Against Target Date Funds (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on September 29, 2016 at 07:33 | Last modified: August 9, 2016 11:56I previously discussed two articles in the June 2016 AAII Journal arguing against target date funds (TDFs). Charles Rotblut, CFA, (AAII vice president and editor) wrote a third article in the same issue that takes aim at TDFs.

In the article, Rotblut samples six different TDFs. He discusses the importance of speed to final allocation:

> The Vanguard fund will reach its final allocation

> by 2027, versus 2030 to 2039 for the Fidelity

> fund. A shorter glide path and a larger

> allocation to bonds… may be a plus for

> someone with a shorter expected life span and/or

> greater cash needs in retirement… The ideal

> strategy provides a person the right amount of

> money to fully fund retirement and no more

> beyond what is desired to be bequeathed.

Rotblut says target date depends on expectations for other retirement income that may ease the burden on your nest egg:

> For example, say you plan to retire in 2020… if

> you do not expect to be reliant on your portfolio

> for retirement income—thanks to a pension or

> other sources of income—you could choose to go

> with a 2025 or later-dated fund instead. A

> later-dated fund will give you a greater

> allocation to stocks at retirement and thereby

> more long-term growth. On the flipside, if you

> don’t think you will be able to withstand a bear

> market near your retirement date, you should

> consider a shorter-dated fund.

Rotblut concludes by suggesting creation and management of one’s own portfolios:

> Setting aside questions about whether TDFs use

> the most optimal allocation strategies… the

> biggest downside to them is the lack of

> customization. Shareholders in these funds

> are locked into specific fund families. They

> are also locked into allocation ranges based

> on planned retirement ages.

I think his most damning critique of TDFs comes near the beginning of the article where Rotblut shows a lack of clear consensus on capital allocation. Six funds with a target date of 2020 have a current allocation of stocks and bonds ranging from 38-65% and 30-59%, respectively. Final fund allocations for stock and bonds range from 20-30% and 46-80%, respectively.

How much of a leap is it to suggest I might as well put on a blindfold and take aim at a dartboard?

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | PermalinkAgainst Target Date Funds (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on September 27, 2016 at 06:40 | Last modified: August 9, 2016 11:13At the second local Fintech Meetup a couple months ago, we had a presentation by a startup company (name omitted to protect the professionals) selling target date funds (TDF). The entire presentation begged the question: why bother?

Wikipedia describes a TDF as a collective (e.g. mutual fund or collective trust fund) investment scheme offering a simple solution by gradually shifting the portfolio to a more conservative asset allocation by the target date (usually retirement).

Intended as constructive criticism, I suggested the presenter do some backtesting to demonstrate that TDFs are better than conventional vehicles.

The very next day, I read my June 2016 American Association of Individual Investors (AAII) Journal and found three discouraging references to TDFs. The first reference was an interview with Jane Bryant Quinn: a nationally known personal finance writer/commentator. She concluded the interview with:

> I think the research shows that if you reduce

> the amount you hold in stock—you reduce the

> stock amount and increase the bond amount

> every year starting at 65—that is the least

> optimal way to make your money last for 30

> years. At least hold steady.

I viewed this as the weakest challenge to TDFs, which decrease equity allocation over time starting from a much younger age. Quinn cautions doing this from the age of 65 onward.

James Cloonan, however, suggests in a second article that Quinn’s comments are relevant to TDFs. Cloonan is the founder and chairman of AAII. He said:

> I hope there’s been more emphasis on keeping

> more in stock even at older ages or closer

> to retirement. In a recent interview in

> the AAII Journal… Quinn amazingly started

> to show the importance of doing this, and

> she’s a very conservative person. She

> pointed out that you just have an awful lot

> of your life ahead at retirement. You have

> to be a long-term investor if you’re going to

> make enough to keep up with inflation.

Indeed, Cloonan is largely against the idea of TDFs. He argues the conventional belief of increasing exposure to bonds as one gets older is completely flawed:

> One rule of thumb has been that the amount

> you should have in stock is 100 minus your

> age. Well, people retire at 70 these days.

> That means only 30% of their portfolios

> should be in stock. And they’ve got 30

> years to go. Bonds and cash may not even

> keep up with inflation. I think that is

> real risk.

I will continue with the next post.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (1) | PermalinkAm I Worthy of Self-Promotion? (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on September 21, 2016 at 07:39 | Last modified: February 3, 2017 09:35I feel grateful to have survived 9+ years trading full-time for a living. Do I have a successful story worth sharing? I dare suggest that I do.

In the last post I attributed some of my success to start-up capital available to help me through the learning years. That money did not just fall into my lap. I generated that capital by negotiating a respectable wage and studying to accrue investing knowledge. I put in the time to work and the time to learn. I put myself in a better position to start a business.

I also deserve credit for having the guts to leave a corporate job, which was stable income for me. It’s more complicated than “no risk, no reward” and for those who do take the risk and subsequently succeed, accolades should follow.

Plenty of people work in the trading industry but most are selling trading services or “education.” I am here to say you don’t need to pay thousands of dollars for such offerings. Rely on yourself. Work hard to earn start-up capital and take it from there.

As a successful entrepreneur since 2008, I have been selling myself short over the last few years but none of this means it’s simply “game over.” I still need to maintain my efforts with strategy development and trading my system. Every day I need to be aware of the risk I take because it could all evaporate in a heartbeat. Although much of what I have is due to my own hard work and discipline, I will continue to be grateful for what I have each and every day because things outside my control have not blocked my achievements.

Categories: About Me | Comments (0) | PermalinkAm I Worthy of Self-Promotion? (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on September 19, 2016 at 06:59 | Last modified: November 9, 2017 09:25I have traditionally avoided self-promotion or any activity attracting attention to my successes. In the last post I began to develop a case for why I do have a story worth telling about my trading business.

The oft-quoted statistic suggests 80-90% of all traders lose money. I have talked with a lot of traders over the years and only a couple have claimed to be trading for a living and making enough money to fully support themselves. Other industries have similar stories. The “mom-and-pop pharmacy” is an endangered species these days with the success of big chain pharmacies like Walgreens and CVS Health. How many lawyers advance to partner status? How many physicians have their own practices? The rest work for someone else and this includes the vast majority of engineers, teachers, and professors.

If survival as a tradepreneur puts me in the 80th-90th percentile then I am one who should be traveling to different investment clubs and groups across the country sharing my story about successful trading as a business. Starting with the advantages of options over stock and the necessity to understand discretionary versus systematic trading, my approach is somewhat unique.

One essential component that I believe has contributed to my success was the ability to save up start-up capital. This was provided by my job working pharmacy while I continued to pay student loans and a home mortgage. I negotiated a solid wage for myself and worked many overtime hours.

Stock investing also contributed start-up capital for my trading business. I have traditionally said that I was one of many to get lucky with my stock investments thanks to the bull market of 2004-2007. I did have that understanding of investing, though. Dad gets lots of credit for this because he initially spurred my interest in elementary school. I later went on to learn about stock screening. My statistical coursework taught me about models and curve-fitting, which probably put me in a better position to pick stocks that would later become big winners.

I believe having ample start-up capital to survive the lean, early years is the best way to start a business. Every business has a learning curve and very few entrepreneurs can expect to generate consistent, plentiful income right away. Without start-up capital, the added pressure to profit in order to afford basic needs is probably enough to crush most dreams of escaping Corporate America.

I will finish with the next post.

Categories: About Me | Comments (1) | PermalinkAm I Worthy of Self-Promotion? (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on September 16, 2016 at 06:30 | Last modified: February 3, 2017 09:36Much of the background for today’s post was written here and here. Perhaps because my Dad dislikes attribution of my current professional status to luck or everyday trading strategies, casual reflection had me reviewing this idea once again. For the first time, I am starting to entertain the possibility that I am a success story worthy of self-promotion.

I have traditionally shied away from advertising or marketing my triumphs. More than shy away, even, I typically run away. I’m a believer in karma and I think arrogance is a trap to which we humans often fall prey. The moment we get too overconfident or arrogant is the moment we get stricken down—often solely a result of our own sheer folly. I may be exaggerating a bit but I do believe it happens quite often.

I believe Nassim Taleb’s Fooled by Randomness teaches some important lessons about trading. People often get lucky and have transient success. I would hate to start advertising such success at a time when harsh reality was just about to set in. I would only be able to look in the mirror and say “you got what you deserved” if I were to misjudge temporary, random success for a long period of developing skill through hard work.

Having acknowledged my caution toward arrogance and the possibility of fluke, I do believe I deserve an objective assessment just like anyone else. As I step back and take a broad perspective, what do I see?

The most significant observation is that I am currently in the ninth year of operating a successful trading business. I started out working 60+ weeks for the first few years and so far that hard work has paid off. I do all the trading and devise my own trading strategies. I supervise myself. I work from home. I have a flexible schedule. I can trade on the road while hardly missing a beat.

Perhaps anyone working as a successful entrepreneur has a story worth telling because it is such a rare occurrence. I only know a couple people who are running their own successful businesses. Many people have jobs they dislike. Many people live paycheck to paycheck. Many people are chronically burdened by job-related emotional and physical stress. None of these, thankfully, apply to me.

I will continue this in the next post.

Categories: About Me | Comments (2) | PermalinkOptions are Better than Stock (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on September 13, 2016 at 06:48 | Last modified: July 28, 2016 15:40I feel I have done a pretty good job of establishing that options are better than stocks for most investors. One exception might be bullish speculators.

I previously demonstrated option outperformance when the stock moves lower, sideways, or moderately higher. I also made a strong case that options provide more consistent returns.

I previously suggested that options are inferior with regard to bullish speculation but I actually believe the opposite. If someone tells me up-front her goal is speculation then I would make the case for option leverage. “Swinging for the fences” is pretty much synonymous with buying options!

While no one option strategy is better in all market environments, given any market environment one can come up with an option strategy that should outperform.

For the average investor trying to build a nest egg for retirement, I have made a strong case for options as the superior way to go. One may worry naked puts/covered calls are limited-profit vehicles but I would ask how often it happens that the market runs away to the upside? This could be backtested. Even if this happens enough to result in lower annualized returns, the greater consistency of option performance likely makes up the difference. Besides, speculation (i.e. gambling) has no place in building a nest egg.

I did an internet search for “why don’t financial advisers use options” and found one enlightening response:

> You’re right to ask what the average financial

> adviser (FA) knows about investing… But, I

> think you’re underplaying a few additional points.

> First, that most FAs don’t have options

> registrations — so options aren’t even in their

> world view…

Advisers as fiduciaries are bound to act in the clients’ best interests. In my opinion, if they cannot do this because they lack “registrations” then they simply should not be in the business. If advisers cannot do this because they lack proper option education then that is even worse.

> Second, in this era of “low cost advisory” many

> clients are on active missions to cut their

> costs — expense ratios, trading fees — and make

> no mistake, but any active option overlays are

> going to have associated, non-trivial costs.

I would argue stocks and options to be comparable with regard to transaction costs. Given the proper know-how, any adviser can do either without significant material cost.

Bottom line: options options options, folks! This may be just what the industry needs to cure itself of the subpar returns people have been conditioned to expect and accept.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | PermalinkOptions are Better than Stock (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on September 9, 2016 at 06:42 | Last modified: August 4, 2017 08:20I believe I am already done if I were simply trying to argue that options are less risky than stock.

I have shown the naked put position to outperform long stock if the underlying trades down, sideways, or up “a little.” In the previous example, AAPL stock could trade up over 10% in one year and still lose to the naked put. I also argued for higher consistency of returns with naked puts over long stock. This means lower standard deviation of returns and lower volatility of returns. In this case, it also meant lower maximum drawdown for the option position.

All this suggests option strategies are a better choice for a large segment of stock investors. Options are more suitable for growth investors. Options are also more suitable for income investors given the non-refundable premium collected up-front.

I would say neither options nor stocks are suitable for “safety investors” who are most concerned with capital preservation. This may include the elderly and people in retirement. This does include the extremely risk-averse. For this group, Treasuries, highly rated corporate bonds, or certificates of deposit would probably be a better fit. I think the option position can lose less than the stock position but when the market gets really ugly both can lose significantly.

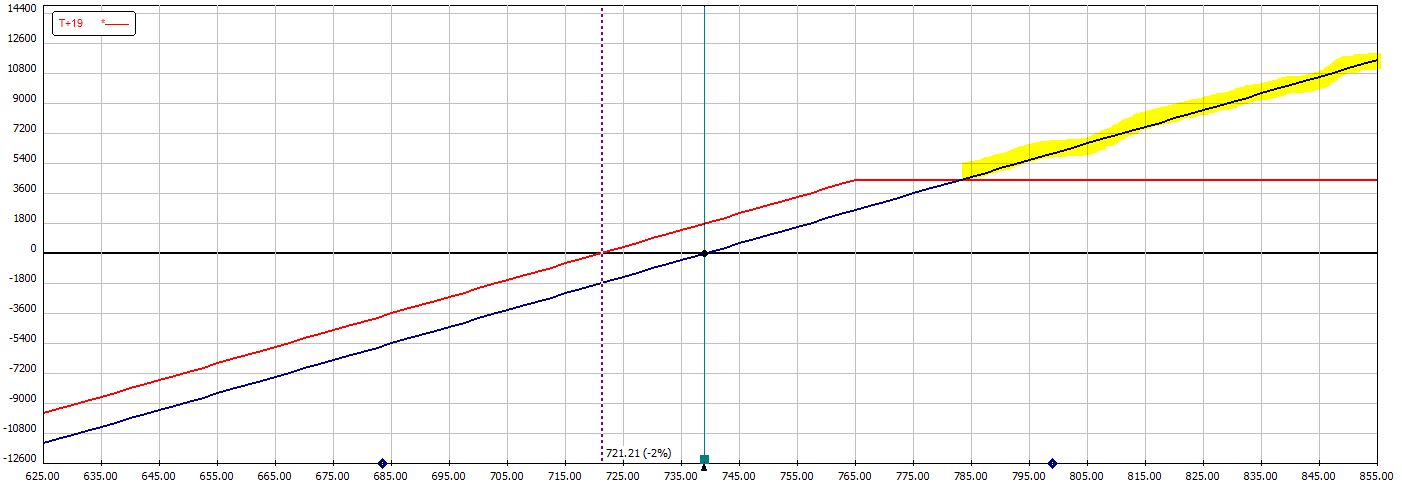

The one category more suitable for stock than options would seem to be speculation. This involves stock selection with the hope of hitting a home run rather than singles and the occasional double. In the following graph, the blue line represents long stock and the red line represents a covered call position:

The yellow highlighting indicates that when the market races higher, the stock can outperform. The option position has limited upside potential whereas the stock has unlimited upside potential. This is a reason why many people like to buy stocks. For some it is like the lottery: people hope to see their shares double, triple in price—or more.

I could argue that options (e.g. long calls) also outperform stocks to the upside. Unfortunately, though, I cannot implement options in such a way to outperform in bearish, sideways, and mildly bullish conditions and also outperform in strongly bullish ones. And if I implement options to outperform in strongly bullish conditions then I would underperform were the market to trade slightly higher or sideways (although I would outperform were the market to move significantly lower).

I will wrap all this up in the next post.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | PermalinkOptions are Better than Stock (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on September 8, 2016 at 05:06 | Last modified: July 26, 2016 11:16As discussed in Part 1, I have taken a defensive posture on the stock versus options debate in the past. As seen in recent articles by Perry Kaufman and Craig Israelsen, today I am going to implement a more anecdotal approach. When studied this way, options very much seem like a better trading and investment vehicle than stock.

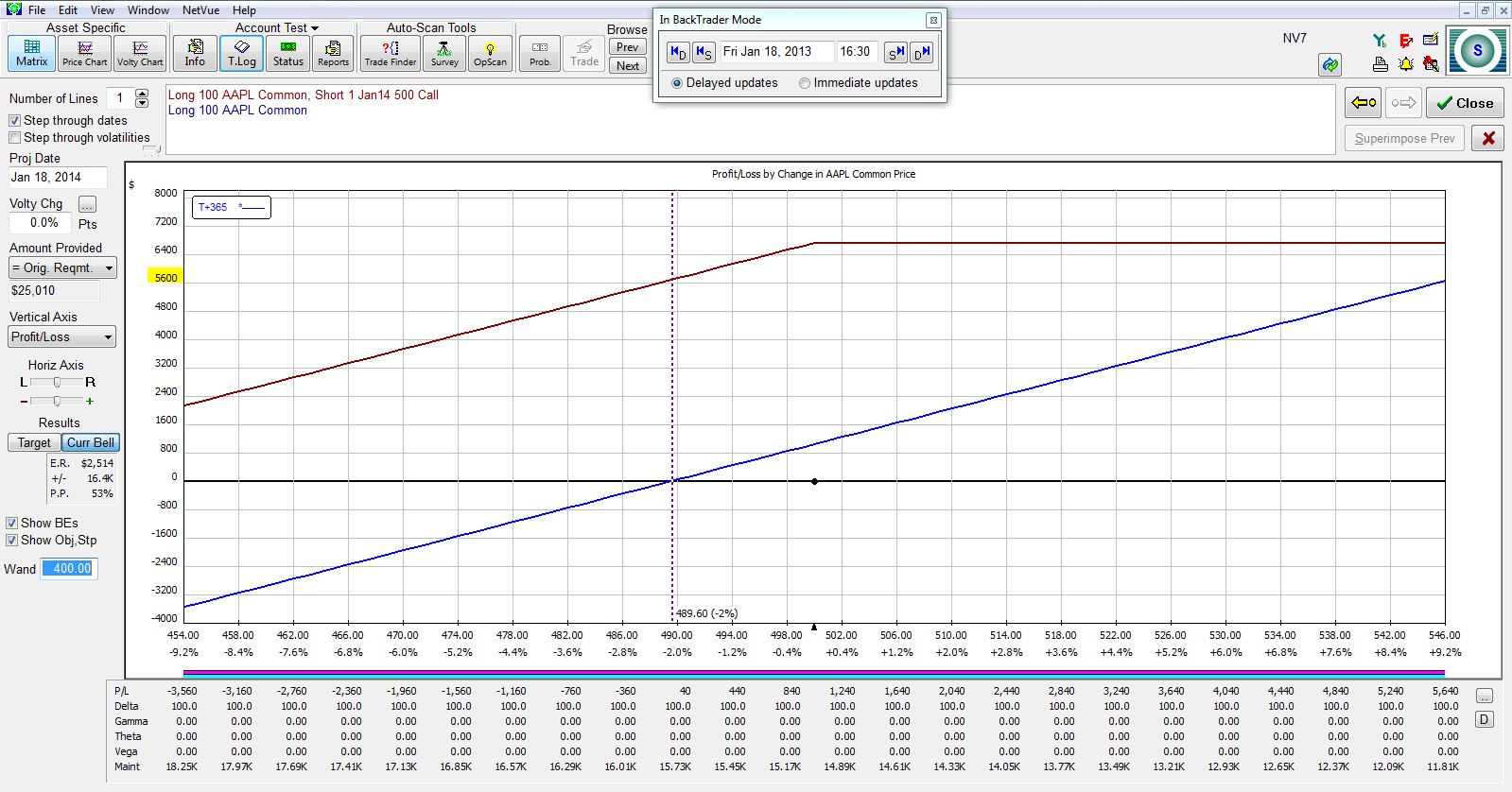

First, let’s revisit my comparison of long shares versus a covered call (CC) position from a 2013 blog post. The following graph plots the PnL of AAPL stock (blue line) and a CC position (purple line) 365 days after trade inception when the option expires. Stock dividends ($1,040) are included:

The vertical, dotted line shows breakeven for the stock position after 365 days if the stock price falls. At this zero profit level, the CC shows a profit of $5,600, which is the profit from selling the call at trade inception. The CC also outperforms farther to the downside and to the upside through an underlying price increase of over 10%.

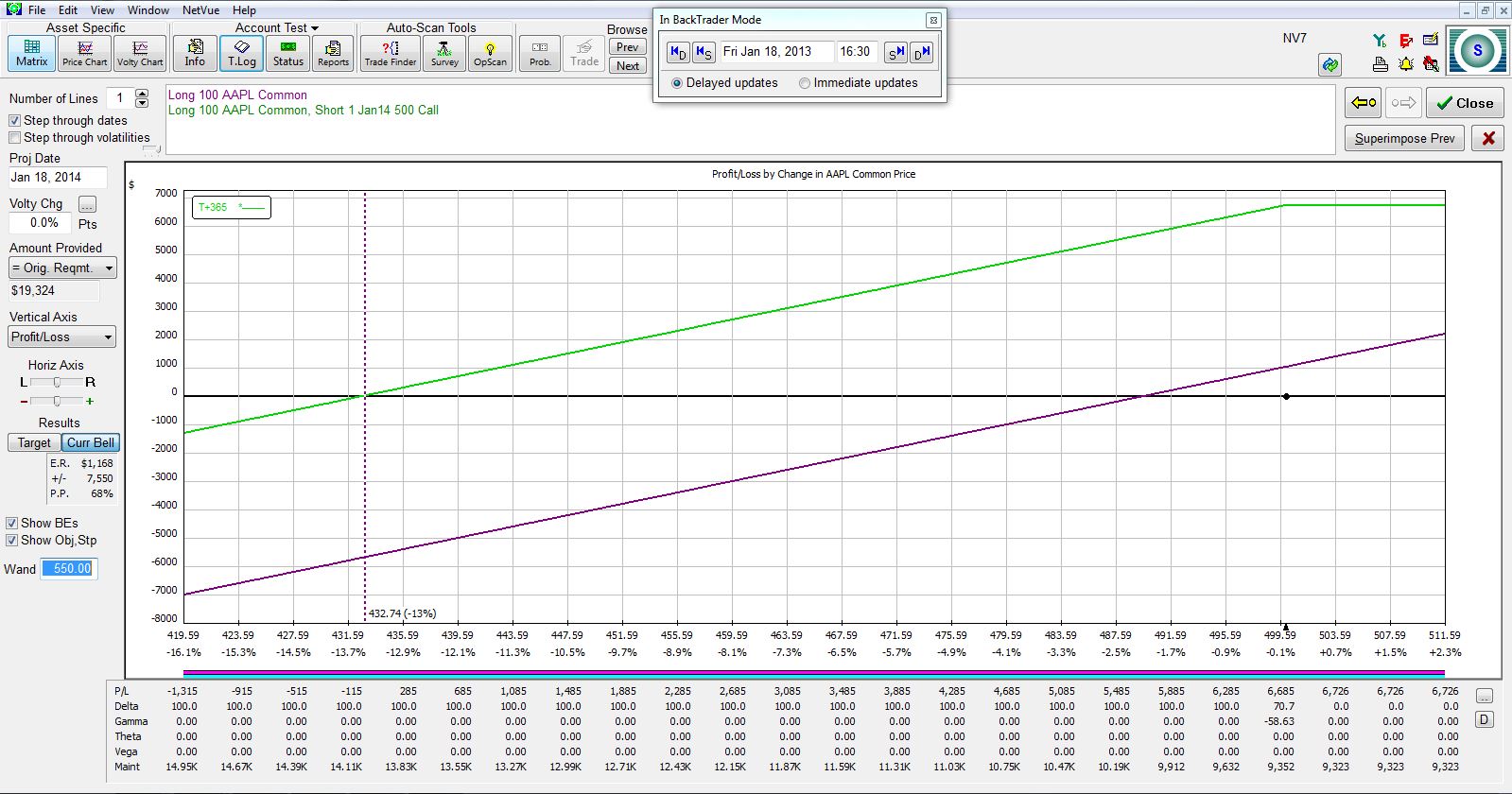

Second, I refer to the common interpretation of risk as potential maximum loss. To compare these positions when the market falls, we can shift the graph to the right:

The CC outperforms by the $5,600 mentioned above and this difference persists to a stock price of zero because the CC owner collects that non-refundable premium at trade inception.

Third, although a CC includes long stock, derivatives theory dictates that a CC is synthetically equivalent to a naked put. I illustrated this with graphs shown here. This is not anecdotal: this is universal.

Taken together, the first three points above argue for option superiority over long stock when the latter trades up a little, sideways, or down.

My fourth piece of evidence is anecdotal study of risk as volatility of returns. I cited studies here and here suggesting that returns are similar between stock and option positions with volatility 33% lower using the latter. Furthermore, my preliminary backtesting has shown lower maximum drawdowns for the naked put positions relative to long stock.

I will continue discussion in the next post.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (2) | PermalinkOptions are Better than Stock (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on September 6, 2016 at 06:09 | Last modified: July 24, 2016 12:22Options folk enjoy debate about things like which trading strategy is best and which adjustment is best. Almost unilaterally when I hear a discussion like this setting up, an immediate answer pops to mind: neither is better or worse—they each have their pros and cons. I feel options are a better vehicle to trade than underlying stock but because of my reluctance to proclaim superiority, I rarely communicate this to others.

In 2014, I made the case for options with a six-part blog series. In Part 1, I wrote:

> I actually believe that trading options is better than

> trading stocks or futures. This would be very, very

> difficult to prove, though. When it gets down to the

> trading system, whether discretionary or systematic,

> it would be extremely difficult to convince anyone

> that options are unequivocally better.

For this reason I took a defensive posture with option trading. I suggested the financial industry represents option trading as making a “deal with the devil.” I then attempted to inject reasonable doubt to weaken that claim. I explained why options are not “too risky” and I went on to offer some advantages of trading options.

In this blog series, I am taking a more aggressive approach: options are a superior investment/trading vehicle to stock. I will make the argument with covered calls/naked puts, which I have blogged about at length.

Pay close attention because the implications of option superiority are significant and wide-ranging. For starters, it may rarely be in one’s best interest to own long stock shares without a hedge. To the extreme, perhaps the vast majority of the financial industry as we know it (e.g. financial/investment advisers) is completely wrong.

Let’s take this one step at a time.

Categories: Financial Literacy | Comments (0) | PermalinkStatistical Wisdom from CHiP’s

Posted by Mark on September 2, 2016 at 07:04 | Last modified: July 24, 2016 11:58Today I feature a lesson on statistics brought to us courtesy of an episode of CHiP’s. The episode “Bio Rhythms” originally aired February 17, 1979.

This particular conversation took place between officers Frank Poncharello (“Ponch,” played by Erik Estrada) and Sindy Cahill (played by Brianne Leary).

[Ponch] Hey Sindy. Feedback on the bio rhythms,

right? Looks pretty good I guess, huh?

[Cahill] Well it’s much too early to tell, Ponch.

Ask me in a couple of months.

[Ponch] Yeah but you must have enough to tell

if the system works…

[Cahill] Well, most everybody in chronobiology

agrees that we all do have rhythms: cycles.

But we don’t know exactly how it works or how

the date of birth is involved. It’s going to

take me a long time to run a large enough

sample to eliminate coincidence. So for

the moment, nope… I don’t have enough data.

[Ponch] Sindy uh, listen… I’ve got a special

interest. I mean, it does look good. Doesn’t it?

[Cahill] Ponch, “looks good” is not a term we

use in statistical study.

Many times I have heard traders speak with overconfidence about strategies that produced one or two winning trades.

I have also seen many casual traders extremely eager to pounce on any promising idea they hear, read, or see.

Both examples are germane to the conversation between Cahill and Ponch. Small sample sizes are susceptible to the possibility of fluke or, as Officer Cahill stated, coincidence. We therefore know nothing until we get a larger sample size. Heuristic thinking like confirmation bias is notorious for driving action during this phase and quite often, people circumvent the hard work altogether by not insisting upon (or being aware of) proper statistical validation.

Categories: Wisdom | Comments (0) | Permalink