacDuff takes a shot at the Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options, which is a booklet published by the CBOE that all new brokerage clients must be provided. The booklet states:

> The writer of a covered call forgoes the opportunity to benefit

> from an increase in the value of the underlying… above the

> option [strike] price, but continues to bear the risk of a decline

> in the value of the underlyling…

MacDuff argues this to be false. The Combo BB & RO & Up adjustment allows us to benefit from stock appreciation. We only surrender this opportunity if we do nothing.

Here is an abbreviated example of this adjustment from the MacDuff archives:

I will discuss this further in the next post.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 30)

Posted by Mark on February 18, 2014 at 07:06 | Last modified: February 12, 2014 05:57The current discussion regards evaluating the value of a position adjustment.

Remember, the goal is to raise cash with every trade. Ideally, MacDuff would like us to raise cash at an annualized rate of 15% or more to ensure a profit of at least 15% annualized when the position is closed.

For a RO & Up short call adjustment, I take the net credit (debit) of the trade, add the decreased intrinsic value of the replacement option, divide by the cost basis, and divide by number of additional years sold. For example, suppose XYZ trades at $51.23, I have a short Feb(8) 50 call in place, and I can roll to the Jun(127) 55 call for a credit of $3.03. I have sold:

(127 days – 8 days) / (365 days / 1 year) = 0.326 years.

The adjustment return is:

($3.03 + $1.23) / $51.23 = 8.32%

The annualized return is:

8.32% / 0.326 years = 25.51%

That would be a valuable adjustment!

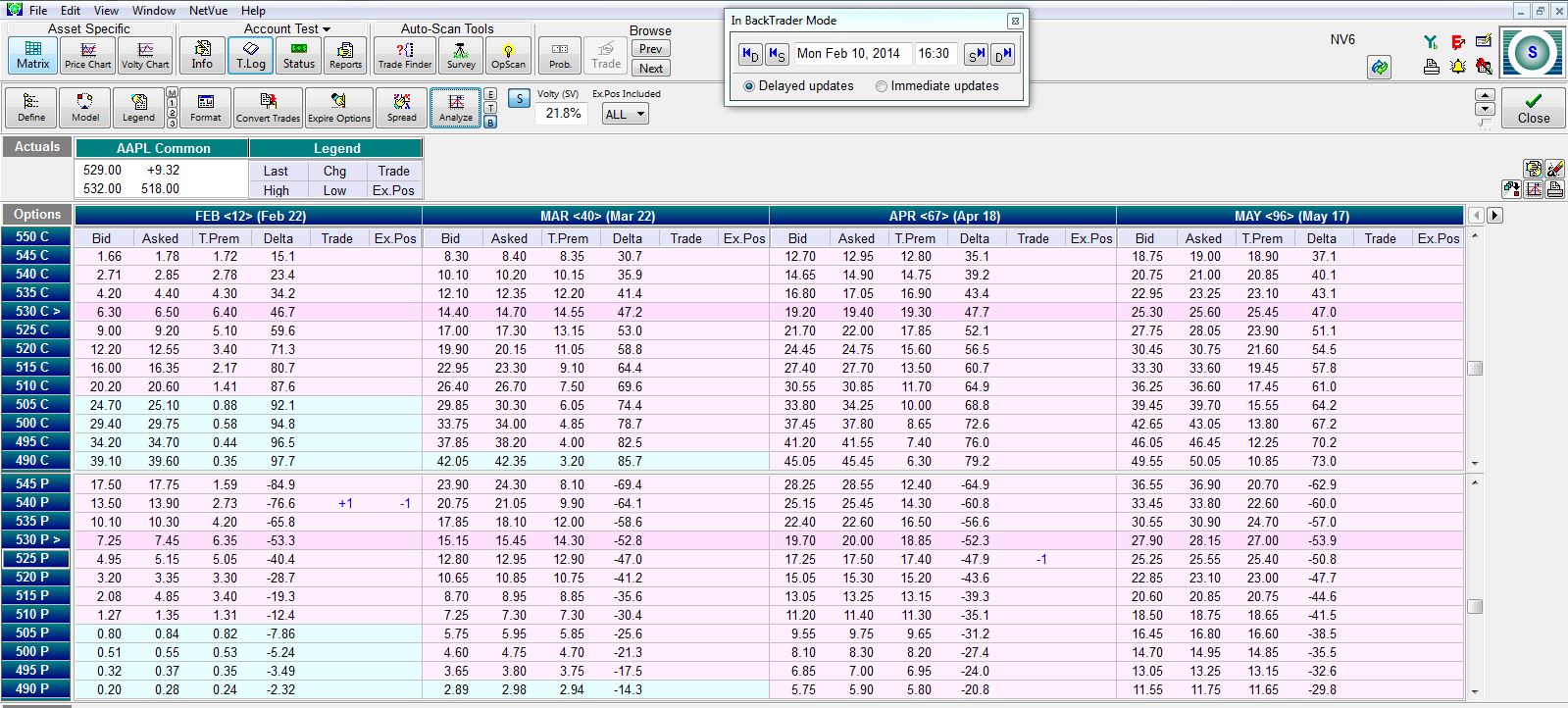

I can perform a similar calculation for a roll down and out put adjustment. For every point the stock price falls below the short put strike, I owe $1/share if assigned. If I can roll the CSP down then I basically take the decreased intrinsic value back into my pocket. This typically costs money, which I may be able to recoup by rolling the option out in time.

For example:

Here I am rolling out 67 – 12 = 55 days, which is 55 / 365 = 0.151 years.

The net credit on this trade is $17.25 – $13.90 = $3.35.

The decreased intrinsic value is $11.00, which makes the total return ($11.00 + $3.35) / $540 = 2.66%

Annualized return = 2.66% / 0.151 years = 17.64%

Once again, this is a valuable adjustment.

For Interim trades where short calls are rolled down, I can calculate the overall potential annualized return of the whole position to determine whether the adjustment is worthwhile.

For appreciated trades where short puts are rolled up, I can calculate the overall potential annualized return of the whole position to determine whether the adjustment is worthwhile.

A nasty situation occurs when the stock rallies sharply above a lowered short call strike (Interim trade) if the strike is below the current cost basis of the position. I will discuss this situation in the next post.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 29)

Posted by Mark on February 13, 2014 at 07:06 | Last modified: February 7, 2014 08:33Quick review: why bother calculating the annualized return of a RO & Up adjustment? Ideally, I want to raise cash with every trade. The initial trade should start with the potential to make at least 15% annualized. If each subsequent trade also makes at least 15% annualized then I will have an overall profit exceeding 15% annualized when the position closes.

Last time, the oft-mentioned theme of mirror image thinking got me out of a logical conundrum. I can, therefore, factor in the decrease of extrinsic value on a RO & Up when calculating the adjustment’s annualized return. What about with CSPs?

When a short put goes ITM, the profit is capped at expiration. Rolling down and out to lower the strike price therefore releases funds and makes them available. I should therefore be able to factor in the decrease of extrinsic value on this put adjustment when calculating the annualized return of the adjustment.

Issue resolved.

Evaluating whether to roll a short call down for a CC position or to roll a short put up for a CSP position is slightly different because the expiration month does not change. In this case I must calculate the annualized return for the whole position assuming it goes back to cash (i.e. call assigned or put expires) at expiration.

If rolling in the same month poses risk of being assigned at a disadvantageous strike price then my head needs to be on a swivel watching out for sharp changes in stock price and ongoing availability of replacement options for escape. If assignment at the adjusted strike price still results in a profitable position then it’s a choice with which I can feel comfortable.

In the next post, I will introduce the management technique of dollar cost averaging.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 28)

Posted by Mark on February 10, 2014 at 06:51 | Last modified: February 6, 2014 10:29Recall that MacDuff’s general philosophy is to raise cash with every trade. As my cash cushion continues to increase, eventually the stock will find a bottom and I will be able to exit the trade with a profit even if the stock has decreased over that time interval.

In the last post I showed a debit (i.e. cost money) adjustment and suggested the inclusion of the raised strike price when evaluating the adjustment. No I did not raise cash but raising the strike price to the stock’s current price essentially releases additional money, which is just as good as being paid.

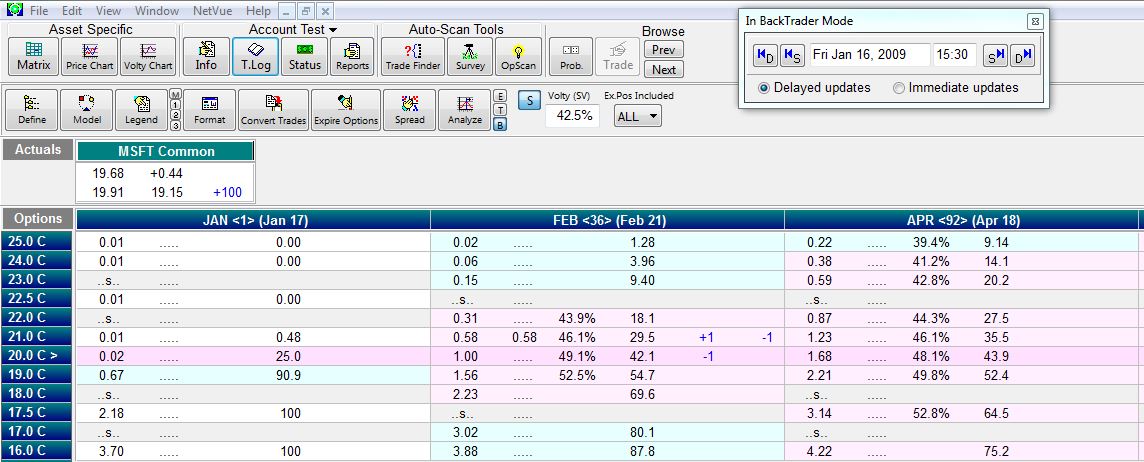

I run into difficulty with this argument when considering a lowered strike price. A stock falling enough to require a lowered strike price (i.e. “rolling down”) to collect additional premium is what MacDuff terms an “Interim trade.” If I include the raised short call strike to the return calculation then would I also encounter instances where rolling down should factor in the lowered short strike to the calculation? If I did that then most Interim trades would be debit trades. For example:

This adjustment buys to close the short Feb(36) 21 call and sells to open a Feb(36) 20 call. The net credit is $0.42. By lowering the strike price $1, though, I have an obligation to sell the stock for $1 less if I get assigned. Yes I brought in $42 by rolling down but I cost myself $100. This is a debit adjustment; why would MacDuff allow it?

Something seems amiss with this comparison. With the RO & Up adjustment, I changed expiration months. The time I sold allowed me to calculate an annualized return. Here I did not sell time and the return therefore cannot be annualized.

I think the resolution has to do with the mirror image thinking I discussed earlier. The comparison should not be between RO & Up and rolling down. The comparison should be between RO & up for a call and rolling down and out for a put.

I will continue this discussion next time.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (2) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 27)

Posted by Mark on February 7, 2014 at 05:29 | Last modified: February 3, 2014 07:33My last post included a backtested example illustrating why rolling is not a risk-free panacea for CC/CSP positions. Did the RO & Up adjustment for a debit truly violate MacDuff’s guidelines?

One thing I find debatable about the annualized adjustment calculations presented in the last post is whether to account for the change in strike price. One of MacDuff’s guidelines is that every adjustment should be done for a credit [ideally at a 15% annualized rate of return]. With MSFT at $20.99, I rolled the May(22) 20 call to Jun(57) 21 call for a debit of $0.24 (including commissions).

Usually when the RO & Up is performed, the strike price is moved OTM to reduce assignment risk. Because Nobody Knows whether the stock will reach the new strike at option expiration, I would not add the change to the return calculation.

In the MSFT example, however, the RO & Up adjustment moved the strike price from ITM to ATM. While I still agree that Nobody Knows whether the stock will reach the new strike price at option expiration, the stock is already there after the adjustment! More specifically, what I am adding to the return calculation is the difference in intrinsic value of the short call because this decrease represents money in my pocket right now:

-$0.24 (including commissions) + $0.99 = $0.75 on the roll for an additional 57 – 22 = 35 days. That amounts to an annualized return of 30.34%.

This seems like a useful rule of thumb by which to determine whether a roll is worth doing especially if the position is profitable. When profitable, the other possibility is to take assignment: “nobody ever went broke taking a profit”

If the position is underwater like the MSFT example, though, then MacDuff says we have no choice but to continue fighting because we should never lock in a loss. In that case, my goal is just to continue rolling out and/or up until the strike price exceeds the cost basis of the trade.

I will continue this debate in my next post.

Categories: Backtesting, Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 26)

Posted by Mark on February 4, 2014 at 07:02 | Last modified: February 1, 2014 06:05I left off discussing the risk of compounding loss when using the RO & Up adjustment. Today I will illustrate with an example.

This CSP position begins on January 29, 2008, by selling a Jul(132) $32.50 put on MSFT (trading at $32.55) for $2.28. The credit received provides 7.21% of downside protection and a potential annualized return of 19.40%. This satisfies my variation of the Math Exercise, which is to accept at least 5% of downside protection rather than MacDuff’s 12-15%. I have encountered great difficulty finding stocks that meet the latter criterion in addition to the 15%+ annualized return.

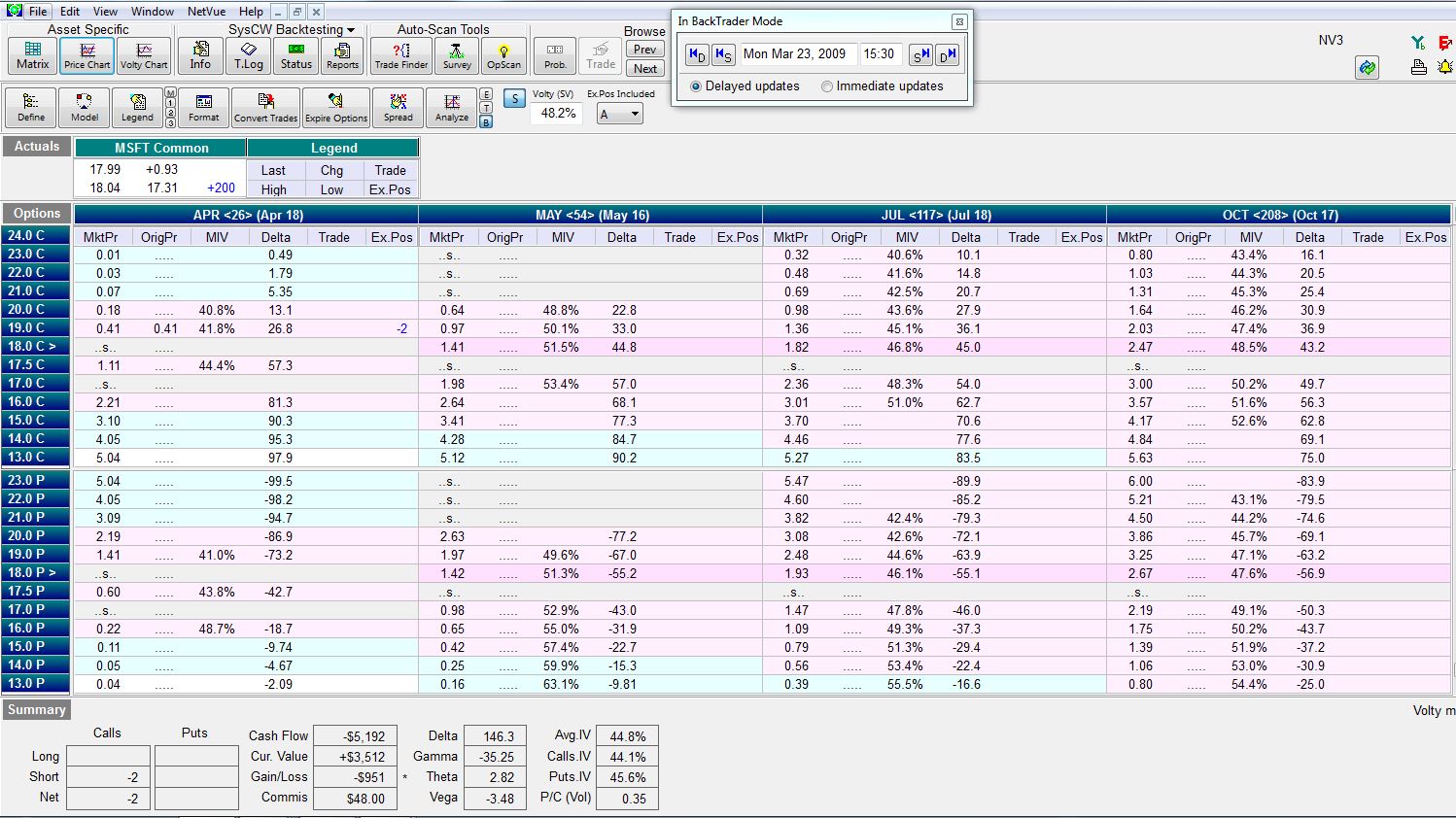

With the market in decline over the next 14 months, I took assignment of the shares and then sold CCs against the stock. I had to roll down three times through March 2009 expiration. On March 23, 2009, the stock chart looked like this:

On this day, I rolled down for a fourth time:

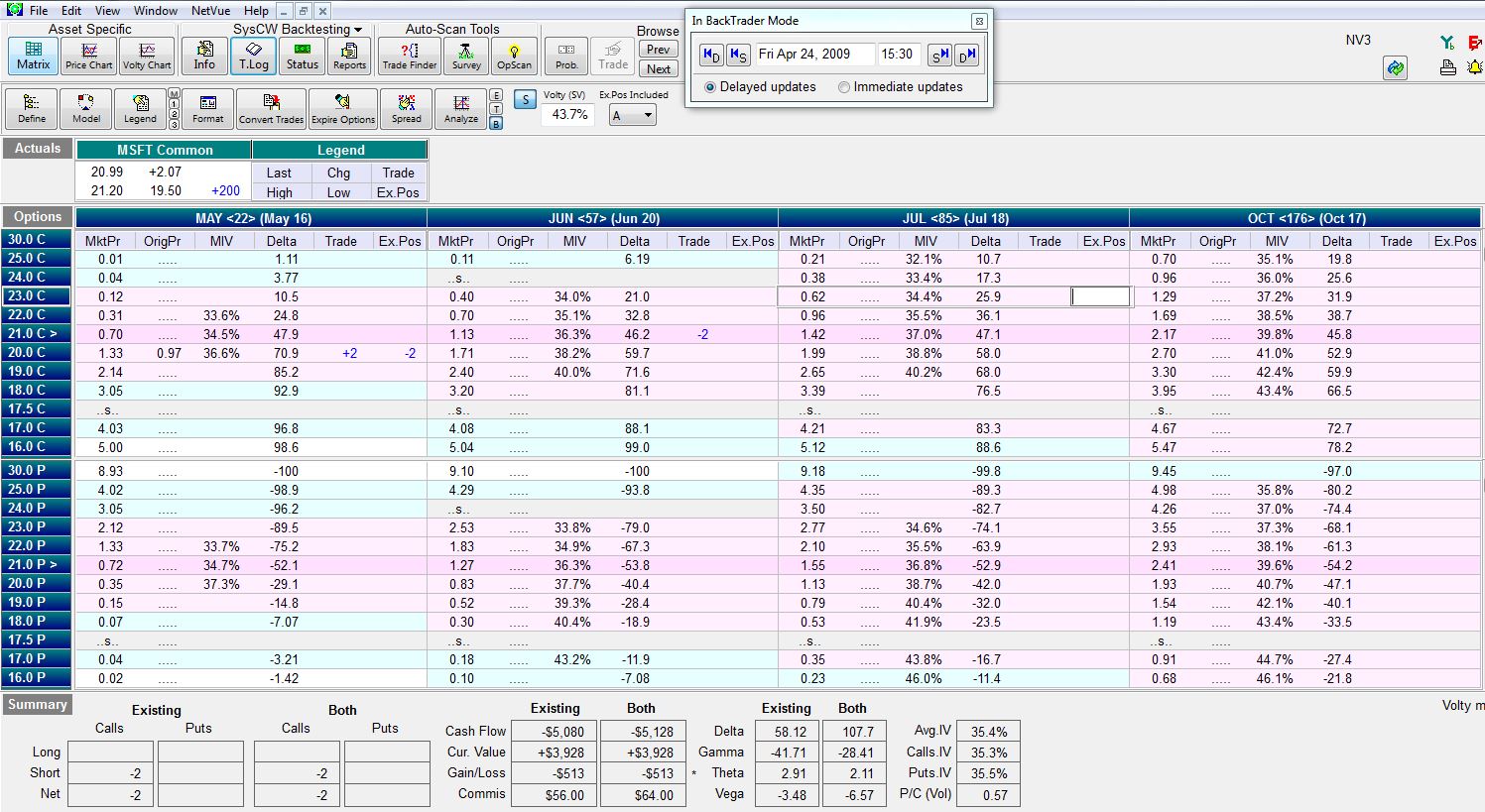

The stock had already found a bottom and over the next month, it moved sharply higher. On April 24, 2009, I made the following RO & Up adjustment:

The position is down $527 and I’m fighting to keep the short call OTM. With this trade, I bought back the May 20 call for $1.33 and sold the Jun 21 call for $1.11. I therefore spent money on this adjustment, which is a violation of the guidelines. Ideally I want to take in money with each adjustment at a 15% annualized rate of return or better.

What if I sold the Jul(85) $21 call for $1.42? The credit on this roll would have been $0.31. The annualized rate of return for this adjustment would have only been 6.87%, however.

What if I sold the Oct(176) $21 call for $2.17? The credit on this roll would have been $1.06 but the annualized return would have only been 9.62%. The longer-dated call would not decay as fast as the Jun or Jul call either. This means if the stock continued to rally then I could quickly run out of expiration months for rolling.

I will continue discussion of this example in my next post.

Categories: Backtesting, Option Trading | Comments (1) | Permalink