Brokerage Perspective on Freeriding vs. Good Faith Funding Violations

Posted by Mark on May 18, 2021 at 07:20 | Last modified: April 23, 2021 10:37Today I will discuss freeriding and good faith funding violations.

I contacted TD Ameritrade (TDA) about the specific example described at the end of my last post and they said it would not be an issue. I would receive an e-mail over the weekend telling me the shares had been assigned and that I need to take immediate action to cover the position. I am clear provided I do this near the open on Monday morning. If I delay, then TDA has the right to apply discretion on a case-by-case basis. In so doing, they will make every effort to do what’s best for my account value and the brokerage.

Before I explain the brokerage perspective, I want to reference the SEC website with regard to “freeriding.” According to the SEC website, I am allowed to use unsettled funds to make a subsequent transaction in a cash account but I must wait until the initial funds settle before offsetting the subsequent transaction. Failure to do so is called freeriding. Covering the short with $191,000 of unsettled funds (recall that the account previously contained $100,000) is okay but continuing to trade with those funds before the $291,000 settles is not.

Freeriding is a violation of the Federal Reserve Board’s Regulation T, and brokers/dealers must suspend or restrict cash accounts for 90 days as a penalty. This shouldn’t be an issue with margin accounts because the funds may be borrowed until settlement clears. If a cash account is restricted, then securities may only be purchased using settled funds. Equity (option) transactions are settled two (one) business day after the transaction date.

TD Ameritrade makes a distinction between freeriding and a good faith violation. Here is an example of the latter:

- On Monday, I hold ABC stock.

- On Tuesday I sell ABC stock, which will settle on Thursday (two business days later).

- On Wednesday morning, I buy XYZ stock.

- On Wednesday afternoon, I sell XYZ stock for a profit.

My Wednesday morning purchase was done on good faith that the sale of ABC would settle thereby making the funds available. I am in violation because I did not wait for the ABC settlement before selling XYZ stock, which means I never fully paid for XYZ. For this, I would receive an e-mail explaining the violation. If I am in violation three times within 12 months, then my account will be restricted to using only settled funds for 90 days.

TDA regards freeriding as a situation where funds are never in the account. An example of this could involve a failed incoming ACH transfer. While ACH transactions may take up to two business days to settle, TDA makes the funds available immediately for marginable stock above $5 on a listed exchange (not options). Suppose that on the day I open a new account with a $25,000 ACH transfer, I buy $25,000 of QRS stock and sell later that afternoon for a 100% profit. If the $25,000 deposit never goes through, then I have committed a freeriding violation and profits will be seized.

In speaking with TDA, my confusion between freeriding and a good faith violation may be explained by limited margin they grant to retirement accounts. Margin is pledging securities as collateral for a brokerage loan. Accounts given tax-deferred (traditional IRA) or tax-exempt (Roth IRA) status are prohibited from accepting such loans and may lose their favorable tax status for doing so. The limited margin applied here is the ability to use unsettled funds for subsequent trades—not to provide leverage, but rather to prevent trip-ups resulting from specific, temporal oversights.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkPotential Tax Implications and Settlement Issues

Posted by Mark on May 13, 2021 at 06:54 | Last modified: April 23, 2021 10:14Before I go into the second part of this investment approach, I want to address tax considerations and discuss some details about option assignment and settlement.

Please keep in mind the following disclaimer: I am not a tax professional and while the following holds true for me, your personal situation may differ.

If a long-term long call is substituted for the married put, then favorable tax treatment may be available if done with cash-settled SPX options rather than SPY. The underlying index (SPX) cannot be purchased, so the synthetic equivalent must be used in lieu of the married put. I have read—but not confirmed—that some brokerages allow for cross-margining between SPY shares and SPX options. I wonder if said brokerages would cross-margin with other S&P 500 ETFs as well (e.g. IVV)?

Because I am not a tax specialist, I will quickly go over tax implications even though this deserves much more space. Options held longer than one year qualify for long-term capital gains (LTCG) treatment. The SPY ETF qualifies for LTCG treatment if held for more than one year (with the goal being to presumably hold and defer tax payment indefinitely). As suggested above, “favorable” means profit/loss on SPX options gets split into 60% LTCG and 40% short-term capital gains regardless of holding period. Holding for longer than one year would be ill-advised because I would still have to pay 40% short-term capital gains taxes on what would otherwise qualify as 100% LTCG (e.g. SPY options).

Assignment of shares can be a problem for retirement accounts. Consider what happens if I sell 10 Jul 300/290 bear call spreads on SPY for $3.00 each in my $100,000 IRA account. The most I can lose appears to be 10 * $100/contract * 10 contracts = $10,000, which is 10% of the initial account value. At expiration, suppose SPY trades at $291. I will be assigned on the short 290 calls forcing me to sell 1000 shares for $290,000. Because short positions are not allowed in IRAs, the position must be covered immediately. At Monday’s open, suppose I buy to cover for $291/share (assuming no price change from the close, which is not very realistic). I lose $1,000 of the $3,000 initially credited at trade inception on the assignment/cover, bank the profit, and move on.

“Not so fast, my friend.”

Being assigned on the short 290 calls brings 290 * $100/contract * 10 contracts = $290,000 into my account, but trades are not settled until two business days after execution. Being an IRA account, I must cover the short immediately with $291,000, which I do not have currently available since the sale has not yet settled.

Is this a problem?

I will discuss next time.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkNot Exactly a Cash Replacement Strategy (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on May 10, 2021 at 07:06 | Last modified: April 20, 2021 09:49Today I continue study of what I am calling not exactly a cash-replacement strategy: the first component of a new (to me) investing approach.

This component is not exactly a cash-replacement strategy because it carries more risk than cash, which can really only lose to inflation. Backtesting will help to put context around “more risk,” but max loss being realized over a string of consecutive years would severely damage core equity. If I deem the potential for adverse performance to be limited, then I may choose to use this as a cash replacement.

I can think of a few potential variants with the first being leveraging up leftover cash. In the example I gave last time, on a $247 investment my max risk is less than $20 (not counting dividends) for the year. Why not double to 200 shares and buy two puts? My max risk would then be less than $40, which is just under 17%, and my potential profit (unlimited) would increase twice as fast. The downside is that losses start to accrue with anything less than a $20 (per 100 shares) gain by expiration.* I am interested to look at the historical distribution of returns to get an idea of the probabilities.

A second potential variant to the married put cash replacement is resetting the long put ATM to lock in gains once the market rallies X%. This would cost more money although if months have passed, then I can seize the opportunity to roll the put out in time, which would eventually have to be done anyway.* I think backtesting this entire approach will have to be some sort of horizontal (by date) summation of components. For this variant, separate backtesting of the put involves exit after an X% gain in the underlying (for a loss) or exit with Y months to expiration (for a gain or loss): whichever comes first.

A third variant to the married put cash replacement is to buy a put debit spread for limited downside protection if VIX > Z. This would limit cost of insurance at the risk of losing more overall if the market decline continues thereby forcing an early exit (e.g. at the long strike?). From a backtesting perspective, this would be challenging because not only do I have to backtest across a range of Z, I should also backtest across a range of vertical spread widths (or debit spread prices).

A married put is synthetically equivalent to a long call, which suggests as a fourth variant purchase of a long-dated ATM call alone. With one leg instead of two, this might be an easier trade (unless I were to hold SPY shares and only move around the long put, which would nullify the simplicity advantage). Done this way, I should invest the remainder in T-bills or some other cash proxy unless I intend to leverage up as described three paragraphs above.

I will continue next time.

* — My intent will not be to hold to expiration due to accelerated time decay in the final months.

Not Exactly a Cash Replacement Strategy (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on May 7, 2021 at 06:53 | Last modified: April 19, 2021 17:18Today I will talk about the first component to a hedged approach to option trading.

A cash replacement is relatively safe. Cash is savings accounts, money market accounts, certificates of deposit, FDIC insured, etc. Cash suffers from inflation risk: it will be devalued over time if the interest rate (currently near zero) is less than the rate of inflation, which is generally not the case (see below). A cash replacement will not be government insured, but it should have comparable risk in terms of how much it may lose in any given year.

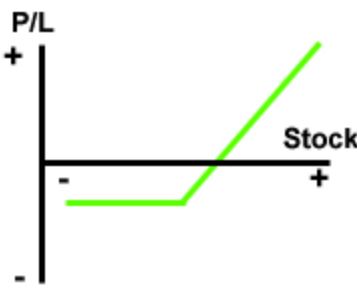

The first component in the proposed hedged portfolio approach is a married put. This is a long-term ATM put and 100 shares of underlying stock. The maximum potential loss is the total cost of the put. If the market is lower at expiration, then the loss incurred by the shares is offset by intrinsic value of the long put. If the market is higher at expiration, then the cost of the put subtracts from gains in the shares. The risk graph is shown below:

Before I can assess a potential cash replacement, I need to understand the historical annualized return on cash. According to Portfolio Visualizer, using Vanguard Short-Term Treasury Fund Investor Shares (VFISX) as a proxy for cash reveals an average CAGR of 3.75% (1.48% after inflation) from Jan 1992 through Mar 2021. The range is -0.57% to 12.11% with a standard deviation of 1.91%.*

Next, I need to run a backtest to get a comparable performance distribution for the married put. The shares will benefit from the annual dividend to discount the put cost, which is ~2% in recent decades.

Always implied when we see benchmark returns is that 100% of the account is invested. Few people really do that. The long-time rule of thumb, which I am not advocating, has been to invest in equities a percentage equal to “100 minus your age.” In a pinch, a “conservative” asset allocation often preached is 60% stocks + 40% bonds. Either way, whatever the equities return in any given period must be diluted accordingly to calculate total portfolio return.

If I believe the married put to be sufficiently safe, then I can use it as a repository for cash in the account and avoid deleveraging the portfolio as just described. Committing 100% of my investible assets to an approach like this would immediately give me a 4% (or more) advantage per 10% CAGR according to the traditional approaches mentioned above. That’s a huge head start.

While I will be interested to see the overall return of the married put, in theory the total cost seems more reasonable in periods of low volatility than high. In the latter portion of 2017 with SPY around $247, a 2-year ATM put could be purchased for about $20. The dividend yield was about 2% so the annual cost of this insurance was about 2.1% (rounding up).

Would I risk putting my remaining assets in a vehicle that could lose no more than 2.1%? Inflation has averaged 1.2% over the last 12 months, which means cash has returned roughly -1.0%. Losing 1% is not much better than losing 2.1%, perhaps, although with implied volatility currently higher maybe the potential loss is also higher—either way, if my answer is ultimately yes then this could adequately serve the purpose of cash replacement.

I will continue next time.

* — As an aside, correlation to US equities is -0.19.

The Road Forward

Posted by Mark on May 4, 2021 at 07:20 | Last modified: April 19, 2021 08:33I am at an inflection point. Time to take a step back, review where I’ve been, and more clearly define where I am going.

I haven’t been happy with my downside risk after 2018 when, for all practical purposes, I lost money for the first year since switching to full-time trading in 2008.

Initially, I thought the way around this was migration to a portfolio of diversified asset classes. I found Following the Trend by Andreas Clenow (2013) to be quite the eye-opener.

I then thought I should learn some Python to backtest some noncorrelated futures markets to validate Clenow’s book (especially because of this comment).

In between, I took a course on algorithmic trading and spent several months trying to develop my own trading system. Some of this time included use of a genetic algorithm. Although the total number of strategies I tested amounts to a proverbial “drop in the bucket,” none of this worked.

I spent a minute trying to build a futures backtester in Python. I wasn’t encouraged by the speed of my program and I wasn’t sure how to proceed coding the trading rules. Although I did not expend great effort in searching, I was not able to find a project collaborator.

Late February through March 10, 2021, I contemplated preparation for CFA Level I. I had several contacts with the CFA Institute and board members of the local CFA societies. As it turns out, my trading experience does not qualify me for CFA Charter because I haven’t been working in the industry proper. I could still take (and hopefully pass) the exams, but in order to become an official charterholder I would have to work 4,000 hours over at least three years at a financial firm.

Because of the low pass rates, I believe passing the exams would get me in the door with many prospective employers. Even without the charter, anyone who talks to me about what I have been doing since 2008 will quickly find out that I have learned a great deal about trading and investing over the 13+ years (regardless of how well I have performed doing it, which is another discussion altogether).

I decided not to begin preparation for the CFA exam and since making that decision, I have caught up on my 18-month backlog of financial publications.

Most recently, I have done some intense reading and studying of the writings of KR: an online investment contributor. This individual has been very generous writing many articles and answering questions about his approach, which hedges downside risk, for free. His is really a compilation of trading strategies that would best be served by backtesting each strategy independently and, if I could nail down allocation for each component, computing a weighted average of % PnL by date. This assumes I can get daily performance exported to .csv, which is not a trivial matter. The backtester I’d like to try for $39/month cannot do this.

Over the next few posts, I will start slow by discussing some of KR’s content.

Categories: About Me | Comments (0) | PermalinkAn Insider’s View on Jobs in the Financial Industry (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on April 29, 2021 at 07:19 | Last modified: March 15, 2021 15:21Today I will conclude discussion of a phone call I recently had with my brokerage rep about jobs in the financial industry.

If I insist on sticking with options, my rep said I would have trouble finding a place with large, established firms because most do not deal in options due to their risky perception among the general public (I disagree as discussed in this mini-series).

Logistics may be another issue with option trading. One transaction with stock, ETF, or fund proceeds can be easily distributed across multiple accounts. This would be more difficult with options. Since client suitability varies drastically, I probably would not have proportional positions across the different accounts. Such accounts would therefore require more individual attention: a slight tweak here or a larger hedge there to balance different accounts. In effect, I would have to go from one client account to another until I were through them all—and heaven help me when Mr. Market decides to make a sudden, large move against the overall position as I would hardly get the chance to adjust in a timely manner.

Whether starting with a more established firm or opening my own RIA, finding clients would be a challenge. Working for the brokerage, my rep gets leads every day from investors opening new accounts. Nobody is calling an Edward Jones or Raymond James wanting to open a new account, though; people calling firms like these are looking specifically for advisory services, which makes getting clients more difficult. This dovetails with a 2019 survey that reveals very few Americans actually have financial advisors.

He also mentioned that 95-97% of new RIAs fail in the first year or two. We didn’t discuss cost to start one, but the low probability of success provides plenty of reason to tread lightly (or not at all).

The rep talked a bit about his own background. He worked for a bank where he sold a $1M annuity in January of the early 2000s. This was about 5x more than the average monthly revenue for the entire investment advisory department. When the following January rolled around, his target was 10% more than what he took in the previous January: $1.1M. This was an outlandish expectation that put him under a great deal of pressure.

I certainly don’t want that.

Near the end of the call, I expressed my skepticism of algorithmic trading profits. I brought up “equity trading revenue” (with regard to Goldman Sachs) and he replied with “underwriting profits” and said this could be the result of positions held in a company for whom they are doing the underwriting. These are not profits generated from algorithmic trading at all, as people often surmise, and would support my thesis about how difficult it really is to develop algorithmic trading strategies that work.

Categories: About Me | Comments (0) | PermalinkAn Insider’s View on Jobs in the Financial Industry (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on April 26, 2021 at 07:33 | Last modified: March 15, 2021 14:34My primary brokerage has a toll-free number I can always call and a general e-mail to support. They were nice enough to provide me with a local personal contact in case I ever have issues to discuss with a familiar voice, as well. Back in January, I had an informative phone call with my representative about working in the financial industry.

I prefaced the discussion by telling him that I have been trading my personal account full-time for over 12 years and am very thankful things have worked out thus far. Since I have successfully navigated my own account, I would like to do the same for others. How might I make this transition?

My expertise is in trading and strategy development. I think of myself like a quant but not as sharp as the professionals because I haven’t had as much [recent] math, statistics, and/or programming coursework. I would like to at least think I know my way around making money in the trading space. This has been true for the better part of 13 years [and could end at any point, which is why I don’t really like to talk about it much as noted in the second paragraph here]. Most everyone with whom I have shared my career story has been impressed with what I have done.

I asked how the suitability standard for investment advisors compares with option trading clearance for brokerage clients:

- Tier 1: covered calls and cash-secured puts

- Tier 2: Tier 1 trades and outright long options

- Tier 3: Tier 2 trades and vertical spreads

- Tier 4: Tier 3 trades, uncovered spreads, and naked short options

I think Schwab has three levels, but this four-tiered structure is currently in force at E*Trade. To get full option trading clearance, one needs to claim extensive knowledge, trading experience, and sufficient liquid net worth. The option application asks about investment goals (e.g. why are you investing in options?) but nothing about investment time frame. A suitability assessment will ask about time frame but nothing about investment experience.

If I want to continue managing my own accounts, my rep said most financial firms would require I move the accounts over to them (or their custodians) and would not allow me to trade during the business day. The latter makes sense since I’m being paid to work for them. Moving accounts over, though, might come at a cost of being able to trade options altogether depending on their custodian, clearing firm, and/or available permissions. This may or may not be a compliance issue.

I would never want to give up self-directed trading, which is my primary source of income. So much for working as an investment advisor for an established firm?

I am worthy of self-promotion (see here and here) but still missing the piece about how to get from here to there.

I will continue next time.

Categories: About Me | Comments (0) | PermalinkDoes Technical Analysis Work? Here’s Proof! (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on April 15, 2021 at 07:10 | Last modified: March 11, 2021 12:01Today I continue with commentary and analysis of Janny Kul’s TDS article with the same title.

I was a bit confused where we left off. Kul continues:

> It appears as though there may be Alpha reversing filtered technical

> indicators… We’d need to keeping [sic] rolling this forwards to

> actually find if this relationship continually holds.

I think he’s basically suggesting we test the worst performers from the training set for outperformance. That is a very interesting idea. I would want to know if the worst training indicators do better on the test set than the best training indicators. This reminds me of the Callan Periodic Table of Investment Returns, which I mentioned in the middle of this post.

> Obviously adding transaction costs and bid/offer would mean we can’t…

> capture this but this does give us something to investigate further.

Does he mean we can’t realize any profits from this or just diminished profits? He could have included sample transaction fees to get more clarity on this.*

He then teleports ahead to Bitcoin. Say whaaaaaat? Speaking of transaction fees, though, exactly what vehicle is being used to trade it and what are the usual slippage and commissions to do that? I (and most veteran investors, probably) would be very interested to know since Bitcoin is relatively new.

> So our train period has a monthly average of 20.4% and our test period

> has annualised returns of 14.3%…it appears as though there may be

> some Alpha on all technical indicators for Bitcoin.

That sounds encouraging…

> Interestingly in our train period we outperform Bitcoin but in the test

> period Bitcoin outperforms.

If buy-and-hold outperforms, then the indicators have no alpha. Why did he just say otherwise?

> In order to say with certainty if this relationship holds we’d again

> need to test again over a longer period of time.

Kul then repeats the backtest for all 12 months of 2018. This extends the backtest by five months since the first six months were the training set and July was the testing set.

> I think it’s fairly safe to say that the performance of all the

> indicators decays over time however we do actually outperform

> buying and holding Bitcoin (although, granted, 2018 was a terrible

> year for Bitcoin).

I think it’s fairly safe to say we really can’t make any conclusions over such a short period of time where the results are so inconsistent with what we saw before.

Kul concludes:

> We found… reversing filtered indicators may have Alpha for non-

> Bitcoin instruments and for Bitcoin… our regular indicators

> may have… Alpha although it does severely decay over time.

Indicator performance declined over the course of these several months, which is still a short time interval. I wouldn’t generalize to “over time,” which sounds much more substantial.

> We’d need to test on a much larger data set to see if these

> relationships do actually hold.

Kul catches himself here and I totally agree. Indeed, the biggest critique I have of this article is the limited backtesting interval. Although he uses a 5-minute time frame, the total study period is one year or less. In case we are looking at a large sample size, Kul could have boosted credibility by reporting number of trades in each group, which he never mentions.

In the final analysis, I can’t help but respond to Kul’s title with “Where’s the beef?”

I will continue next time.

* — I feel strongly about including transaction fees in backtesting as discussed in paragraphs 2-3 here.