Investing in T-bills (Part 9)

Posted by Mark on March 4, 2024 at 10:59 | Last modified: April 1, 2024 10:04The revelation from Part 8 is the hidden cost associated with synthetic long stock (SLS).

To explain this, I now think in terms of an argument that posits edge being arbitraged away once discovered by the masses. T-bills pay annualized interest ~5%: much higher than the default return on cash (currently 0.35% as stated in this second paragraph). This would drive the masses to sell stock, buy calls (or SLS), and invest the capital difference in T-bills. The resultant buying (selling) pressure on calls (puts) would put upward (downward) pressure on call (put) option prices. As seen here, calls end up more expensive than puts.

Nasdaq.com explains this in terms of stock investors who buy on margin:

> When interest rates rise, the cost of borrowing money to buy

> stock on margin increases. For example, if you want to buy

> $10,000 worth of stock on margin, the cost to use margin

> is much higher when interest rates are at 5% vs. 2%.

>

> Therefore, a trader may look to buy a call option to avoid this

> increased margin interest. For this reason, the pricing of call

> options will rise when interest rates are hiked…

>

> The options market reacts to interest rates, causing call options

> to increase in value. Instead of buying $10,000 worth of stock

> on margin, a trader can purchase a call option to benefit from

> the same upside with much less capital, say $1,500.

>

> The saved $8,500 can be put into a risk-free asset such as a

> T-bill to generate interest, allowing the trader to benefit from

> the potential upside of a stock and generate income with a bond.

>

> Due to the traders’ ability to generate a risk-free return on this

> saved capital, the price of call options increases. There is no

> free lunch in the stock market, so when opportunities like this

> arise, it will reflect in the price of call options.

Investopedia explains the decreased put premiums as follows:

> Theoretically, shorting a stock with an aim to benefit from a price

> decline will bring in cash to the short seller. Buying a put has a

> similar benefit from price declines, but comes at a cost as the put

> option premium is to be paid. This case has two different

> scenarios: cash received by shorting a stock can earn interest

> for the trader, while cash spent in buying puts is interest

> payable (assuming the trader is borrowing money to buy puts).

>

> With an increase in interest rates, shorting stock becomes more

> profitable than buying puts, as the former generates income

> and the latter does the opposite. Thus, put option prices are

> impacted negatively* by increasing interest rates.

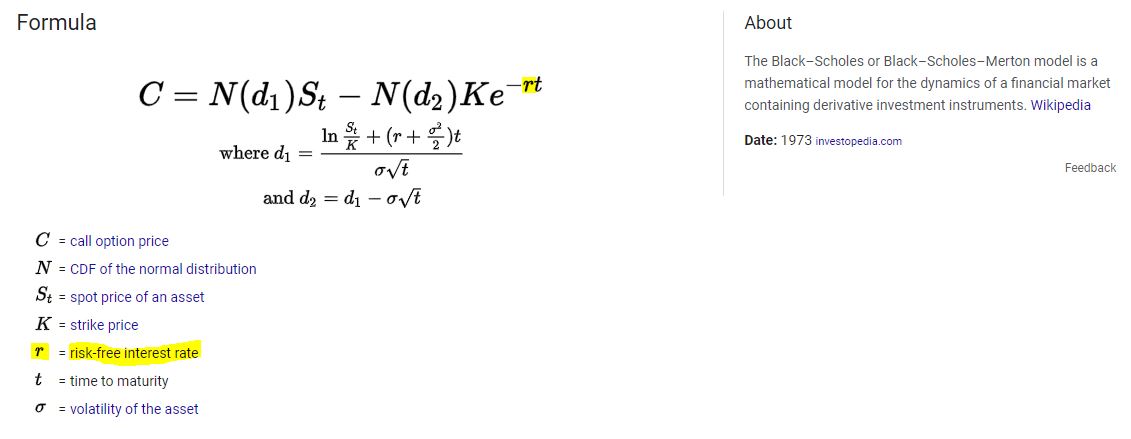

Interest rates are actually part of the Black-Scholes model of option pricing. Again, per Investopedia:

This shows call pricing as a function of two complex terms. The second term is subtracted and interest rates (greek letter rho highlighted in yellow) are in the denominator of this second term. As interest rates increase, the denominator increases thereby reducing the second term leaving—since less ends up being subtracted—a higher call price.

I will continue next time.

* — Lower demand can negatively impact put prices.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkInvesting in T-bills (Part 8)

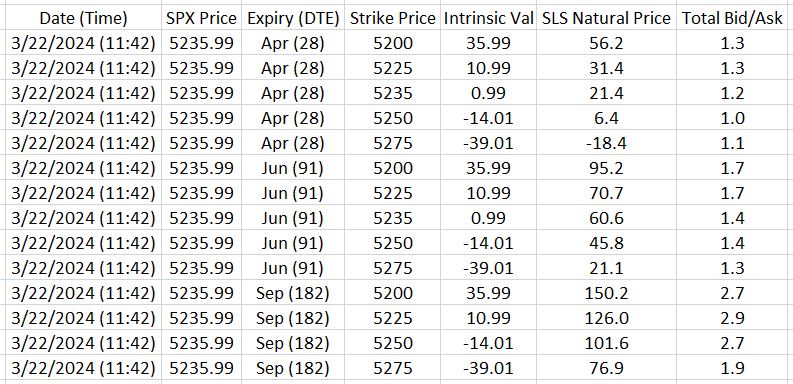

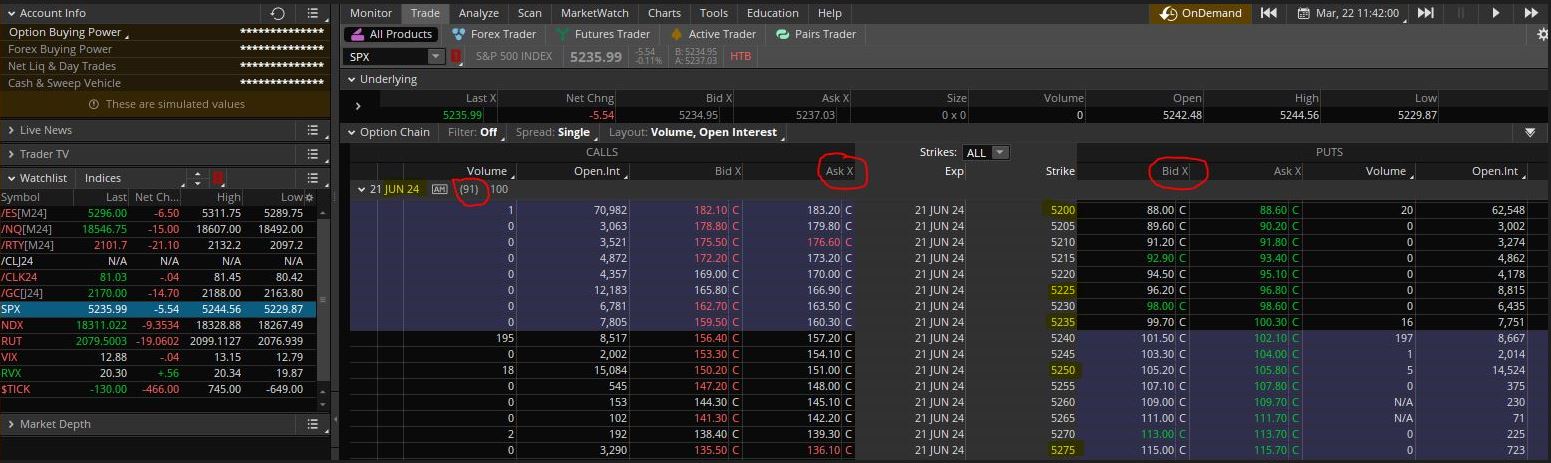

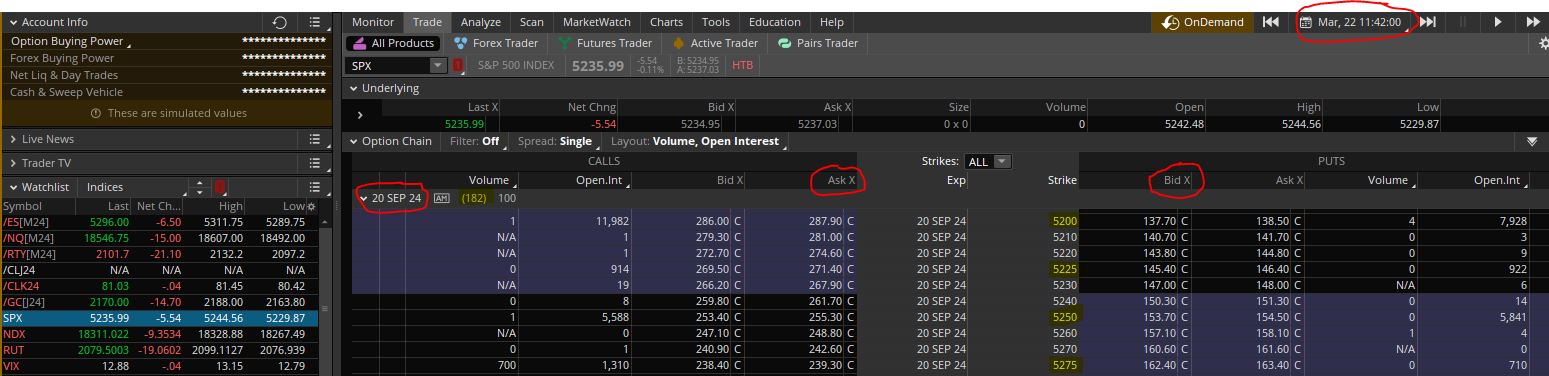

Posted by Mark on March 1, 2024 at 11:41 | Last modified: March 28, 2024 13:54The last table in Part 7 shows pricing data for synthetic long stock (SLS) positions in SPX: a combination of different expirations and strike prices. This brings me to a shocking revelation.

Walking the chain reveals loss from holding the SLS position. This means looking forward in time to get an idea what pricing will be like if “all else remains equal.” 91 days from now, the Sep position—now 182 DTE with a cost of $76.90—will be 91 DTE. Looking at the 91 DTE option chain (hence “walking the chain”) today (Jun expiration) shows the Jun 5275 SLS costs $21.10. 63 days after that, the Sep position would be like today’s Apr position with 28 DTE: established for an $18.40 credit. What I originally purchase for $76.90 will cost me an additional $18.40 to close in 154 days. That represents a loss of $76.90 + $18.40 = $95.30 or $9,530 per contract.

Say what?

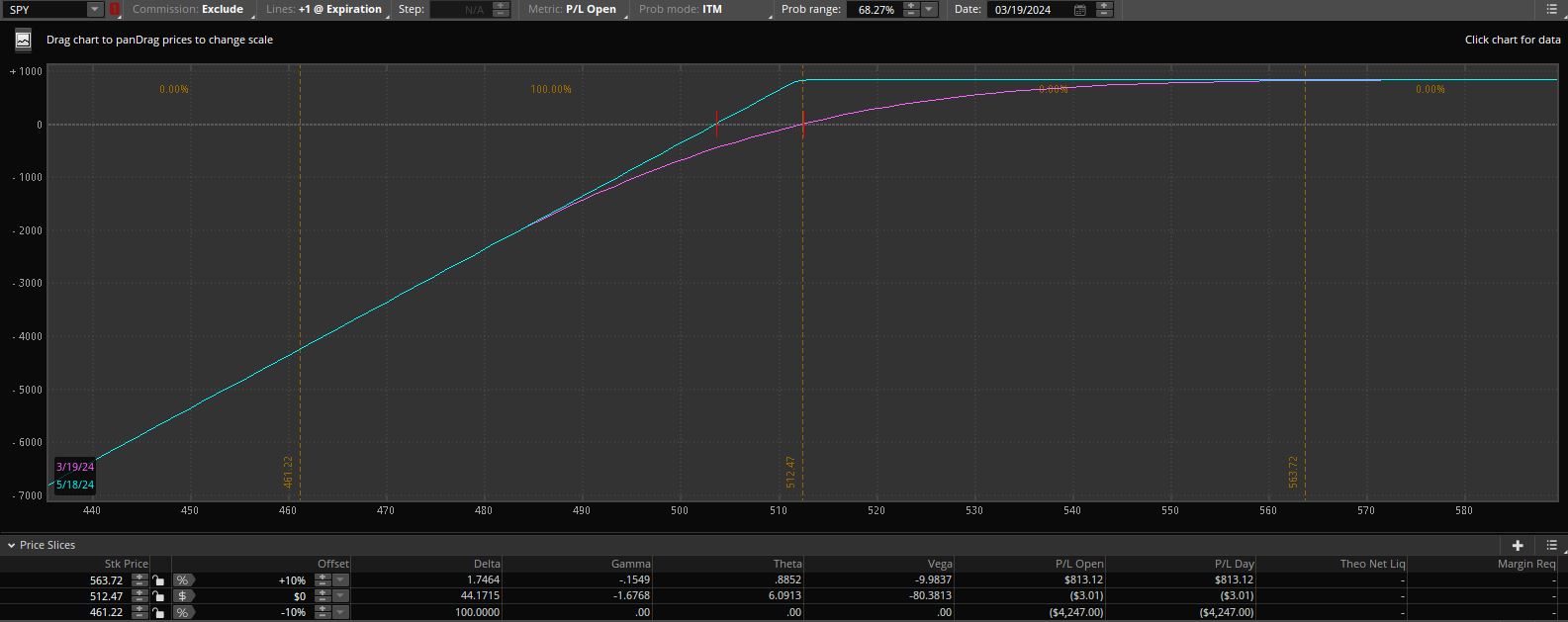

The risk graph provides confirmation:

The purple line on 3/21/24 shows a current PnL of -$219.59. The cyan line on 9/21/24 shows a PnL in 182 days of -$11,609.10. This is a loss of $11,389.53. The SLS saves $523,599 (cost of 100 shares) – $7,690 (cost of SLS) = $515,909 for a [all-else-remains-equal] cost of (11,389.53 / 515,900) * (182 / 365) * 100% = 4.43%/year of the capital saved.

Let’s review.

I have been exploring the idea of trading SLS + T-bills as a way to get equivalent long stock exposure and bond interest.

I just discovered that trading the SLS incurs a cost that offsets much of the interest paid by T-bills.

What we have is another instance [so often heard when studying investing/trading/finance] of “no free lunch.” Also coming to mind is “can’t eat your cake and have it too.”

I had been starting to think trading SLS and investing in T-bills might provide an edge over buying the long stock outright. Rather than a potential edge to be had, I now see it more like a detriment suffered if T-bills are not purchased while holding the SLS. As an option trader with lots of free cash, T-bills must be purchased to avoid missing out on what is basically free money. As a more traditional equity investor, while T-bills still appear to be the better deal (by roughly 0.47%), I’m not convinced going the SLS route is worth doing given the remaining considerations when comparing the two.

I’d be lying if I denied any presence of sour grapes right now. The Options Playbook says:

> For… [SLS], time decay is somewhat neutral. It will erode the value of the option

> you bought (bad) but it will also erode the value of the option you sold (good).

Nothing could be farther from the truth in today’s environment.

I will continue next time exploring why this might be.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkInvesting in T-bills (Part 7)

Posted by Mark on February 27, 2024 at 10:26 | Last modified: March 25, 2024 15:04Before continuing to compare stock investing (S&P 500 ETFs and mutual funds, in particular) with synthetic long stock / T-bills, I have some other loose ends to tie up.

Let’s detail the first footnote from Part 4:

> The call is more expensive than the put because it includes over

> $2.00 intrinsic value. This is touched upon in the third paragraph

> here,but I would refer you to an introductory book/article on options

> for a more complete explanation. For at-the-money equity

> options, puts [premiums] are generally more expensive than calls.

The Options Playbook echoes this:

> If the stock price is above strike A, the long call will usually cost

> more than the short put. So the strategy will be established for a

> net debit. If the stock price is below strike A, you will usually

> receive more for the short put than you pay for the long call so

> the strategy will be established for a net credit. Remember: the

> net debit paid or net credit received to establish this strategy will

> be affected by where the stock price is relative to the strike price.

As I write in this sixth paragraph:

> Lots of ideas from financial professionals and investment gurus

> sound good, but I believe the only way to understand what has

> truly worked is to analyze the data.

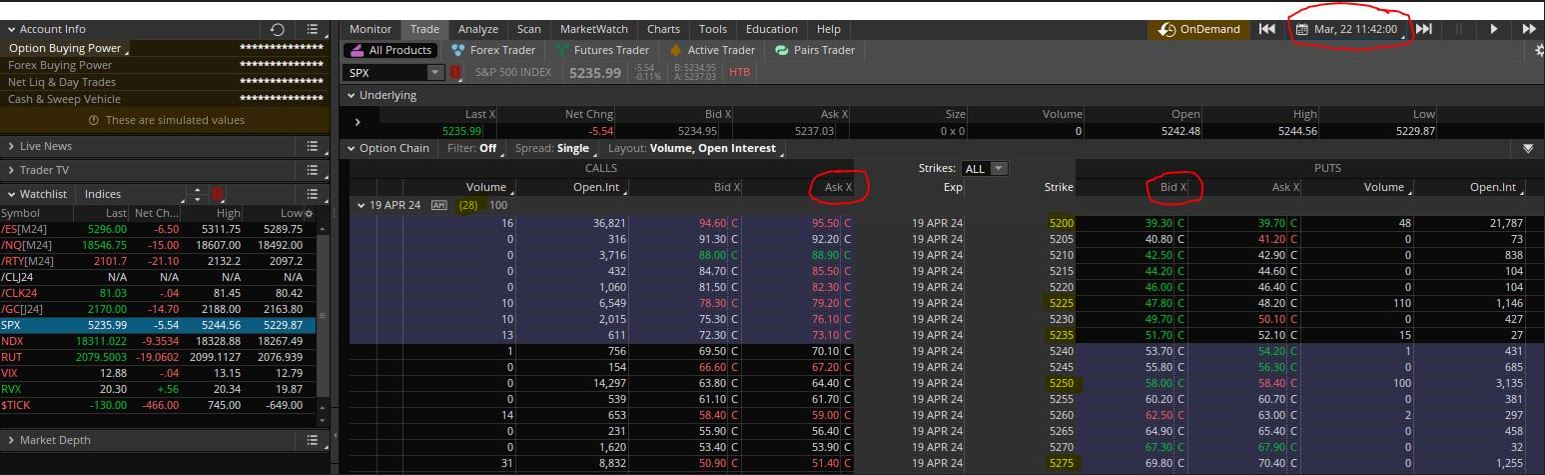

Let’s turn to some data in the form of option chains from three different expirations:

Extracting data from the circled columns, date, and highlighted strikes:

“SLS [Synthetic Long Stock] Natural Price” is the call [ask] premium minus put [bid] premium.

“Total bid/ask” is the sum of the ask premium minus bid premium for both call and put.

Although intrinsic value (strike price minus underlying price for puts and underlying price minus strike price for calls) is nonnegative, I have used a positive (purchase) and negative (sale) sign for calls and puts, respectively, in the “Intrinsic Val” column. This facilitates evaluation of the hypothesis that intrinsic value in calls (puts) makes SLS price higher (lower).

SLS price does indeed go down as intrinsic value shifts toward the puts.

In only one instance out of 14 is SLS price negative, however. I expected SLS of equal and opposite moneyness to have equal and opposite price (as Options Playbook implies above). A closer look at the option chains reveals calls in these near-the-money strikes to be more expensive than puts. This runs contrary to traditional wisdom about vertical skew ever since Black Monday (1987) and demands further research.

But wait: there’s more!

Next time I will continue with the most shocking revelation of all.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkInvesting in T-bills (Part 6)

Posted by Mark on February 22, 2024 at 13:24 | Last modified: March 24, 2024 08:57Today, I continue addressing the first consideration when comparing stock investing (S&P 500 ETFs and mutual funds, in particular) with synthetic long stock / T-bills.

As mentioned in the second-to-last paragraph of Part 5, synthetic long stock requires advanced trading permissions from the broker [score one point for stock investing]. I think this is mainly due to a need for close monitoring as expiration approaches and knowledge required about proper management depending on whether the underlying has gone up or down.

If the underlying (ETF) has increased through expiration,* the long call must be sold [thereby incurring slippage, commission, and exchange fees—score another point for stock investing] because automatic exercise will occur if in-the-money (ITM) by at least $0.01. This cannot be allowed to happen because avoiding stock purchase is precisely why the synthetic is being traded in the first place. The short put can probably be left to expire with close monitoring for sudden downside movement if the ETF is trading anywhere near the stock price** in order to prevent what I will describe next.

If the underlying has decreased through expiration,* the short put must be bought (to close) [again incurring slippage, commission, and exchange fees]. The short put may be assigned early if it goes deep ITM or assigned at/near expiration if it is even slightly ITM. Extrinsic value is something to be monitored; if this shrinks to a penny or two,*** then immediate closing (rolling) is prudent. Any extrinsic value in the long call could be salvaged by a sale. In fact, for the synthetic long stock to perfectly mimic gain/loss of the underlying shares, both options should be closed together and concomitantly replaced with a later-dated position.****

I have at least two ideas to significantly limit assignment risk. First, avoid expiration week altogether by rolling synthetic long stock no later than 7 DTE. Especially if positions are established far from expiration, the difference between rolling at 7 DTE vs. expiration week proper is trifling. Second, trade the synthetic with SPX options rather than SPY. Any assignment of SPX options results in a cash credit/debit for the difference between strike price and underlying [SPX index] price rather than an obligation to buy the full 100 shares of SPY [multiplied by number of contracts].

I will continue next time with a brief discussion of option liquidity for S&P 500 ETFs.

* — Assuming an at-the-money synthetic stock position at inception, which need not be the case.

** — This applies more to PM-settled options that can be monitored right up to expiration. Closing

AM-settled by 4:15 PM ET (check option specifications for exact trading hours) is prudent

when trading within a couple (few?) standard deviations of the strike price to limit chances

of a big overnight move resulting in assignment.

*** — $0.05 – $0.10 for SPX options

**** — “Concomitantly” makes this a theoretical impossibility but opening a new synthetic long

stock position ASAP after closing the existing is sufficient.

Investing in T-bills (Part 5)

Posted by Mark on February 20, 2024 at 11:37 | Last modified: March 20, 2024 21:37Having now completed the comparison between long calls and short puts, we’re now ready to consider both at once.

A long call and short put opened at the same strike price produce a risk graph that may look familiar:

This is known as synthetic long stock. One contract of each option will be virtually identical to 100 shares of the underlying stock (SPY ETF in this example) with regard to profit/loss.

Here are the vitals:

- The cost to open this position is $14.14 – $8.31 = $5.83/contract (or $583 compared to $51,220 to buy the stock).

- The purple (cyan) curve shows profit and loss today (in 59 days at May expiration) based on a range of prices for SPY.

- Like stock, this has unlimited profit potential and maximum loss to be realized if SPY goes to zero at expiration.

For purposes of T-bill investment, the cost savings is paramount: $51,220 – $583 = $50,637 saved via synthetic stock can buy T-bills for a guaranteed [by the full faith and credit of the United States government] return of [currently] over 5.0% per year.

This blog mini-series has led to exploration of synthetic long stock as a higher-performance alternative to stock shares. Most people who invest in mutual funds or ETFs are committing the full $51,220 mentioned above without any T-bill exposure. What about trading options for a fraction of the cost and getting 5%/year on the difference?

I can’t find any supporting statistics, but I would venture to say investment in S&P 500 index mutual funds and/or S&P 500 ETFs are the most popular equity investments in existence (coming in a close second may be total stock market funds/ETFs). S&P 500 vehicles are offered in every retirement plan I have ever seen, heard of, or read about. Most articles I study in financial journals use these index mutual funds or ETFs (e.g. SPY, IVV, VOO) as a proxy for equity investment performance. They also have among the lowest expense ratios and narrowest bid/ask spreads of any issues traded on Earth.

The first of several considerations to be made when comparing long stock to synthetic long stock / T-bills is option trading permissions. Option trading levels range from beginner to advanced and different brokers have different categories. TD Ameritrade has three “tiers” while Interactive Brokers has four levels of “option trading permissions.” Most novice traders and IRA accounts receive basic authorization that enables use of covered calls and long call or put contracts. This requires some basic options knowledge and a cash or IRA account with enough funding. More advanced authorization usually requires a margin account. Since the broker risks losing money by lending funds, these levels require some options trading experience and sufficient funds or assets in the account to cover any losses.

The short put places synthetic long stock into a more advanced option trading category. Not being applicable to everyone is a disadvantage because it would therefore require added cost for an authorized trader (investment advisor) to manage.

I will continue next time.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkInvesting in T-bills (Part 4)

Posted by Mark on February 16, 2024 at 10:18 | Last modified: March 19, 2024 12:14I discussed put selling (also known as “short puts” or “naked puts”) last time as a way to participate in underlying stock appreciation in combination with T-bill investing. Before moving forward, I want to tie up some loose ends and present a different way of visualizing previous concepts.

Risk graphs are a way of visualizing potential risk and reward of option positions. I compared and contrasted such details for long calls and short puts in Part 3.

Here is the risk graph for a long call:

- This call is purchased for $14.14/share (the default multiplier for equity options is 100 shares per contract so buying one of these actually costs $14.14 * 100 = $1,414) with SPY [stock, or more precisely ETF] at $512.20/share (early morning on 3/19/24; see second-to-last paragraph here if the dates really confuse you).

- The purple (cyan) curve shows profit and loss today (in 59 days at May expiration) based on a range of prices for SPY.

- Note how the purple curve will sink down to the cyan over time. This represents the premium paid for the call and how some of that premium may be recovered by selling to close prior to expiration (total premium is reflected in the value of the cyan curve to the left: -$1,414).

- Note the unlimited profit potential as the curves have positive slope to the right.

Here is the risk graph for a short put:

- This put is sold for $8.31/share ($831/contract) with SPY at $512.40/share (early morning on 3/19/24).*

- The purple (cyan) curve shows profit and loss today (in 59 days at May expiration) based on a range of prices for SPY.

- Note how the purple curve rises to the cyan over time. This represents the premium received for the put and how some of that premium must be surrendered when buying to close prior to expiration (total premium is reflected in the value of the cyan curve to the right: +$831).

- Note the unlimited [technically limited by SPY reaching zero because stock prices cannot go negative] loss potential as the curves have negative slope to the left.**

Buying calls depletes whereas selling puts raises cash that may be used to invest in T-bills. If the calls become profitable, however, then selling them will increase cash balance whereas closing a short put (or letting it expire) after the underlying stock has decreased can lower cash balance (more on this later).

I will continue next time.

* — The call is more expensive than the put because it includes over $2.00 intrinsic value. This is touched upon in

the third paragraph here, but I would refer you to an introductory book/article on options for a more complete

explanation. For at-the-money equity options, puts [premium] are generally more expensive than calls.

** — One naked put carries less risk than 100 shares of stock because its maximal loss is offset by the premium

received for selling it. This is discussed in further depth here.

Investing in T-bills (Part 3)

Posted by Mark on February 13, 2024 at 11:09 | Last modified: March 18, 2024 16:33In Part 2, I wrote about investing in T-bills while buying calls (also known as “long calls”) in the same account. Today, I will review that discussion and introduce put selling (also known as “short puts” or “naked puts”).

Long calls generally increase in value with the underlying stock once the increase is enough to offset the initial premium previously described as “rent.” In that example from the sixth paragraph here), I pay $13.73/share premium to buy the calls. After 62 days, my position will be profitable if SPY stock [an ETF] has gone up more than $13.73/share and no limit exists to how profitable these may be (net the initial $13.73 premium). If SPY increases less than $13.73/share, my position loses money. If SPY does not increase at all after 62 days, then my whole investment is lost (albeit only 2.7% of the cost to buy 200 shares outright).

I can only buy as many calls as the free cash in my account will allow (self-imposed guideline: I never want to borrow brokerage funds and owe upwards of 13% interest). Buying calls decreases free cash that may be used for T-bill investing.

Aside from buying calls, another way to participate in the movement of underlying stock is to sell puts. Long (bought) puts generally gain value as the underlying stock falls and sold (short) puts generally gain value as the underlying stock rallies. Selling puts allows me to collect premium rather than paying it; this provides a margin of safety if the underlying stock falls.

As an example, rather than buying the calls previously discussed, suppose I collect the $13.73/share premium by selling the corresponding puts.

The story is now different in several ways:

- First, the premium received for put sales (vs. premium due for call purchase) increases the cash balance in my account that I can use to buy T-bills.

- Second, if SPY increases over 62 days, then I keep the $13.73/share profit (vs. having to overcome any premium paid for profitability).

- Third, $13.73/share is my maximum potential profit (vs. unlimited profit potential net premium paid for long calls).

- Fourth, if SPY decreases up to $13.73/share, then I will have to surrender up to the entire premium received after 62 days. A net loss results if SPY decreases more than $13.73 (vs. long calls that incur maximum loss if SPY goes down at all). Potential loss on the short put is nearly unlimited except for the $13.73/share premium initially received.

I will continue next time.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkInvesting in T-bills (Part 2)

Posted by Mark on February 8, 2024 at 06:56 | Last modified: March 16, 2024 12:02Last time I presented Investopedia information on the basics of T-bills: what they are, how they work, etc. Today I’m going to start discussing why to consider investing in them.

I invest in T-bills to get a better interest rate on cash than I otherwise would. I tend to have free cash in my brokerage account. The brokerage currently pays 0.35% interest on that cash. According to the Bankrate website, the national average yield for savings accounts is 0.57%. T-bills are currently paying over 5.0% interest.

Borrowing brokerage money to invest in T-bills would be a losing proposition. Suppose I open a margin account with $100,000 cash. I can buy stock with $100,000 and T-bills with $50,000. I will make 5% interest on the T-bills, but since that $50,000 is borrowed from the brokerage I will have to pay upwards of 13% interest. This is a guaranteed loss of at least (13% – 5%) = 8%. Bad idea… really bad idea.

For those investing in stocks, T-bills may not add much benefit. A stock investor opens a brokerage account to buy stocks. Most of the cash will therefore be deployed to that end. $95,000 may be used to purchase stock in a $100,000 account. This leaves only $5,000 to buy T-bills. It may still be worthwhile to do so, but T-bill investing does carry a minimal time commitment (to be discussed later).

Because options are leveraged instruments, cash outlays are different. Options allow me to control stock for a fraction of the cost. This means more leftover cash that I can conceivably use to purchase T-bills.

Imagine buying calls in the hypothetical account discussed above. With SPY at $509.83/share, I can buy 200 shares of SPY for $101,966. Alternatively, two 510 calls would cost me $2,746. This allows me to effectively rent 200 shares of SPY for 62 days. My position is then worth the difference of SPY and $510 [multiplied by two (options)]. If SPY is less than $510 then my position expires (i.e. “goes out,” “ends up”) worthless. If SPY is at $524, then my position is ~$2,800 (slight gain). If SPY is at $530, then my position is ~$4,000 [a much larger (percentage) gain].

With calls, I take on the risk of losing the full $2,746, but this is only 2.7% of the cost to buy shares. The leftover cash can be used to purchase T-bills. Interest received would be 0.05 * (100,000 – 2,746) * (62 / 365) ~ $849. With shares, because I borrowed $1,966 to establish the full position, I would actually owe 0.13 * 1,966 * (62 / 365 ) ~ $43 . The difference is $892 in about two months.

Interest aside, at the end of those two months the SPY position could also be down $2,746 were SPY to fall $13.73 (to $496.10/share). While this is an equivalent loss to the option position, I retain ownership of the shares and can subsequently recoup the loss if SPY moves higher. Expiring worthless means the option position can never rebound.

I will continue next time.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkInvesting in T-bills (Part 1)

Posted by Mark on February 5, 2024 at 14:37 | Last modified: March 15, 2024 15:36I find an advantage to investing in Treasury Bills, but I am still trying to wrap my brain around how big a benefit this is, to what extent it may be utilized, and/or how much of it is real or just perceived.

Here are some basics courtesy of Investopedia:

> A Treasury bill [T-bill]… is a short-term U.S. government debt obligation

> backed by the Treasury Department with a maturity of one year or less.

> T-bills are usually sold in denominations of $1,000… These securities are

> widely regarded as low-risk and secure investments.

>

> The U.S. government issues T-bills to fund various public projects, such

> as the construction of schools and highways. When an investor purchases

> a T-bill, the U.S. government effectively writes an IOU to the investor.

> Thus, T-bills are considered a safe and conservative investment since the

> U.S. government backs them.

>

> T-bills are generally held until the maturity date. However, some holders

> may wish to cash out before maturity and realize the short-term interest

> gains by reselling the investment in the secondary market.

>

> T-bills can have maturities of just a few days, but the maturities listed by

> the Treasury are are four, eight, 13, 17, 26, and 52 weeks.

>

> T-bills are issued at a discount from the par value (also known as the face

> value) of the bill, meaning the purchase price is less than the face value of

> the bill. So, for example, a $1,000 bill might cost the investor $950.

>

> When the bill matures, the investor is paid the face value—par value—of

> the bill they bought. If the face value amount exceeds the purchase price,

> the difference is the interest earned for the investor.

>

> T-bills do not pay regular interest payments as with a coupon bond, but a

> T-bill does include interest, reflected in the amount it pays when it matures.

>

> The interest income from T-bills is exempt from state and local income

> taxes. However, the interest income is subject to federal income tax.

>

> New issues of T-bills can be purchased at auctions held by the

> government on the TreasuryDirect site. These are priced through a

> bidding process, with bidders ranging from individual investors to

> hedge funds, banks, and primary dealers. These purchasers may then

> sell the bills to other customers in the secondary market…

>

> You can also buy Treasury bills through a bank or a licensed broker

> [i.e. secondary market]. Once completed, the purchase of the T-bill

> serves as a statement from the government that says you are owed

> the money you invested, according to the terms of the bid.

I will get more into the details of investing with T-bills next time.

Categories: Option Trading | Comments (0) | PermalinkYETI Stock Study (10-26-23)

Posted by Mark on February 2, 2024 at 06:45 | Last modified: March 13, 2024 12:09I recently did a stock study on YETI Holdings (YETI) with a closing price of $41.50. Previous studies are here and here.

M* writes:

> YETI Holdings Inc is a designer, marketer, and distributor of premium

> products for the outdoor and recreation market sold under the YETI

> brand. The company offers products including coolers and equipment,

> drinkware, and other accessories. Its trademark products include YETI,

> Tundra, Hopper, YETI TANK, Rambler, Colster, Rambler Colster, Roadie,

> and Wildly Stronger! Keep Ice Longer!, SideKick, FatWall, PermaFrost,

> T-Rex, ColdLock, NeverFail, AnchorPoint, InterLock, BearFoot, Vortex,

> DoubleHaul, LipGrip, Vortex, DryHide, ColdCell, HydroLock, Over-the-

> Nose, and LOAD-AND-LOCK. The company distributes products through

> wholesale channels and through direct-to-consumer, or DTC, channels.

This medium-size company has grown sales and earnings at annualized rates of 32.5% and 19.3% over the last 9 and 7 years, respectively [’13-’14 EPS excluded due to small fractional values that artificially inflate the growth rate]. The visual inspection is mediocre. Sales are up and straight except for spike in ’15 and decline in ’17. YOY EPS are down in ’16, ’17, ’19, and ’22 [I am excluding the latter 57.1% decline due to operational snafus including recall of defective items and inflation-induced demand destruction per Value Line]. PTPM leads peer and industry averages despite generally trending lower from 12.3% (’13) to 7.3% (’22) with a last-5-year mean of 12.3%.

Over the last four years (too brief a history to compare with peer and industry averages), ROE averages 47.6% and is trending lower. Debt-to-Capital is declining since ’16 and falls below peer/industry averages in ’20 with a last-5-year mean of 50.9% [23.8% in ’22].

Interest Coverage is 22.3 and Quick Ratio is 1.0. Value Line gives a “B+” rating for Financial Strength.

With regard to sales growth:

- CNN Business projects 6.3% YOY and 9.0% per year for ’23 and ’22-’24 (based on 16 analysts).

- YF projects YOY 6.6% and 10.6% for ’23 and ’24, respectively (17 analysts).

- Zacks projects YOY 4.3% and 9.9% for ’23 and ’24, respectively (9).

- Value Line projects 9.4% annualized growth from ’22-’27.

- CFRA projects 6.6% YOY and 8.6% per year for ’23 and ’22-’24, respectively (17).

- M* offers a 2-year annualized ACE of 9.8%.

I am forecasting conservatively toward the bottom of the range at 6.0% per year.

With regard to EPS growth:

- CNN Business projects 7.2% YOY contraction and 7.8% growth per year for ’23 and ’22-’24, respectively (based on 16 analysts), along with 5-year annualized growth of 10.4%.

- MarketWatch projects growth of 7.3% and 10.9% per year for ’22-’24 and ’22-’25, respectively (17 analysts).

- Nasdaq.com projects growth of 22.7% YOY and 16.3% per year for ’24 and ’23-’25 [10/10/1 analyst(s) for ’23/’24/’25].

- Seeking Alpha projects 4-year annualized growth of 10.4%.

- YF projects YOY 3.0% contraction and 19.7% growth for ’23 and ’24 (17) along with 5-year annualized growth of 8.6%.

- Zacks projects YOY 3.0% contraction and 18.3% growth for ’23 and ’24 (11) and 5-year annualized growth of 9.4%.

- Value Line projects annualized growth of 12.2% from ’22-’27.

- CFRA projects 2.3% contraction per year and 4.5% growth per year for ’21-’23 and ’21-’24, respectively (16).

I am forecasting below the long-term-estimate range (mean of five: 10.2%) at 8.0% per year. I will not use ’22 EPS of $1.03/share or 2023 Q2 $0.76/share (annualized) as the initial value since those numbers are affected by [temporary] product recall and production issues. Instead, I will start with ’20 EPS ($1.77) and extrapolate to $1.77 * (1.08 ^ 7) = $3.03/share. I can almost ($3.02/share) get to this as a [website] workaround with a 24.0% growth rate projected from ’22 EPS.

My Forecast High P/E is 31.0. With the stock trading publicly since 2018, high P/E has increased from 31.1 to 80.6 in ’22 for a last-5-year mean of 53.0. The last-5-year-mean average P/E is 36.9. I am forecasting below the range.

My Forecast Low P/E is 16.0. Over the past five years, low P/E ranges from 8.6 (perhaps a downside outlier) in ’20 to 27.0 in ’22 with a last-5-year mean of 20.8. I am forecasting below the latter (18.0 in 2018 being the second-lowest value).

My Low Stock Price Forecast (LSPF) of $28.30 is default based on initial value of $1.77/share. This is 32.7% less than the previous close and 3.7% less than the 52-week low.

These inputs land YETI in the BUY zone with a U/D ratio of 3.5. Total Annualized Return (TAR) is 16.9%.

PAR (using Forecast Average—not High—P/E) of 10.6% is less than I seek for a medium-size company. If a healthy margin of safety (MOS) anchors this study, then I can proceed based on TAR instead.

To assess MOS, I start by comparing my inputs with those of Member Sentiment (MS). Based on only 43 studies (my study and 17 outliers excluded) over the past 90 days, averages (lower of mean/median) for projected sales growth, projected EPS growth, Forecast High P/E, and Forecast Low P/E are 10.0%, 13.0%, 35.0, and 17.7, respectively. I am lower across the board. Value Line’s projected average annual P/E of 20.0 is lower than MS (26.4) and lower than mine (23.5).

MS high / low EPS are $1.66 / $0.76 versus my $3.02 / $1.77 (per share). My EPS range is higher, which is quite rare. I think selection of 2023 Q2 as low EPS is unreasonable since results are still being affected by the recall [per Value Line]. I also don’t understand MS high EPS being less than 2020 EPS (7 years earlier). Value Line’s high EPS is $4.20: higher than mine and ~2.5x MS. What doesn’t surprise me is seeing big differences (and questionable ranges) given such a small MS sample size.

MS LSPF of $15.80 implies a Forecast Low P/E of 20.8: greater than the above-stated 17.7. MS LSPF is 17.5% greater than the default $13.28/share * 17.8 = $13.45, which results in more aggressive zoning. MS LSPF is a whopping 44.2% less than mine. I think MS LSPF is unreasonably low: consistent with skepticism expressed in the last paragraph.

My TAR (over 15.0% preferred) is dramatically higher than the 8.4% from MS. I can’t put much faith in MS given the limited sample size of 43. Comparing my inputs with the analyst estimates and P/E ranges as discussed above, I believe MOS to be moderate or better in the current study.

I track a few different [usually conflicting] valuation metrics. PEG is 2.0 and 1.9 per Zacks and my projected P/E, respectively: slightly overvalued. Relative Value [(current P/E) / 5-year-mean average P/E] of 1.5 (M*) is very high, but I believe it to be skewed by a low ’22 EPS caused by nonrecurring events. Kim Butcher’s “quick and dirty DCF” has the stock 40.4% undervalued: 17.0 * [$4.85 – ($0.00 + $0.70)] = $70.55. I’m skeptical of this as well (big discrepancy).

YETI is a BUY under $44. My main source of reluctance is the rocky visual inspection. As additional MOS, I would look to invest at $44 – 10% (arbitrary) = $39.60/share or less.

Categories: BetterInvesting | Comments (0) | Permalink