Covered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 37)

Posted by Mark on March 27, 2014 at 06:13 | Last modified: March 5, 2014 05:04I devoted the last four posts to discussion of the Martingale betting system because martingaling is to gambling what dollar cost averaging (DCA) is to investing/trading. Today I discuss incorporation of DCA to the CC/CSP trading plan.

The first step is to determine my maximum tolerance for loss. This is critical because I will approach that limit twice or four times as fast after doubling down once or twice, respectively. If I don’t know my maximum tolerance for loss–and most traders who have never experienced a volatile market and/or substantial loss do not–then the safest advice is probably to assume my tolerance will be small and to avoid doubling down altogether.

For the more experienced trader who is willing to commit additional capital, the next step is deciding when to DCA. The only recommendation MacDuff offers for this is “when a stock is on sale.” He seems to DCA inconsistently in his archives of successful positions.

Unfortunately, determining when a stock is “on sale” can only be done in retrospect. Any stock that went bankrupt was first down 10%, 50%, or more. Any of those levels could be considered “on sale.” Such identification might later be revised with the classification “falling knife” and dire regret had I acted and committed additional capital at the higher stock price. This is the risk of DCA and we can never get around it.

When to DCA is therefore an individual decision that must be made in accordance with your risk tolerance. Perhaps you will elect to DCA when the stock falls 30% or 50% or more. Perhaps you will do some backtesting [with a survivorship-free database] and decide what best fits your sample. I don’t have an answer to this question and I don’t think a correct answer exists. Period.

I will continue with more DCA discussion in my next post.

Categories: Money Management, Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkThe Tall Tale of Martingale (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on March 24, 2014 at 06:59 | Last modified: February 27, 2014 07:25Given unlimited capital, a Martingale betting system is guaranteed to make money because no matter how extreme the losing streak, at some point I will win. Casinos employ two additional tactics to make sure this does not happen.

I have described at length how large the next bet can become relative to the initial bet during an extreme losing streak.

If this doesn’t sound dire enough already, here’s the kicker in the world of Vegas: even if I have enough money to cover the next double, at some point I will not be allowed to. On a $5 [maximum payout] table, for example, casinos will usually limit the maximum bet to $500-$1000. After eight consecutive rounds of bad luck, I will no longer be able to recoup my losses with the next bet. I might therefore have to win two consecutive games with large bets to end up net positive.

Probability of profit decreases markedly if I must win multiple times in a row to recoup my losses.

The martingale gambler is targeted further by casinos that also raise the minimum bet. Martingaling relies on the number of times I can double while still remaining within table limits because I am always less likely to lose (n + 1) consecutive times than I am to lose n times in a row. I could simply play at a table with a larger maximum bet except typically the minimum bet is proportionally larger as well. This maintains the same number of betting doubles before table limits are reached.

Here’s the bottom line: if I lose enough times in a row with a Martingale betting system then I will go broke and not have enough money to continue or I will reach the table limit. While martingaling can work in the short term, the longer I play the more likely I am to encounter an extreme losing streak forcing a meeting with my demise since I will be prohibited from raising my bet high enough.

In Vegas and on Wall Street, there is no free lunch despite an occasional illusion to the contrary.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (0) | PermalinkThe Tall Tale of Martingale (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on March 21, 2014 at 06:41 | Last modified: February 27, 2014 06:57Here’s a brief review of what I have discussed with regard to Martingale betting systems.

Although rare, extreme losing streaks most definitely occur. Martingale betting therefore favors shorter playing times because the longer I play, the more likely I am to encounter an extreme losing streak.

Martingale betting systems involve doubling my bet every time I lose. A long losing streak could easily have me down over $10,000 from a $5 initial bet.

Most people could never tolerate facing a loss that is orders of magnitude larger than the potential gain. If this has never happened to you then consider it extensively before attempting a trading system that carries a large potential drawdown.

I’ll go one step further…

If this has never happened to you then I strongly suggest assuming you would not be able to tolerate it either! Find another trading system or position size the system very small to prevent a heavy drawdown from significantly denting your total net worth. The alternative is learning something about yourself at the worst possible time: when you exit a trading system only to realize a catastrophic loss of capital.

Unfortunately, this has happened to me.

Would you ever stand being down over ten grand with the hopes of ending up five bucks? Most traders and investors cannot sleep at night or deal with the anguish of losing so much money when they stand to make so little even though they are one win away from vaporizing the entire loss.

Does that make us weak? Yes but no: with every additional loss, the huge loss I face doubles again! Maybe getting out with a few bucks to my name is better than losing absolutely everything.

In my next post I will describe a couple other ways casinos stack the deck against Martingale betting systems.

Categories: Money Management, Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkThe Tall Tale of Martingale (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on March 18, 2014 at 07:07 | Last modified: February 26, 2014 08:48In the last post I mentioned, “while rare, extreme losing streaks do occur.” This is an important detail worthy of extra time.

One of the best bets in a casino is found in the game of Craps. The table I presented in the last post assumed even money bets, which are very hard to find in the real world. Casinos make their money on the house edge. Betting the pass line in Craps offers a 49.29% probability of winning, which translates to a low 1.41% house edge.

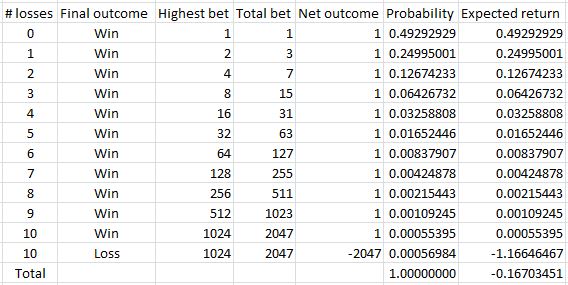

Consider a simple Martingale betting system with $1 as the standard bet. Suppose I have $2,047, which can cover up to 10 consecutive losses. Here is a table of outcomes:

Looking at the probability column tells us just how rare those extreme losing streaks can be. The chance of five consecutive losses is about 1.6%. The chance of 10 consecutive losses is 0.055% or one out of every 1818 times. The chance of being struck by lightning (based on number of people hit each year) is one out of three million. The odds of winning a million dollar lottery are roughly one in 10-12 million. Compared to these numbers, then, the odds of 10 consecutive losses are pretty good!

How scary is that?

That there is any chance of an extreme losing streak means the Martingale betting system favors shorter play over longer play. The longer I play, the more likely I am to encounter such a losing streak. If I knew how many rolls per hour occurred in a particular Craps game then I could calculate the odds of experiencing one based on playing time.

Regardless of duration, the ultimate arbiter of whether I will “live to play another day” lies in the hands of Chance.

I will write more on Martingale betting systems in the next post.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (1) | PermalinkThe Tall Tale of Martingale (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on March 13, 2014 at 06:07 | Last modified: February 21, 2014 05:34Dollar cost averaging (DCA) appears to be a panacea based on Rich MacDuff’s position archives. To best explore the risk and downside of DCA, I’m going to borrow from the world of gambling and explore the Martingale betting system.

Martingale betting systems date back to 18th century France.

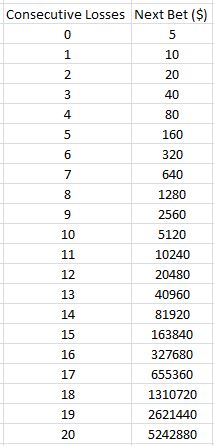

The typical Martingale betting system works as follows. Start by making a standard bet on a [roughly] even-money gamble like red in roulette or Tails on a coin flip. If you win then repeat the standard bet. If you lose then double your previous bet. After a series of losers, when next you win your net profit on the series of games since the last win will be the standard bet.

Let’s go through a Martingale example. Suppose I bet $5 and win. I bet $5 again but this time I lose. Next I bet $10 and I lose. Then I bet $20 and I lose. Sticking to my system, I then bet $40 and I win. Two winners (in five attempts) and I am up $10. As long as I can double my bet after losing, I am guaranteed to come out ahead when I win.

Unfortunately, in real life I cannot always continue to double. One reason is because at some point I will likely run out of money. While rare, extreme losing streaks do occur. If I lose 11 consecutive games as described above then…

…I will have to risk $10,240 for the next bet. If I cannot afford that, then I will realize a $10,235 (minus the number of wins multiplied by $5) loss.

Do most people even have ten grand when they walk into a casino? I would probably need a briefcase or a big duffel bag to carry that around and that would make me nervous! I’d probably want a security detail to avoid being robbed.

I will continue this discussion in the next post.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 36)

Posted by Mark on March 10, 2014 at 03:08 | Last modified: February 21, 2014 04:56Today I want to get back to discussion of dollar cost averaging (DCA) as a position management technique and its implications for risk management.

In his book Systematic Covered Writing, Rich MacDuff writes:

> …the disadvantage of using the [DCA] strategy

> stems from the possibility of further price

> erosion of the stock after a second purchase.

> This sets up the possibility of [DCA]…

> a second time.

Just how much more capital should I be willing to commit to a position as it goes against me?

Without defining this number, I cannot know how much cash to keep on the sidelines in case I need to use it. If this is unknown and I am willing to repeat the DCA process then I am playing a game of unlimited risk. I may go months to years without ever realizing this or thinking this way because such a string of bad luck may come around once in a blue moon. Nevertheless, when that “blue moon” or “black swan” does show itself, I am a prime target for getting blown out of the water… maybe never to trade again.

Keeping money on the sidelines also complicates the matter of calculating returns. Recall the last post where I derived the possibility of having to make 3,432 trades in one year. That involved trading the whole account. The total return of the account drops proportionally to the percentage of cash I keep on the sidelines, though. The 15% annualized return MacDuff frequently writes about becomes 9-12% annualized if 20-40% of the account, respectively, sits on the sidelines in cash for use toward DCA when [or if] needed.

In my next post I will borrow from the world of gambling to further study the pros and cons of DCA.

Categories: Money Management | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 35)

Posted by Mark on March 7, 2014 at 06:06 | Last modified: February 20, 2014 05:54Before I continue the discussion of dollar cost averaging (DCA) as a position management technique, I want to present a disclaimer about my previous discussion of annualized return.

In general, the sooner CC/CSP positions go back to cash, the higher the annualized returns. Especially for positions that last less than one month, MacDuff notes:

> As always it is VERY important to realize that in order

> to actually achieve the calculated gains, one would need

> to successfully repeat similar transactions over the

> course of twelve months.

This particularly applies to weekly positions, which are becoming more popular with traders. A position that makes 1% in five days has generated an annualized return > 50%.

How can I realize this return on my whole portfolio?

First, since it is a 1-week position I must repeat the trade 52 times.

Second, if each position puts 1.5% of my portfolio at risk then I need to do about 66 of these trades at once.

At the very least, I’m looking at 52 * 66 = 3,432 trades per year.

That does not include positions that will have to be adjusted or manually closed, either. Unless I am willing and able to be sitting at my computer full-time during market hours, this is probably unrealistic.

What is more realistic might be to allocate a segment of my portfolio to weekly and “short-TERM” positions. I can recycle these frequently and book some supercharged returns in this segment while limiting trading frequency to something my time schedule and attention span can accommodate.

The bottom line here suggests I should continue to use annualized return as a guide to initiating and adjusting positions because this provides an apples-to-apples comparison regardless of position duration. I can be enthused about exceedingly high annualized returns–but not because I would ever expect to realize such a return on my whole portfolio. Rather, supercharged positions may serve to offset the periodic longer-term positions that will drag on for years.

The latter seems to be an unfortunate reality of CC/CSP trading just as “dogs” are an inevitable part of stock investing.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | PermalinkCovered Calls and Cash Secured Puts (Part 34)

Posted by Mark on March 4, 2014 at 04:23 | Last modified: February 18, 2014 13:24Before I continue the discussion of dollar cost averaging (DCA) as a position management technique, I want to expound on a statement I made that gets at the core of CC/CSP trading.

Recall from my last post:

> DCA lowers the cost basis… over 28%, which leaves

> $6.48 less to recoup for position profitability. This

> can save months!

The goal of these positions is to have the short call be assigned (CC) or to have the short put expire (CSP). Once this occurs then the margin requirement is released and a new position may be initiated in its place.

Annualized return is about dividing total return by the number of years in trade. The shorter a position lasts, the smaller the denominator and the greater the annualized return.

Lowering the CB, which DCA allows us to do, decreases how much cash we need for breakeven or for position profitablity. Once profitable, I always want to keep an eye out for position exit via option expiration (CSP) or option assignment (CC). This effectively locks in my gain and allows me to move on.

The sooner I can end a position, the greater the annualized return. A core mantra of the CC/CSP approach is “back to cash, back to cash, back to cash!” In general, positions that take a few months or less can post juicy annualized returns (18-30%+) while positions that drag on for years score annualized returns in the single digits.

If single-digit annualized returns is the worst-case scenario then we’re looking at a trading approach with tremendous potential! Realize too that this will tend to occur when stock price tanks resulting in vast outperformance by the CC/CSP.

Unfortunately, I suspect the worst-case scenario is more likely to involve corporate bankruptcy, a relentless stock decline, or a sudden stock crash. If I only see this on 1 out of 1000 positions then I can comfortable absorb that loss. If I see this on 1 out of every 10 positions, however, then my optimism would suffer a substantial blow.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (1) | Permalink